Disloyal muskoxen

In August 1948, 10 yearling muskoxen were taken to Bardufoss in Northern Norway for release into the wild. Two of them apparently died shortly after arrival, but the others made themselves at home in the area around Bardufoss. The Norwegian Polar Institute (Norsk Polarinstitutt) had been convinced to release the calves there by Colonel Ole Reistad, who had led the Bardufoss Air Station forces against the Germans when they invaded in 1940 and became the commander of the Air Station after the war. Reistad died at the end of 1949 and as of July 1950, NP had heard nothing about the calves whereabouts since his death. The NP director A. Orvin wrote a letter to the new commander at Bardufoss airport Lieutenant Colonel John Tvedte asking if there was any news about the animals. Tvedte sent up a special recon flight and reported that two animals were seen in the mountains southwest of Bardufoss. In December 1951, farmer Alf Sundheim reported to the local paper Lofotposten that he had seen all the calves were alive. Correspondence between Sundheim and Orvin confirmed that he had seen seven of the animals, but instead of grouping together in a large flock, they were in small bands of 2 to 3 animals.

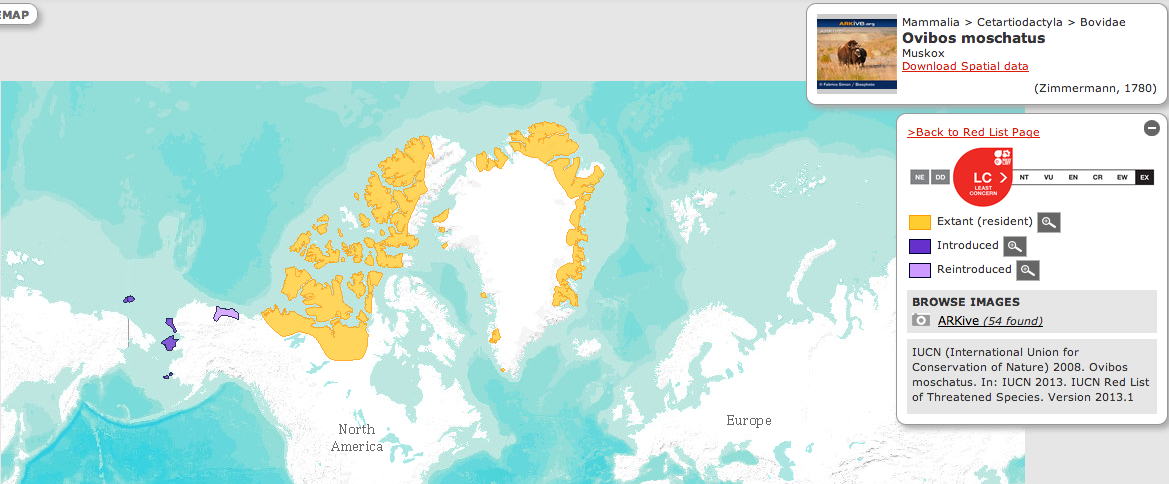

Animals, of course, move around. This is particularly true of herds looking for better grazing. I’ve mapped the places in the correspondence with the Polar Institute to get a visual of that movement.

In January 1953, the Norwegian Polar Institute received word that a group of muskoxen had been spotted in Sweden around Kiruna. John Giæver of the NP asked the Bardufoss Air Station commander to let him know if they happened to catch sight of the animals. There were conflicting reports about how many animals were there–maybe three, maybe just one. The Air Force hadn’t seen them at that time, but the commander noted that there had been little snow before Christmas and all of the mires and streams were frozen, so it was certainly possible that the animals moved over the border.

Giæver’s characterisation of the crossing and the muskoxen who did it reveals how ‘belonging’ was attached to the animals. In Giæver’s words in a letter from 27 January 1953,

It is in principle totally natural that it had wandered over to the brother folk [of Sweden] – even if it must be condemned as disloyal.

Then when he got word that the herd had moved back to the Norwegian side in February 1953, he wrote, ‘It is really more loyal’ (Det var jo faktisk mer loyalt). By saying that the animal is loyal or disloyal to Norway through its movements, Giæver claimed the animal as belonging in the country, with a duty to the fatherland. There is a deep nationalism at play in reintroduction. When the head of Nanok, the Danish company with rights to capture muskox in East Greenland, replied to Giæver’s letter mentioning the disloyalty, he expressed sympathy for Giæver’s position but also understood the muskox:

Although I will give you the right to say that it’s damned unfair for the musk oxen to run over the border to the brother people, on the other hand, it isn’t unreasonable that the muskoxen are dissatisfied with the situation in old Norway, when you consider that they are condemned to live in seclusion.

Seeing it from the point of the animal, perhaps it was a justified desertion of the country. Giæver was probably not sympathetic. He classified the muskoxen crossing the border as ‘a sorry end to this experiment’.

The Swedes apparently did not agree. After the Swedish papers reported the sighting on January 26th, the Swedish government listed the animals as protected on the 31st. The Swedish Nature Protection Association wrote to NP director Orvin that

The muskoxen’s appearance in Lappland is very pleasing and [the Association] will do everything in its power to promote the Scandinavian muskox population’s growth.

The Association requested information about the Norwegian reintroduction efforts, particularly those in Bardufoss since ‘the “Swedish” animals must have come from there’. I noted that they used quote marks around Swedish (‘svenska’) to indicate an unsure assignment of new nationality. When Director Orvin replied to the Association, he noted that they needed to hope there were both cows and bulls in the herd that moved over so that they might have calves and set up a new viable herd.

It turns out that the muskoxen didn’t stay on the Swedish side of the border. By May 1953, they had crossed back. But having the muskoxen, for even such a short time, whet the appetite of Swedes for the animal. The senior editor of the newspaper Norrbottens-Kuriren in Luleå asked the Polar Institute if it would be possible to buy calves for release in northern Sweden. Others from Sweden also wrote in asking for calves. The Institute, however, declined all requests, saying that they were currently only permitted by the Danes to import two calves each year and these needed to be set out in Norway to increase the existing Dovre and Bardufoss herds. Director Orvin noted that the Bardufoss muskoxen might decide to cross the border again and maybe in the future the herd would grow enough to set up a subherd intentionally in northern Sweden. That never happened.

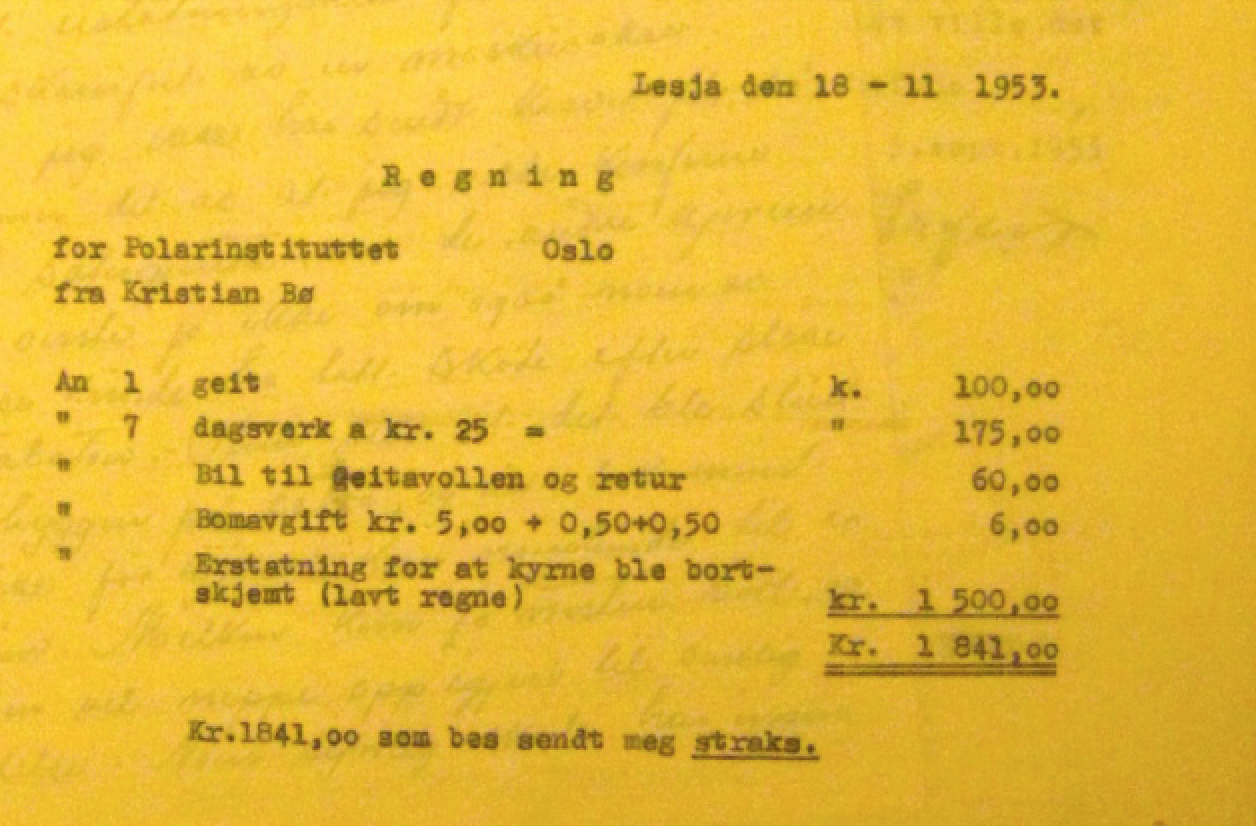

The small Bardufoss herd hung on for a while but died out by the late 1950s, so there was no expansion of the herd into Sweden. The last confirmed information I have about a Bardufoss muskox involves its death. According to a report from April 1958 filed with the Wildlife and Hunting Office, on 16 October 1957, the farmer Alfred Engmo in Bekkebotn (c.23 kilometers southwest of Bardufoss) found a muskox that had gotten itself wrapped in barbed wire. The game manager of the Salangen commune together with the sheriff decided to have the district veterinarian put the animal down. The meat was sold for 3.50 kr per kilo. I was lucky enough to find a photo of that very muskox tangled in the barbed wire on the Gamle Salangen website!

And thus ends the first foray of reintroduced wild muskoxen into northern Norway and Sweden. But it would not be the last migration. The muskoxen would again vote with their feet and take up residence on the Swedish side of the border–in 1971 it would be a group from the Dovre herd taking up residence in Härjedalen. But that is another story.