A beaver is a beaver is a beaver

I’ve been working on piecing together the involvement of the Skansen zoological garden, Stockholm, in the beaver reintroduction effort. Thus last week I spent some time in the archives to gather more information, as I mentioned in my last post.

Skansen was intended as a Swedish cultural heritage collection and when it opened in 1891, animals related to Sami culture in northern Sweden–reindeer and sled dogs–were included in the display. The zoological collection grew rapidly and focused on Nordic animals, specifically Sweden, as the Director Alarik Behm wrote in the Skansen Zoological Garden Short Guide for Visitors, “giving first priority to get our own country’s fauna represented as completely as possible.”

So when Behm decided about 1901 that Skansen should have beavers, he had a problem. As we know, beavers had been extinct from Sweden for 30 or so years. What to do? Behm turned to Canada.

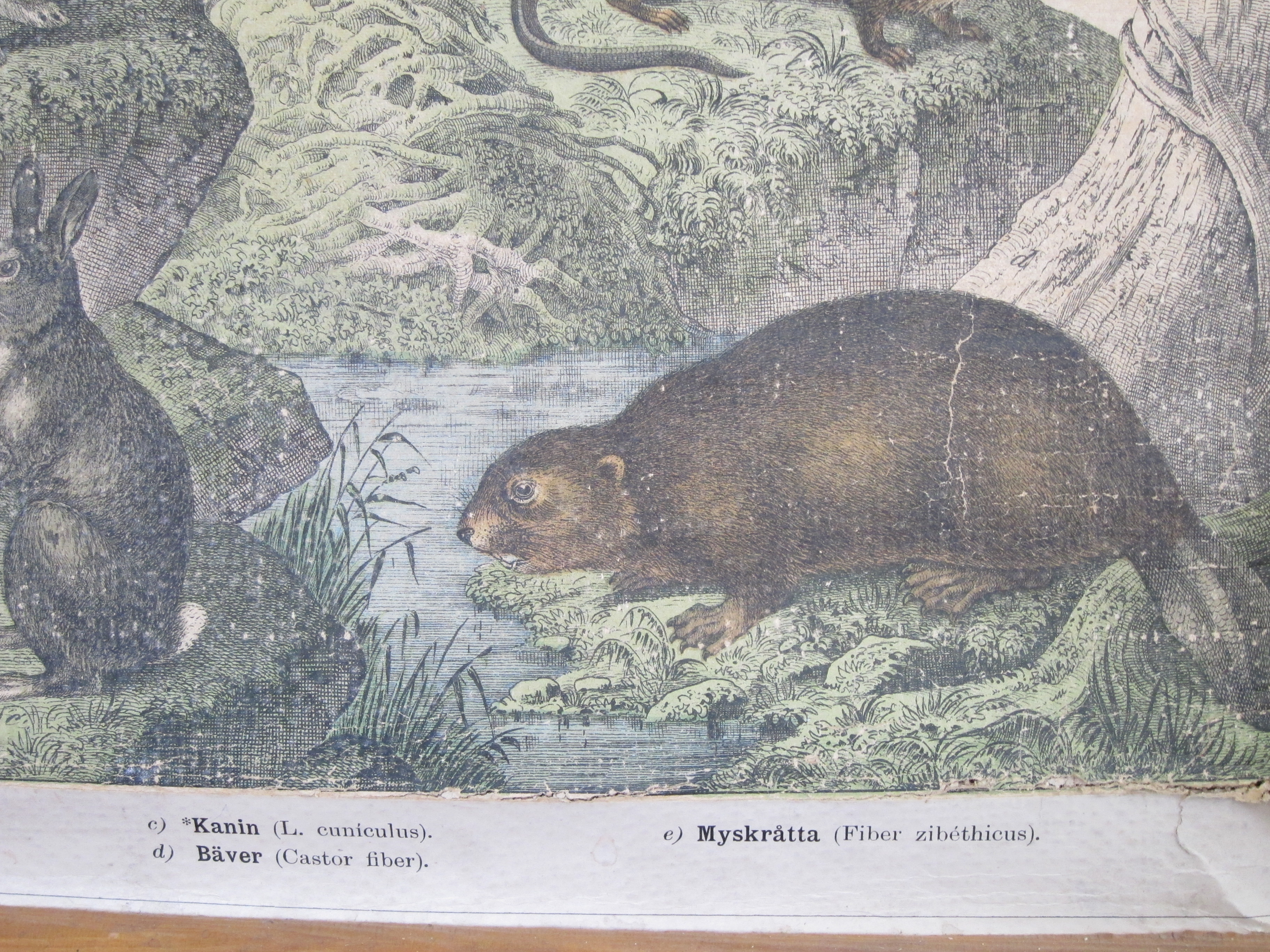

Now, we need to remember that European beavers (Castor fiber) are not the same species as Canadian beavers (Castor canadensis). In fact, the two species don’t appear to be genetically compatible — they can’t interbreed because C. fiber has 48 chromosomes and C. canadensis has 40. But, well, they both look like what you expect a beaver to look like, so Behm probably thought they were close enough for zoo visitors, even though he certainly knew that they were given different species names because the names appear in his own scholarly texts.

A newspaper article from 1901 said that Behm contacted the Swedish-Norwegian consulate in Montreal for help, who then passed the request on to the Hudson Bay Company, who was in turn sending out letters to their factories. It appears that in 1902, Skansen got an offer from a man named Emanuel Ohlén in Montreal. Ohlén (1861-1931) was a Swedish immigrant to Canada and promoted Swedish settlement of the country. (As a side note, somehow he’d also become the consulate for Nicaragua and Peru in Canada.) Ohlén offered two beavers for the price of $200 plus transportation to Sweden. A letter from 22 August 1902 confirms that Ohlén received the money by wire transfer and hoped to bring the beavers that autumn.

Behm clearly had confidence in his Canadian purchase. Already in the Short Guide for Visitors in 1901, there is an entry for beavers. After a description of the animal, the guide notes that “As this is written, two beavers have been bought in Canada on behalf of Skansen’s zoological garden although they had not been sent from that country.” The same text appeared in 1903 and 1905 (although now the common name under Castor fiber was listed as Canadian beaver, which is wrong).

In 1907, the text disappeared. Despair had clearly set in. The Canadian beavers had not materialized. A newspaper article from November 1907 suggested that although Skansen had not been able to obtain beavers from Canada because of the long and difficult journey, the zoo now hoped to get a European beaver from a continental zoo.

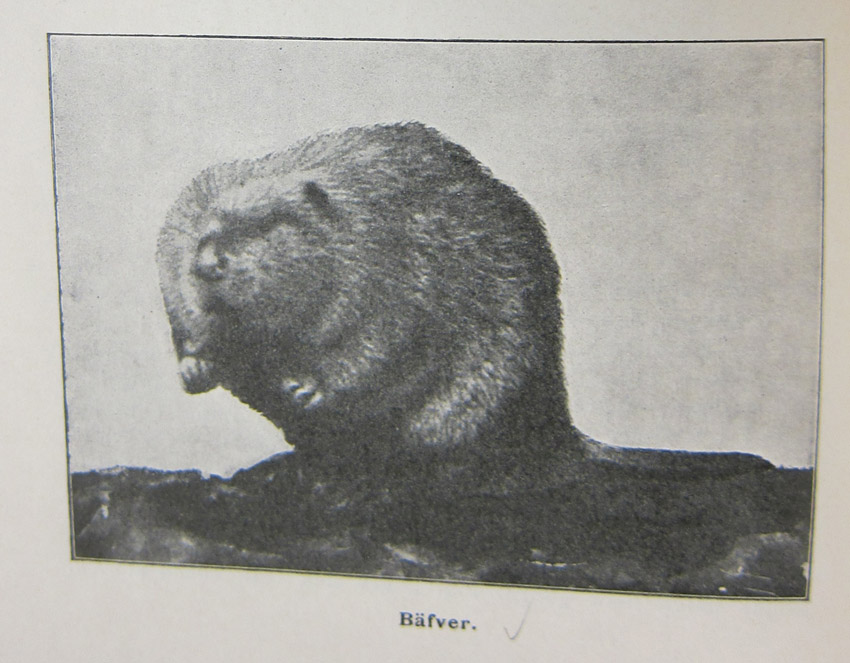

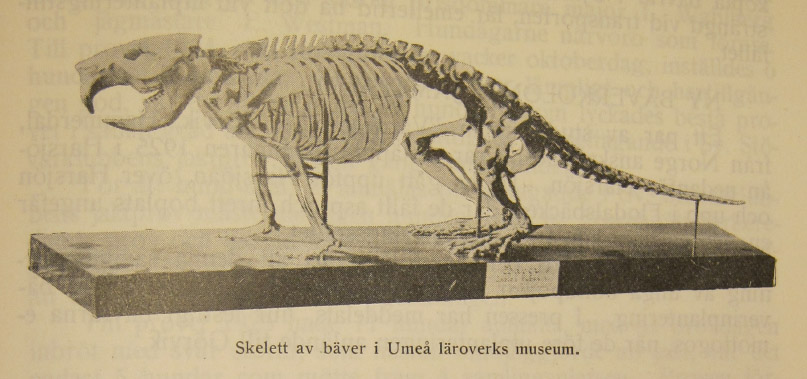

But lo and behold, a Canadian beaver finally showed up on the doorstep in 1909, followed by a second one in 1910, through the work of a donor. It appears the original $200 sent to Ohlén was never recouped. I’m sure Behm was glad to be able to put his text back in the Short Guide issued for 1910 under the rubric “Bäfver. Castor Canadensis Kuhl. Kanadischer Biber, — canadian beaver, — castor du Canada” along with a photo of one of his prized animals.

In the meantime, thinking that Canada was no longer a viable beaver source, Behm had been working his connections with the Berlin zoo to get a European beaver. And in September 1910, three owls were sent from Skansen to Berlin in exchange for one Rhône beaver youth. When it rains, it pours! Everything was looking up for beavers at Skansen.

Then, the European beaver died in 1911. I haven’t been able to find out how – the annual report just says it was “in an accident”. Poor beaver. But the Canadian specimens lived on and the guide books continued to highlight them with an updated photo. They were obviously an important part of the zoo collection.

However a funny thing happened after 1921 when Skansen received the beaver pair that would eventually be taken to Jämtland for release. In the 1922 Short Guide, the entry for beaver was changed to “Bäver. Castor fiber L. Biber, – beaver, – castor” and the text was updated to say that beavers were still found in Telemark, Norway “where Skansen’s beavers came from in autumn 1921.” The Canadian beavers got relegated to the last paragraph: “In a part of the same area there are two examples of the Canadian beaver. They are recognized by the darker fur and wider tail. These came to Skansen respectively in 1909 and 1910.” So the Canadian beavers got sent to the back seat when the European beavers – the more ‘authentic’ Nordic ones – arrived. Behm may have thought a beaver is a beaver until 1921, but he changed his mind when the Norwegian beavers came.

Skansen had Norwegian beavers off and on for the next few years as they served as a pit stop for beavers caught in the fall in Norway but released in the summer in Sweden. The 1924 Short Guide has the same text as 1922. Unfortunately, the Short Guide wasn’t issued after that as far as I know. But if it had been reissued, Behm would have had to change the text significantly since both Canadian beavers died in 1924. Without these permanent resident beavers, would he have continued to include Castor fiber, claiming the beavers destined for reintroduction projects as “Skansen’s”? We may never know.

One Comment

Pingback: