Money makes the world go round

It seems to me that many academics don’t like to talk about money, except when they are talking about not getting a research grant. Even those who love to criticise the liberal economic system don’t really like to talk about money. They don’t want to admit that, as the lyrics from Cabaret say, ‘money makes the world go round’, but it does.

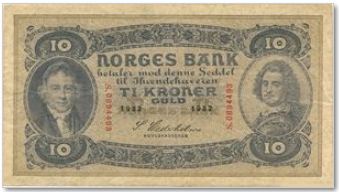

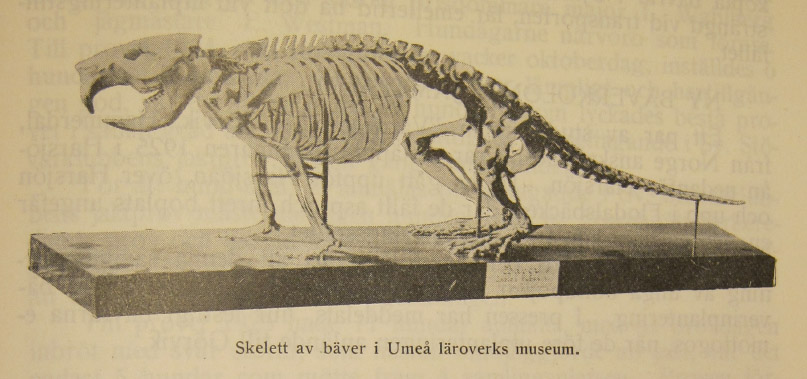

The beaver reintroduction in Sweden I’ve been researching would have come to naught without money. Money was required to buy the beavers, the transportation, the supplies, and the expenses of the caretakers along the way. It was not cheap. The total cost of the reintroduction of the first pair of beavers in Jämtland was estimated to be 3000 Swedish kroner, which is worth about 70000 kr or US$10500 in 2014. So where did this money come from?

It didn’t come from the state or government agencies. It didn’t come from corporations. It came as personal donations from people.

When Eric Festin first proposed the reintroduction, he pleaded for donations in the Swedish Nature Conservation Association (Svenska naturskyddsföreningen) 1921 yearbook:

Jämtland and Härjedalens Naturskyddsförening is close to finalising the preparations, but the association doesn’t have a penny to pay the cost. However, it is really a general national measure to promote this thing and in some way repay past transgressions. The good work of such an effort should not be compromised. It would certainly, not least among the next generation, make an impression and create a broader and better understanding of nature conservation efforts. Who will offer his hand first with an initial contribution for Sweden’s first resurrected beaver colony Bjurälvdalen?

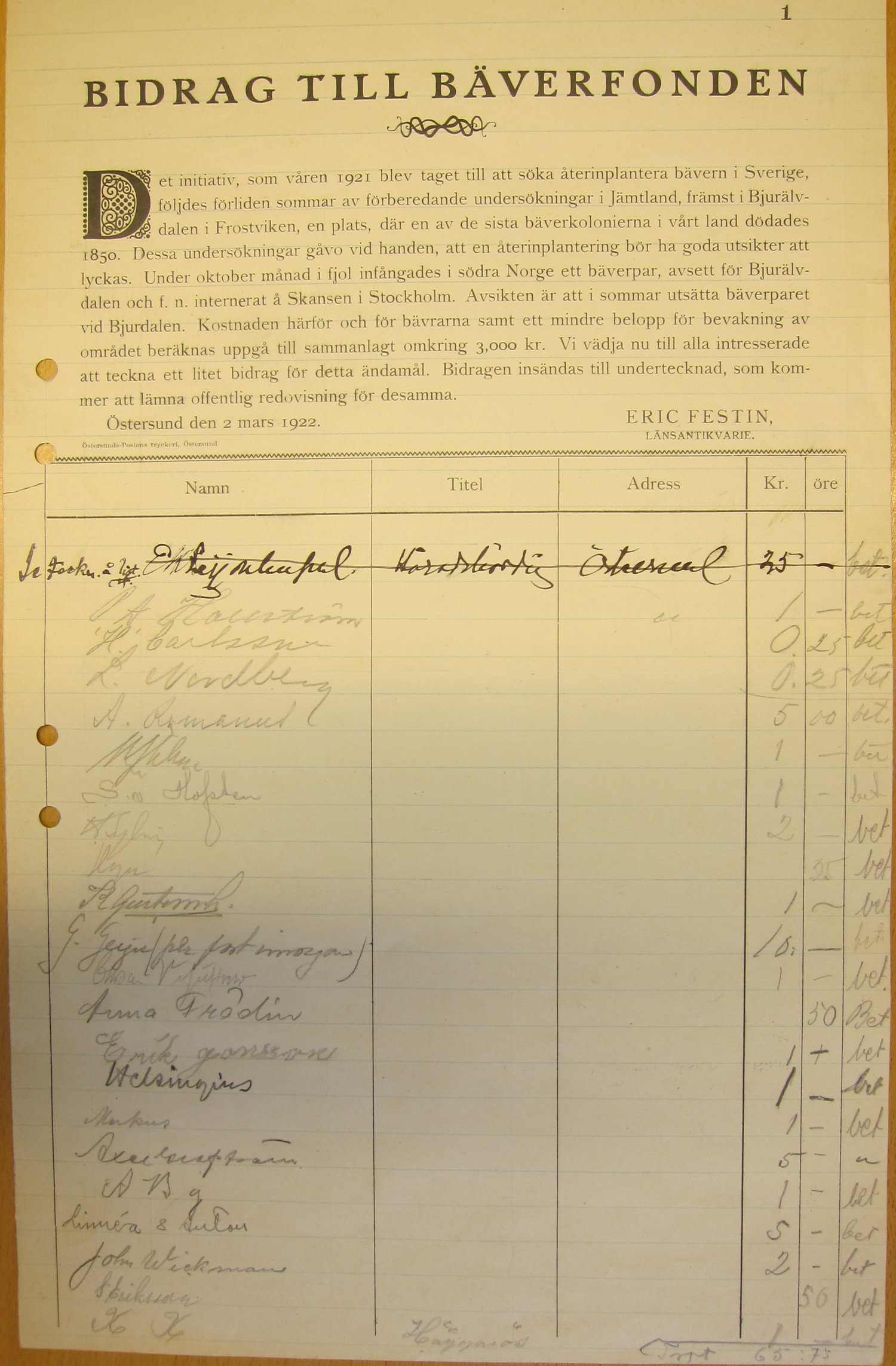

The call was soon answered. The biggest single donation was from Gustaf Werner, an industrialist in Göteborg, who donated 500 kr. More important than the great benefactor is how many people donated very small amounts. There is a whole file for the “Beaver fund” in the Jamtli archive with 96 pages of donations. Many of the pages are filled with names. On the page reproduced here, there are donations as little as 0,25 kr (basically 5 kr or $1 now) and 1 kr appears quite often. These might sound insignificant, but we also have to remember that we are talking about people who lived in rural, off-the-beaten path Sweden in 1922. What the register shows is the great ground support for the reintroduction effort and people willing to pay for it.

In an article written by Sven Arbman, a young zoologist who accompanied the beavers from Stockholm to Bjurälvdalen and had visited their original home in Norway, he told the story of an encounter on the train while taking the beavers:

A group of farmers, on their way home after a forestry course, discovered after the lecture that they forgot to pay admission and so we “scrounged” together 20 kr into our beaver fund. Superintendent Festin in Östersund decided that beaver would be set out in Sweden, and then it must surely happen. With a fund there is surely some means. “Is it worthwhile trying” asked one here on the train, “since you could not guard the treasure up in a mountain valley?” “We rely on upland dwellers,” I said. “So it is,” he said and gave a coin.

From one poor village in Frostviken we have taken in 84 kr. And been promised more. And here a promise means something.

This is the way things worked for all the beaver reintroduction efforts of the 1920s and 30s. For example, a group of nine young men aged 20 to 35 in a study circle named “Vårdkasen” (“Beacon”) raised money to buy the third pair of beavers released in Sweden (in Görvik, 1925). The interest and the money came from below–from average, everyday people. We shouldn’t shirk off individual small amounts, as put together, they made a big difference.

This was the early 20th century version of crowdfunding for conservation. It was widely successful and perhaps an approach we need to mobilize more often in 21st century environmental endeavours.