The great Greenland hunt

All of the muskox calves that eventually came to Norway and Sweden as reintroduction objects originated in East Greenland. So it is there that the return of the Nordic muskox begins.

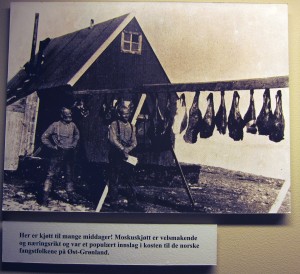

East Greenland first became a Norwegian whaling location then seal hunting grounds in the late 19th century. During the winters on Greenland, hunters and their dogs required food – and the muskox became their favorite prey. According to a hunter’s account quoted in Elisabeth Hone’s The Present Status of the Muskox in Arctic North America and Greenland (1934), sled dogs needed 2 pounds of muskox meet every day, which for a team of 8-12 dogs, meant consuming 20 pounds a day. Such a high demand and the lack of other suitable prey led to a literal muskox slaughter.

Particularly in the 1920s and 1930s, when the rising value of arctic fox pelts encouraged fox farming in East Greenland, the killing of muskox for meat escalated. In addition to muskox feeding the men and dogs, they were also consumed by the foxes. In one 12-month span, an estimated 130 muskox were consumed to support an operation raising 60 foxes. In his comprehensive history Muskoxen and Their Hunters (1999), Peter Lent estimated 12,000 muskox were killed in East Greenland between 1924 and 1939.

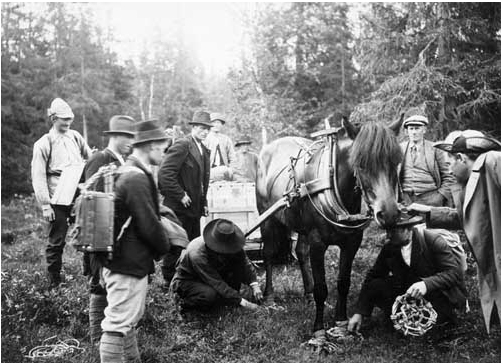

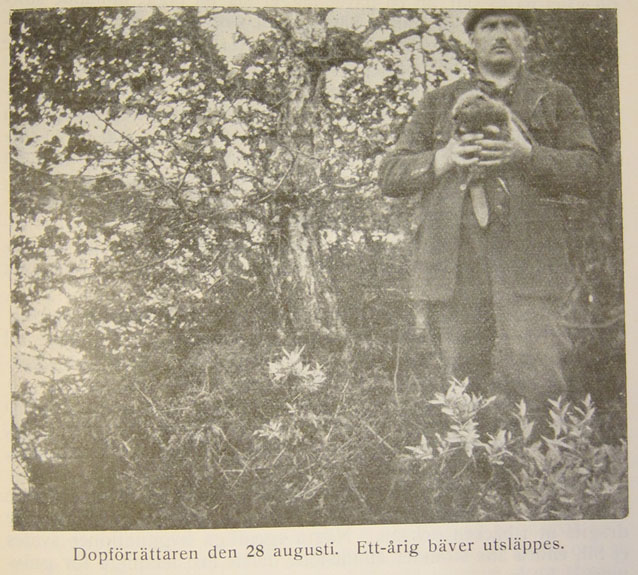

It was within this context that muskox calves were captured alive for translocation. Approximately 350 calves were taken alive from East Greenland prior to 1940, some destined for zoos or private collections and others headed for release in Alaska and Norway (including Svalbard which was claimed by both Norway and Russia). The Norwegian releases included: 10 released on the island of Gurskoy near Ålesund in 1925 & 1926 (all died by 1927); 17 released on Svalbard in 1929 (the last of the Svalbard herd was seen in mid-1980s); and 10 released in 1932 in the Dovre mountains (all died by end of WW2, but more brought afterward and they are still present).

I’d previously asked why these animals were brought to Norway and wrote that the newspaper sources suggested meat was the primary answer. An unpublished manuscript in the Norwegian Polar Institute Library from 1933 by Adolf Hoel, founder of the Norges Svalbard- og Ishavsundersøkelser which became the Norwegian Polar Institute, and the instigator of the muskox reintroduction project, confirms that economic interests — the muskox as meat — played a big role in the project, but it seems keeping muskox as meat in East Greenland rather than having the muskox meat in Norway was paramount:

In recent years people have continuously discussed the best way to preserve the rare species, musk ox, from becoming extinct. In Norway, this query has also aroused great interest both because we are like other cultural people interested in nature conservation and animal protection, and because Norwegians more than other people move and live in the areas in Greenland where musk oxen live.

In Norway it is thus not just for curiosity’s sake that you want to keep it interesting and useful species, but for us Norwegians there is also a major financial interest that a rich population of musk oxen is preserved in Greenland – as large as it can be to utilise the available rangeland. Such a muskox population would not diminish with harvesting for fresh meat along with bear and seal meat for the people living in those areas where the musk ox live. We therefore need to to protect this animal population not only for curiosity’s sake, but also for its economic importance and the enrichment of Greenland’s complete nature and wildlife.

The way to achieve this conservation, according to Hoel, was knowledge, “But if it could happen, but first and foremost acquire knowledge of the muskox’s nature and living conditions in Greenland.” Thus, Hoel actively promoted scientific ventures to East Greenland to study muskox, but in addition, he brought muskox to Svalbard and Norway as other “measures to preserve the musk ox population from extinction.” These reintroduction projects included scientific monitoring and oversight, particularly in the Dovre mountains case in which a zoologist and a veterinarian were charged with monitoring the project. It was indeed a “Norwegian Musk-Ox Experiment,” as John Teal titled an article in 1954.

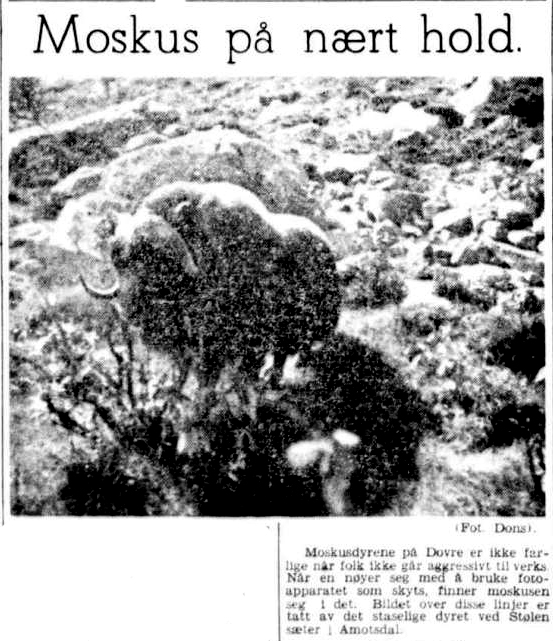

The East Greenland hunt for muskox dominated the thinking about muskox conservation in Norway. To this day, the hunt surrounds the visitor to the Polar Museum in Tromsø, as muskox skulls, skins, and stuffed bodies seem to stand out in every corner. The hunt becomes the mode of telling the muskox’s story, but does that mode make us more or less aware of the muskox’s history? Take a look at some pictures of the muskox in the Polar Museum and see what you think. And compare those with the graphic display of a seal hunt in the same museum, a display which upset my 6-year-old who is peering over the wall in shock that a man would kill a baby seal. Do the muskox become specimens extracted out of time or are they still grounded in the great Greenland hunt?