A bird in the hand

At the 2nd World Congress for Environmental History earlier this week in Guimarães, Portugal, I heard a paper by Emily Scott (Swiss Federal Institute of Technology) on the art film Raptor’s Rapture from 2012. The film juxtaposes a live griffon vulture and a flautist playing a 35,000 year old flute made from a griffon vulture bone. You can see a short clip here and listen to a bit of the flute here. Scott discussed the way that the film bridges temporalities (with a prehistoric flute played in the past now played in present and a live vulture in the same room as a bone from its ancestor) and bridges species (the vulture and human are simultaneously there in both past and present). My interest was particularly piqued when Scott mentioned the griffon vulture has been reintroduced in several places, so I’ve done a little reading about them.

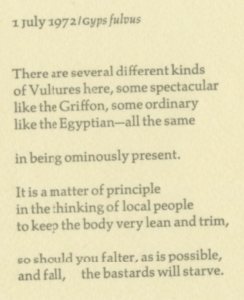

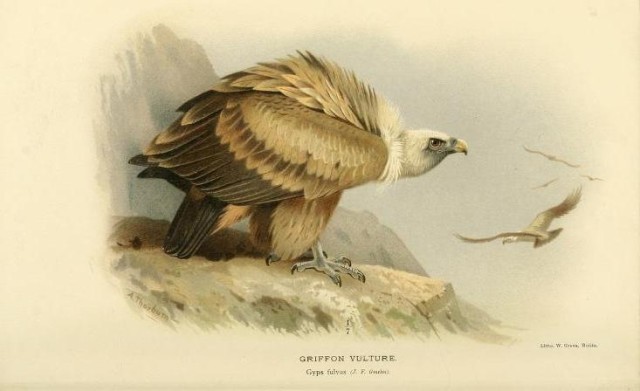

Griffon vultures (Gyps fulvus) are carrion-eating large birds that live in a fairly large range across northern Africa, the Middle East, southern Europe, and India. Although the population is high enough now to be considered a ‘least concern’ species by IUCN, their numbers had markedly declined in the 19th and 20th centuries, mainly because of anti-predator persecution. The antagonistic human-vulture relationship is captured well in the poem ‘1 July 1972. Gyps fulvus’ which I ran across in the Brown Library Digital Library:

Clearly there was no love lost for vultures in 1972 for some people. But at the same time, others were planning to reintroduce the bird in its lost European territories. A reintroduction effort was started in France in 1968, but it took until 1981 to get their first birds from Spain to release. The number of griffon vultures in France had probably been down to 50 breeding pairs, but he highly successful reintroduction efforts doubled that number by 2003. Bulgaria followed suit with a reintroduction project beginning in 2000. The project has had mixed success and failure and continues to the present.

The relationship between human and vulture in Raptor’s Rapture was intimate yet distant. The human interacted with the prehistoric vulture bone but not the vulture in the room. In the reintroduction projects, the relationship is radically different. A video about the vulture’s return in Bulgaria can be contrasted with Raptor’s Rapture. It shows humans breeding vultures in zoos, moving young birds to new homes, holding them up to pose for pictures, and cheering them on to fly free. Human technology looms large in the video: the crates used to move the vultures, the temporary adjustment aviaries, the GPS trackers attached to each bird.

These griffon vultures have been taken into human hands–and, I would argue, moulded and shaped into something more than just vultures in the process. They come to embody hopes and dreams. They represent ‘conservation’ as an ideal. They become intertwined in sociotechnological systems and become technological hybrids. In short, reintroduction demands that humans engage with vultures beyond the disembodied bone flute to the living bird itself.