A search for beginnings

People like to think about the beginnings of things. Understanding the beginning gives a sense of sureness, of identity, because you can know where the things after that came from. After all, the celebration of Christmas, which is all around us at the moment, is all about telling the beginning of a story. You certainly see the tendency in environmental history to search for roots, beginnings, and origins with titles like “The Historical Roots of Our Ecological Crisis” (White 1974) and Gifford Pinchot and the Making of Modern Environmentalism (Miller 2001), and Before Earth Day: The Origins of American Environmental Law, 1945-1970 (Brooks 2009), to name a few. But searching for the beginning can be as treacherous a historical exercise as searching for the last of a species that I previously discussed. How do you know that you have really found the first?

This was one of my dilemmas in my article tracing the various uses of ‘rewilding’ as a term which appeared in Geoforum earlier this month. I specifically avoided trying to trace back all the roots of ‘rewilding’ because I knew that such an exercise was futile for two reasons: (1) I would never know if something had been missed and (2) identifying the inspirations for people’s thoughts is notoriously difficult (even if you interview them). Instead, I decided to focus on the myriad uses of ‘rewilding’ that have agglomerated to form the current popular science use of the term without searching for all possible origins. I limited the scientific analysis to papers cataloged in Web of Science, which I recognise is a database with a restrictive scope, but this made it possible to claim “firstness” in a tangible sense.

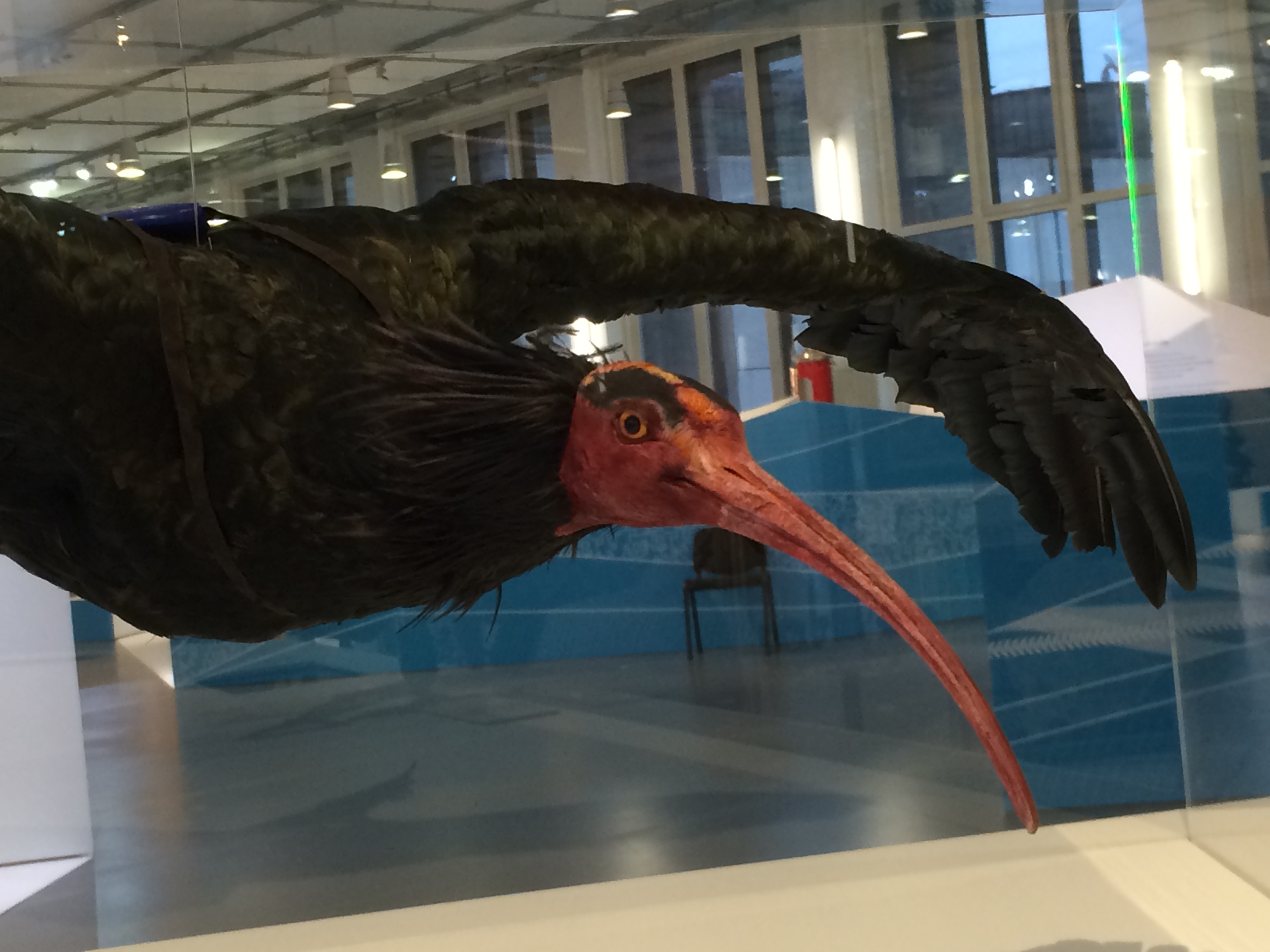

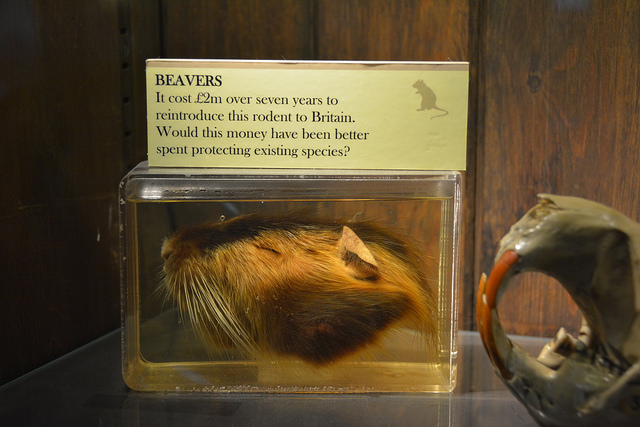

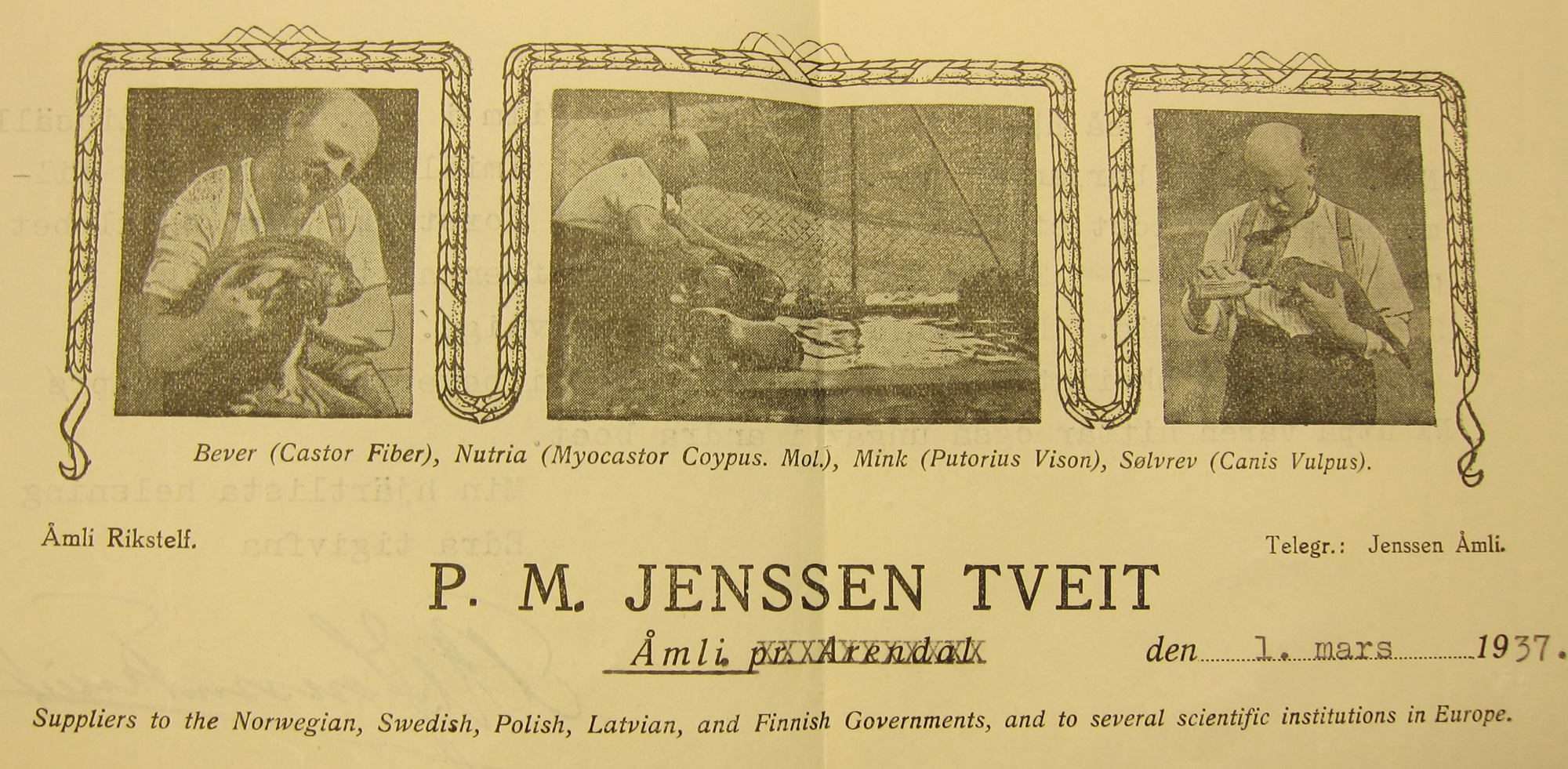

The reason I’m thinking about beginnings this week is that I came across some materials this week that made me realise that the story of beaver reintroduction told by those who brought the beaver to Jämtland (specifically Erik Festin) fails to acknowledge all the predecessors. In Festin’s work, he claimed that inspiration to bring beavers back to Sweden came from himself and Alarik Behm, director of Skansen’s zoo and keynote speaker at an event in Jämtland the year before the reintroduction funding appeal. In an article in 1922, Festin admitted that others had talked about possible reintroduction, including Sigfrid Ericson’s suggestion to reintroduce beaver in Stora Sjöfallets nationalpark in an article from 1921 and Eric Modin’s recommendation in a 1911 article to bring them to the national parks in the north, but these were not direct inspirations. So the fact that he stops there makes sense. For him, the history of the reintroduction begins with himself.

In reality, others had proposed beaver reintroduction long before. All the way back in 1873, F. Unander wrote that the desire for Sweden to have beavers again “can only be achieved through import from abroad and introduction (implantation) of beaver, which also seems to be questioned by Skogsstyrelsen (the Forest agency)”. The suggestion to reintroduce the animal was being made at the same time that the beaver was finally being considered extinct in Sweden (see my earlier post with Unander’s claims about their extinction). In 1884, an article about the beaver’s prior spread in Sweden in Svenska Jägarförbundets Nya Tidskrift closed with:

It would be a loss if such a species would be wiped out, and on the other hand it is a gain for the country’s fauna to possess it as soon as is possible. That Northern Sweden with its immense forest and marshland stretches has many suitable beaver habitats is beyond doubt, and colonisation of the Canadian beaver would not be impossible, but only under the condition that careful protection could be counted on. The previously existing beaver population is now in all likelihood extinct, even if he still exists in the swedish hunting laws. Will the saga ever come true?

Festin’s reintroduction proposal came 40-50 years after these, yet it was his idea that would be acted on and not these earlier ones. On top of that, Festin apparently didn’t even know about those earlier proposals. For him, his idea was new. And in many ways, he was right because his idea led to action whereas the others did not. He did organise the first release of newly imported beavers from Norway.

So where does the story of beaver reintroduction in Sweden begin? Eventually I will partially answer that question by how I write the reintroduction’s history. For now it is an open-ended question. Perhaps there are even older documents waiting to be uncovered. Even if I find others, I’ll never know if I really have seen the first reintroduction proposal. The beginning is just as elusive as the end.