Reintroduction and compensation

One of the most contentious issues with modern reintroduction efforts is compensation for damage caused by the newly returned animals. This came up this week with a heated discussion about reintroduced white-tailed eagles in Scotland that might take lambs. The eagles had died out in the late 1910s and were reintroduced beginning in 1975. Although populations have been established, there are still only about 40 breeding pairs. Inevitably discussion about eagles and their acceptability gets ugly when monetary compensation for farmers who might loose livestock to the birds of prey comes up. An official report for the Scottish government confirmed that white-tailed eagles take lambs on the Island of Mull, so recent claims about lamb losses may be true. Some of the commentators on the recent articles mention of a previous compensation scheme for killed lambs that ended in 2013, but I haven’t been able to find official documentation about it.

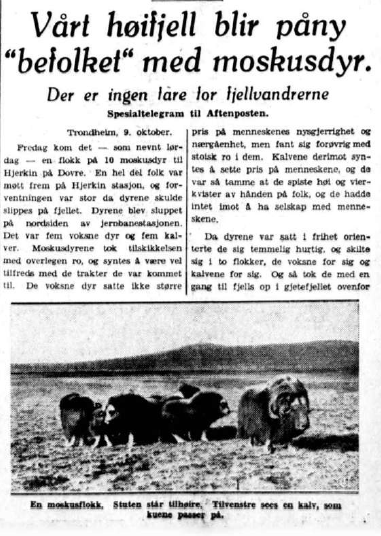

In my research on the muskox reintroduction in Norway, I’ve seen that the question of damage compensation is not a new development.

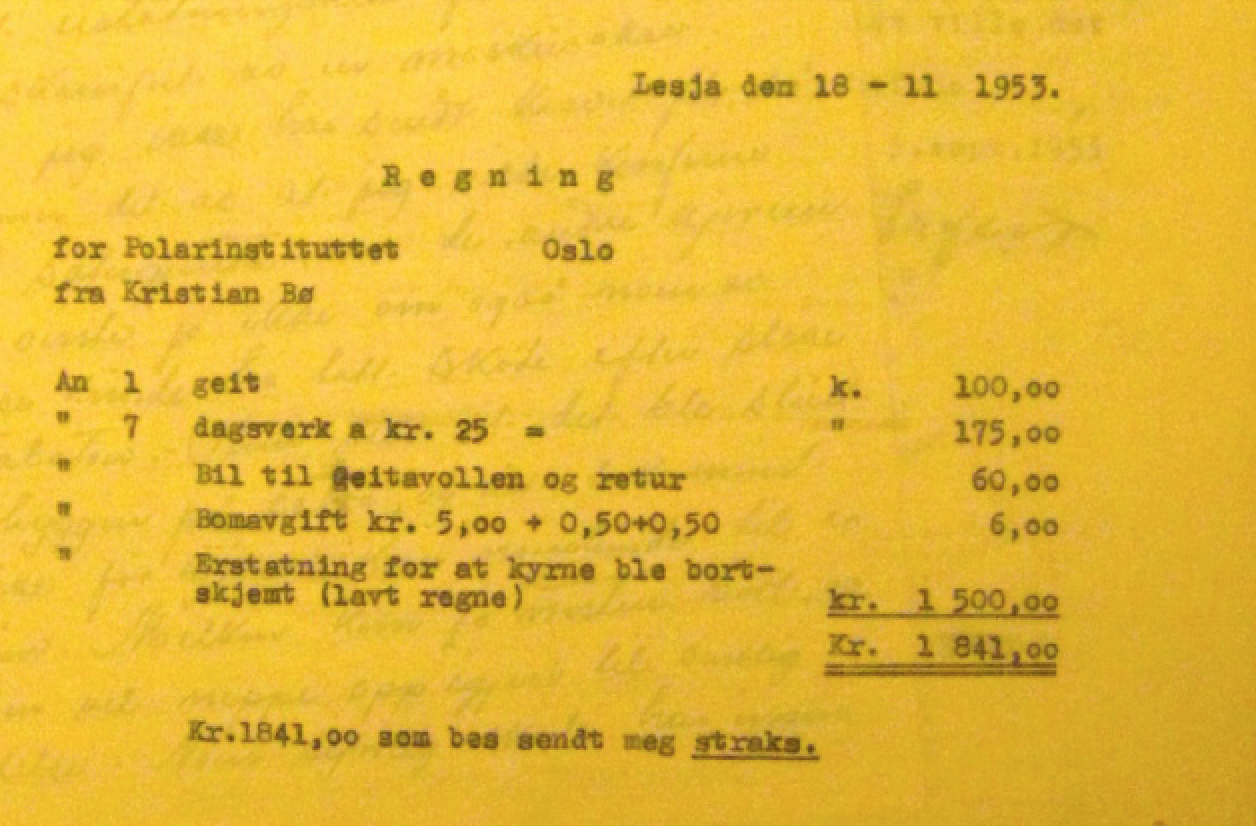

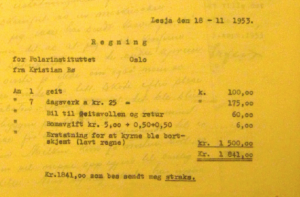

On 18 November 1953, Kristian Bø, a farmer in Lesja, sent a letter to the Norwegian Polar Institute claiming damages from a muskox which visited his farm two times over the summer. The muskox attacked a heifer and scared away two goats (one was never found). His total claim was for 1,841 kr. which he demanded be “sent to me immediately“. The letter was sent via the Lesja sheriff who confirmed the said damages.

Anders K. Orvin of the Polar Institute sent a reply. First, he noted that it was actually not the Polar Institute but rather Arktisk Næringsdrift which had been paid by the State to import the muskoxen. (We should note that Arktisk Næringsdrift was a business set up under the Polar Institute, so while technically separate entity, they are related.) Second, he said that such a claim was quite unusual: “It is not normal that the State will pay compensation for farm animals being scared by a wild animal, and it is also not at all clear that the goat which is missing was killed by a muskox.” Orvin agreed to write to the Ministry of Agriculture to find out their position on the matter, but cautioned that:

It would obviously be unsustainable to have muskoxen in this country if there is a risk of compensation because people or farm animals are scared when they see oxen.

Orvin wrote to the Ministry of Agriculture in December 1953. He made the point that as far as he knew, the State didn’t provide compensation for damage by other wild animals like moose and bear, so he didn’t think paying for muskox damage was appropriate. Arktisk Næringsdrift had set out the calves in 1947, so “obviously [the company] cannot be responsible to animals which were set out so many years ago.”

The Ministry replied that the government would not pay any compensation, but the company should know that if a muskox caused damage, the property owner could kill it without penalty if a special permit was obtained.

With this reply in hand, Orvin wondered in a letter to John Angard (the local man who watched over the muskoxen) if it might be best to pay off Bø, even though the company “has no obligation to do so.” In the end, his reply to Bø in March 1954 said that neither the Ministry nor the company would give compensation:

At the moment that the animals were set out, they became wild animals. The company has no ownership of them and cannot be legally responsible if muskoxen scare farm animals. The animals must come under the same rules that apply for other wild animals.

As you can imagine, Bø was not at all pleased with the reply. He came back with a letter full of questions:

Do I understand correctly that these animals are ownerless? It is then strange that Sheriff Fagersand refused to shoot the ox. Hasn’t the law compensated damage that the same type of ox has done on other farms? Or has it not given any compensation? This is in any case certain: if a muskox comes again, I will not take any chance with my cows and goats. I will shoot it down in an instant.

Orvin’s response tried to be diplomatic, expressing regret that Bø had with the muskox, but he was also clear that the reason the sheriff couldn’t shoot the animal is because it is a protected animal under the law. Orvin also made sure to say that importing a muskox costs several thousand kroner, urging the farmer not to kill them. So the answer was no compensation.

Yet later in the month of March, John Torske of Grødalen notified Orvin that his cow was killed by a muskox. On the 27th, Orvin responded that 1000 kr was being sent via post as compensation, but he made a caveat:

With respect to Arktisk Næringsdrift, it is true that we have paid for damages caused by muskoxen while John Angard was watching over the animals. We have done this totally on our own initiative in order to keep the animals under some kind of control in the beginning. The company has only a little payment from the State for importing calves from Greenland and watch them until they are set out. As soon as calves are out on the land, we have no ownership of them anymore.

Orvin seems to have made a distinction between the claims of Bø and Torske because the latter resulted in the direct death of the cow. But maybe Orvin had decided that it was just not worth fighting the claims.

What this case of compensation shows is that there is a long tradition of conflict between reintroduced animals and people who live near them. Property loss (which equates to monetary losses) are a central part of this conflict. While a wild animal may have no owner, there is a sentiment by the local populace that the government should be responsible for damage caused by it. This most clearly applies to a recently returned animal. How governments handle compensation conflict is a central aspect of acceptance or rejection of reintroduction attempts.