Missed history-telling opportunities

In my explorations of reintroduction in Norway and Sweden, I’ve been interested in how those human interventions are told (or not) to the public. When I visited the Naturhistoriska riksmuseet (NRM) in Stockholm earlier this year, I couldn’t help but be struck by the many missed opportunities to tell entangled stories.

In the Natur i Sverige (Nature in Sweden) permanent exhibit, the visitors get to meet Swedish fauna, including wolves, red foxes, moose, beaver, wild boar, and the “new animals” I mentioned in a previous post. So I was particularly interested in how the reintroduced animals like beaver and wild boar would be handled.

The beaver exhibit features a beaver dam with some family members inside and others outside. There is a digital information board adjacent to the display where you can read about the beaver’s dam and construction techniques, as well as family life in both Swedish and English. This is in line with on a sign at the beginning of the exhibit on which the designers say that “the exhibit concerns ecology — on the interplay between plants and animals and their environment. …We discuss also animal’s behaviour — on family life, searching for food and reproduction.” The exhibits contain a huge lacuna in what is being presented: people. People have been left out of the animals’ environments entirely. There is no mention that beavers were extinct in Sweden by the 1870s, or that they were reintroduced beginning in the 1920s. There is no discussion of beaver hunting, the historical beaver products of castoreum and furs, or conflicts with forestry and landowners. Beavers become biological entities with no history.

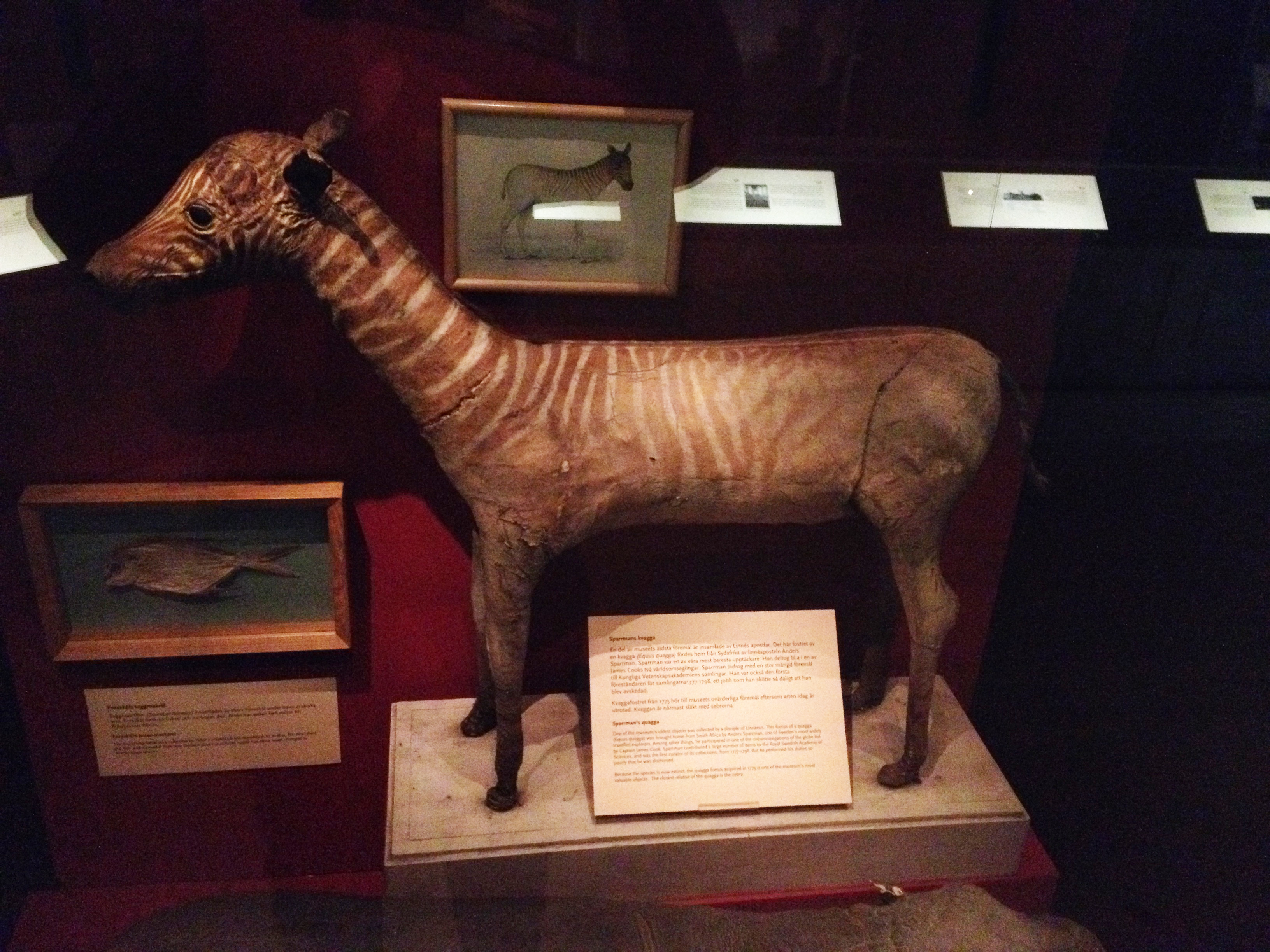

Unfortunately, this approach carries over at NRM even with species that really need to have their histories told because they don’t exist anymore. An example of this is the quagga foetus on display across from the ‘extinct animals’ case. The label with the quagga tells about who collected the specimen and his illustrious career. It also says “Because the species is extinct, the quagga foetus acquired in 1775 is one of the museum’s most valuable objects.” But that’s it. Here was a great opportunity to talk about the history of the quagga, including how the Dutch settlement in South Africa led to its demise, but the opportunity was not taken.

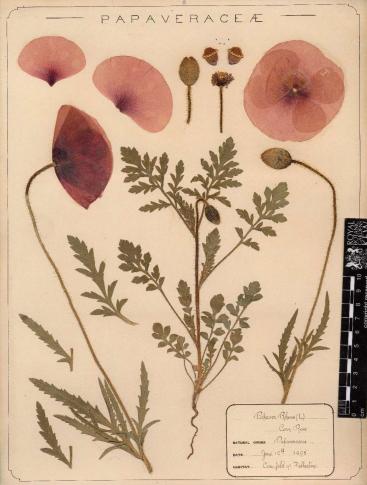

The museum really has a great collection of extinct animal specimens, including the thylacine (extinct 1936), great auk (1844), passenger pigeon (1914), bluebuck (c1800) and many more. But none of these animals are given histories other than the place the species lived and the date of extinction. The general sign in the exhibit simply says “Displayed here are examples of extinct specimens. Some of these have been wiped out by humans, others due to natural causes.” NRM has not taken the opportunity to talk about extinction, what it means, how it happens, and what is lost. The passenger pigeon extinction centennial exhibits are bringing extinction stories to the forefront, and although I would like to see more emphasis on hope in these exhibits, discussing extinction is critical to avoiding it in the future.

While I understand that sharing the biological characteristics of fauna is a central mission of NRM, there are animals in their cases screaming to have their histories told. From the visits I’ve made in natural history museums, NRM’s approach is pretty typical. I think the museum sector needs to take the name “natural history” more seriously and embrace telling animal histories. In so doing, they would be telling entangled human-animal histories that are currently overlooked.

2 Comments

Martin Testorf

Dear Dolly Jorgensen,

Thank you for a very interesting blog post and your in-depth opinions and suggestions on how to improve the storytelling in the museum. We will have this in mind when we continuously work with updates in the exhibitions.

/ Martin Testorf, Communications Officer, Swedish Museum of Natural History

dolly

Thanks, Martin. I work at Umeå University and would be more than happy to collaborate with the museum to help tell some compelling environmental histories with your fabulous collection.