On the time I drank castoreum

Not every historical subject offers the opportunity for a full body experience. My research on beavers, however, does.

Four days ago, I had the chance to drink castoreum (bävergäll in Swedish) liquor. This traditional hunter’s schnapps sold as the brand BVR HJT (pronounced as the word bäverhojt, meaning “beaver shout”) is alcohol infused with castoreum musk from beaver.

The first flavour was similar to oak-cured whiskey, but then the musk comes out. It’s a hard-to-describe taste, but I imagine that it’s what traditional male musky cologne would taste like. It was not particularly strong, however, so it seemed pleasant enough to consume most of the shot.

An hour later, however, I had a different opinion as the castoreum scent started to seep out through my skin – literally. My pores started to extrude the musky smell. My husband, who had simply thought the hotel room smelled a bit funny after we got back from dinner, confirmed that it was indeed me. After a shower, things got better, but I had to take another one in the morning to completely get rid of the beaver odor. My historical inquiry had turned a bit too sensory.

As a historian what’s interesting about this is that I have now experienced what people for a couple thousand years have consumed as a medicinal treatment. Hildegard von Bingen, a Benedictine abbess, mystic, and scholar who lived 1098 to 1179, recorded that fevers could be reduced by drinking wine with either dried beaver liver or beaver testicles (which were in reality castoreum sacs but ancient and medieval writers thought they were the testicles). My drink followed the same principal, although the alcohol was stronger than wine.

Hildegard was repeating ancient medical knowledge that had been handed down since at least Greek times. Aesop’s fables include the tale of the hunted beaver, who bites off his testicles and throws them to the hunter since he knows that is what the hunter is after. This appears as a common tale repeated in numerous works, from Herodotus to late medieval bestiaries. The hunter in these stories pursues the beaver, not for his fur or meat, but to acquire the prized “testicles” for use in medicine.

A fabulously detailed article by Charles Wilson from 1858, “Notes on the prior existence of the castor fiber in Scotland, with its ancient and present distribution in Europe, and on the use of castoreum,” goes through all of the medicinal scholarship of the authorities like Pliny and Avicenna who recommended beaver castoreum for a wide variety of ailments. Castoreum has been found on a medical drugs inventory list from medieval Cairo, so we know it was used in medical practice.

Wilson noted that in his day, the use of castoreum was almost non-existent in Britain and the US, but yet was still used commonly in other places such as France and Germany. In these places, the castoreum from European beaver was much more valued than Canadian beavers, which was considered less effective. The price differences he cites were extreme, with powdered Norwegian castoreum selling for 25 to 35 times the price of Canadian one; which is probably the reason the Norwegian pharmacopia from 1854 directed that Canadian should still be used normally in medicine unless Norwegian or Russian castoreum was specifically requested.

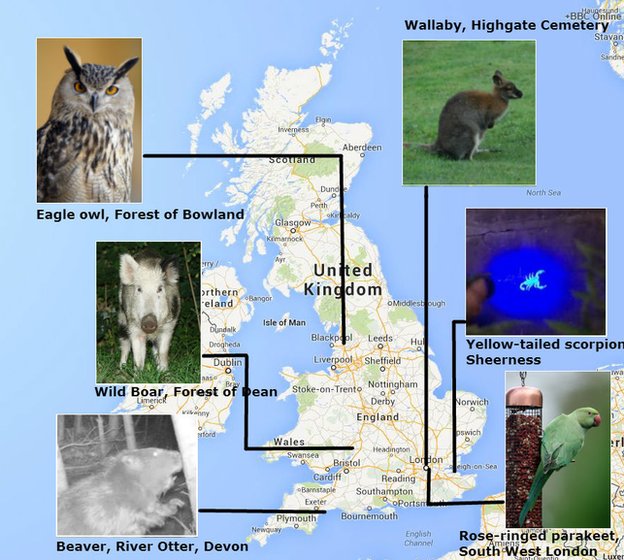

Although Wilson had seen a decline in castoreum prescribed in his home country, it was clearly in use in rural Sweden even into the 20th century. Earlier in July, I visited the Robertsfors Bruksmuseum (industry museum), which has artifacts related to the community of Robertsfors in northern Sweden that grew up around an iron mill. As part of the exhibit, the Robertsfors apothecary shop had been re-created with the store’s original contents (it operated 1917 to mid-1950s). One of the medicinal jars was labelled castoreum. During the period of operation, it is likely that the castoreum being used was Canadian, but it could have also been Norwegian, since by the 1930s, hunting beaver was permitted there.

In articles about the Swedish beaver reintroduction, stories about castoreum as medicine were standard parts of the narrative. In 1922, Eric Festin retold a story recounted by his colleague Alarik Behm in Nordiska däggdjur that same year that I have cited before but it’s worth putting here again:

My grandmother, born in the Jämtland mountains at the beginning of last century, used to tell us kids, that when someone in her home town was very ill and began shaking […], you would give the sick person castoreum, a half teaspoon in a sip of liquor, after which the patient died. Either the medicine was given too late or else it had no effect. This castoreum was supplied by two men, Halvar and Marten, and thanks to their and others’ earnest ‘supplies’, beaver disappeared from the area.

What I think is critical in this narrative is that the extinction of the beaver was not because of hunting for fur or meat, but for castoreum (even if it sounds like it wasn’t all that effective!). Looking at the stress on castoreum as the reason to kill beavers in historical documents, all of the medicinal texts touting castoreum’s healing powers, and the apparent regularity with which it appeared in pharmaceutical preparations, I’m inclined to believe Behm’s grandmother that the decline of the European beaver should be attributed to its musk glands. While beaver fur was certainly useful and harvested in ancient and medieval times, particularly in Russia, it did not really become a mass market fashion commodity until after the discovery of the New World and the new Canadian beaver stocks. Before then, beaver pelts might have been a side product of the really important item: castoreum.

In this light, the European beaver’s near-demise was not unlike the killing of rhinos for their horns to be used in Chinese medicine. The difference was that the beavers lived closer to the users of beaver products, so they saw them disappear, and eventually, worked to bring them back. And that’s something to be thankful for as I sipped castoreum on a summer day in Sweden.

See related posts:

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: