Meeting Martha

I met Martha. Martha the last passenger pigeon.

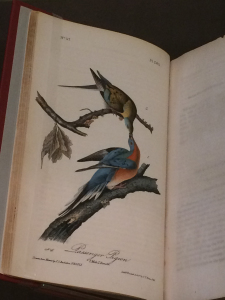

She sat on a branch with her body facing away from me, her head turning in my direction. I stared at her as she seemingly stared back with a glassy red eye. In a way she looked too life-like to sympathise with, to wonder what she had thought about as she spent her last fews years without her mate George. Now she was placed near a potential mate. A male bird, one Martha never knew, reached out with a seed in beak, possibly as an offering to Martha’s passing. But he too seemed too real, too alive. The bird laying down did not. In front of Martha and the male, a passenger pigeon skin specimen lay red belly up and had no eyes. This skin embodied the death of the passenger pigeon. Behind the birds, images of passenger pigeon hunting were reproduced on a grand scale. The images seemed to suggest that Martha and the male would be next to die.

Martha and the others are on display temporarily at the Smithsonian Natural History Museum in Washington DC as part of the exhibit “Once There Were Billions: Vanished Birds of North America” timed for the 100th anniversary of her death, and thus the death of the passenger pigeon as a species. I had a chance to visit while in DC for the American Society for Environmental History annual meeting.

The passenger pigeon bodies were complemented with images and texts about the bird. I made two observations. The first was that the bodies in the cases were not as blue as passenger pigeons were depicted by artists who saw them in the 19th century. All the drawings had the males a pretty bright blue and the females vaguely blueish. Perhaps it was preparation or time that had made these birds fade to grey. Second, the story of the passenger pigeon’s demise as told over the last year in honor of the centenary always makes it sound frivolous, but the exhibit countered that claim. There was a cookbook on display with a recipe for pigeon pie and another for broiled pigeon. I wondered how the pigeon pie recipe would compare to chicken pot pie, a dish I’d just eaten for dinner two days before. Wild pigeons were plentiful and cheap, making them ideal food for the masses. This was a part of their extinction history–their usefulness to humans–which had been downplayed. They were not slaughtered indiscriminately.

Martha and her clan were displayed alongside the Carolina parakeet (the last captive bird died in 1918), the Heath Hen (last one died in 1932), and the Great Auk (extinct in mid-1800s). They each had stories to tell about the end of their species. Warning tales about habitat loss and harvesting.

I saw many people stop and look at the cases when they walked by–although the display was tucked away in a less trafficked area. The story is out there about Martha and the others. Museum visitors were reading it, seeing it. They met Martha, though I’m not sure they all realised the significance of the meeting. But I know that when I met Martha, in a sense, I met humanity. We may be looking at her, but in a ghostly way she is also looking at us, asking us to look at ourselves. How many birds will be on display in the exhibit for the 200th anniversary of Martha’s end in 2115? The answer depends on us.

2 Comments

Laura Pa

I’ve never seen Martha in real life, or her Carolina Parakeet distant cousins, but I feel them and their loss quite deeply. Being a parrot parent and having worked with parrot rescue, the loss of the beautiful conure type parrot that was native to the US and now is never more, hurts. In some ways I am glad that escaped non-native Quaker Parrot/Monk Parakeets are naturalizing in some areas of the US, as they are also a gregarious flocking bird. Not as beautifully colored, but in some ways taking up the niche left empty.

Still leaves some huge holes. Their loss wasn’t caused by habitat loss or climate change, but direct human caused death. What will we have to say when we didn’t directly shoot and kill the ones we are losing now, but who’s loss is our fault nonetheless?

Pingback: