Controlling transgressors

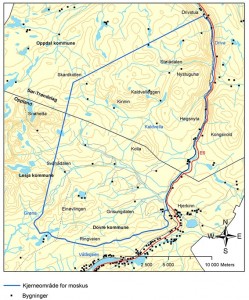

On Sunday, 25 August 2013, the Norwegian wildlife management branch of the country’s environmental agency (Statens naturoppsyn) killed a muskox that had wandered too far out of the permitted muskox management area, according to a news report. The individual had headed northwest from the Dovre mountains area and was moving down from a mountain named Nesaksla toward the town of Åndalsnes.

This wouldn’t have been the first time Åndalsnes had been visited by a muskox. In July 1971, when some young boys came down from a hike on Nesaksla claiming that they had seen a muskox, everyone thought they were ‘crying wolf’. But two men went to investigate and indeed located the muskox on the mountain. In September that year, a farmer’s wife discovered the lone muskox in a forest five kilometers from Åndalsnes when she was picking berries. After that siting, it seems the muskox disappeared back into the mountains, as nothing more was reported in the papers.

In recent years, however, it has been standard practice to ‘put down’ muskox that have moved out of the permitted area. Such was the fate of the muskox killed yesterday.

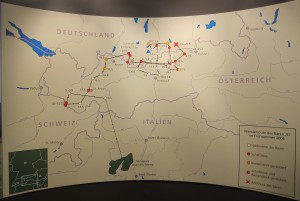

The practice of controlling muskox movements in this way resonates with the story of Bruno the Bear, which I had the opportunity to come face-to-face with in Munich. Bruno’s story is one of wandering, transgressing, and reintroduction. Bruno, whose official scientific designation was JJ1 but was nicknamed Bruno by the press, had been born in an Italian national park. But in May 2006, he migrated across the border to German Bavaria. He became the first brown bear on German soil in 170 years. He had single-handedly reintroduced his species to their former range.

But it turned out to be an unwelcome reintroduction. In the course of his transgressive venture, he supposedly killed 33 sheep, 4 rabbits, and a guinea pig, among other things, as well as raided a honey bee farm. There were attempts to snare the bear for relocation (a group of Finnish hunters was contracted for this), but in the end, he was shot by unknown hunters. Bruno’s life came to an end on 26 June 2006, less than 2 months after moving over the boundary.

Natasha Seegert has analyzed Bruno’s story as one of queering, something “at odds with the normal, the legitimate, the dominant” (a much more general view than the sexual idea of queering). Without taking the Bruno story that far into the realm of queer theory, I agree with Seegert that

Bruno’s presence in Bavaria served as a reminder that space is far more complex and does not always adhere to human-constructed boundaries; that a more-than-human world once roamed the Bavarian Alps long before humans settled in picturesque hamlets and disciplined the landscape. … He challenged boundaries of what is permissible, and normal. By refusing to honor our given borders and cultural norms, he disrupted our human sense of control of the landscape.

The disruption Bruno caused is highlighted in the Museum of Man and Nature (Museum Mensch und Natur) in Munich where Bruno has found his afterlife home. His taxidermied body has been put on display as a problem bear: knocking over a cart, grabbing a hand-full of honey to stuff into his already full mouth. He is unruly and wild, yet strangely anthropomorphised as he stands semi-upright amongst farming technology like a child caught with a hand in the cookie jar (not all that unlike the anthropomorphic taxidermy of Walter Potter). He is nature that has invaded the human world.

It was an invasion that Germans in 2006 were uncomfortable with. It is the same type of invasion that people feared with the muskox headed for Åndalsnes in 2013. Reintroduced animals are fine as long as they live at a distance and don’t bother us as we go about our daily lives. When they step in closer, those same animals become transgressors, meaning that they must be controlled.