Treating humans as unnatural

This week I’ve been at the Society for Ecological Restoration Europe 2014 meeting in Oulu, Finland. It’s always interesting to hear how the scientists of restoration ecology and practitioners of ecological restoration go about their work. One of the things that struck me early on in the conference was how many of the projects were restoring human-created ecosystems that harbour rare plant species, particularly open wood pastures, rangeland and grassland which only existed because of livestock grazing. I recently published an article on medieval wood pasture management in the edited volume European wood-pastures in transition, so I liked these restoration projects. However, I noticed that not many people overtly said that they were restoring anthropogenic landscapes. It was almost as if they didn’t want to admit it was what they were doing.

Then today I went to a paper about “non-native” species in “contemporary human-made habitats” (those were words in the title). Those habitats were defined as places that had previously had intense effects, like wetland drainage, mining, forestry clearance, etc., but it didn’t include those more positively viewed anthropogenic habitats that I had noticed in other papers. I could live with that, but what really bugged me was the definition of “non-native”. I’ve mentioned before the inconsistent time frames which European countries use to determine eligibility for Red List purposes. “Non-native” in plant circles comes in two categories: archaeophytes (species which arrived anytime from the Neolithic to 1500) and neophytes (species which arrived after 1500). Any plant that arrived in the speaker’s study area of central Europe after around 7000 years ago, i.e. since humans migrated to the area, was a “non-native”.

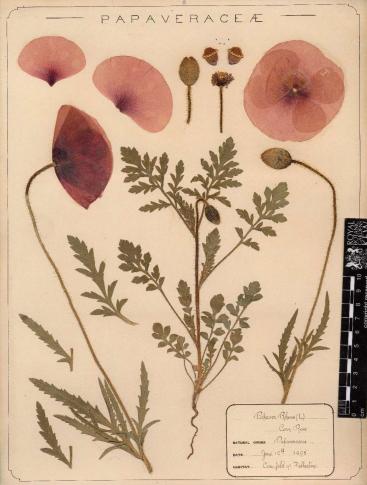

To me, that seems like a ridiculously long time for a plant to be going about its business growing and reproducing for it to still be considered “an outsider”. I asked myself, how long is long enough? After all, archeophytes like the common poppy–you know the red one covering the European fields of the World Wars and now pouring out of the Tower of London–have been in northern Europe for thousands of years but not before the Neolithic. I came to realise that the labelling of a plant as “non-native” isn’t really about time–it’s about agency. Plants that humans brought are “non-native”. Humans brought these species either accidentally or intentionally as they expanded throughout Europe. So what it really comes down to is that those plants which came from the Neolithic onward are considered “tainted” by humans. Seen in this light, the vegetation can never be “native” because the spread of these plants is “unnatural”.

The problem with this definition of “non-native” is this: The spread of plants which come along with humans can only be considered “unnatural” if you think that humans and what they do are unnatural. It only puts up more walls between humans and nature–walls environmental historians need to work on breaking down.

2 Comments

Mark Anthony

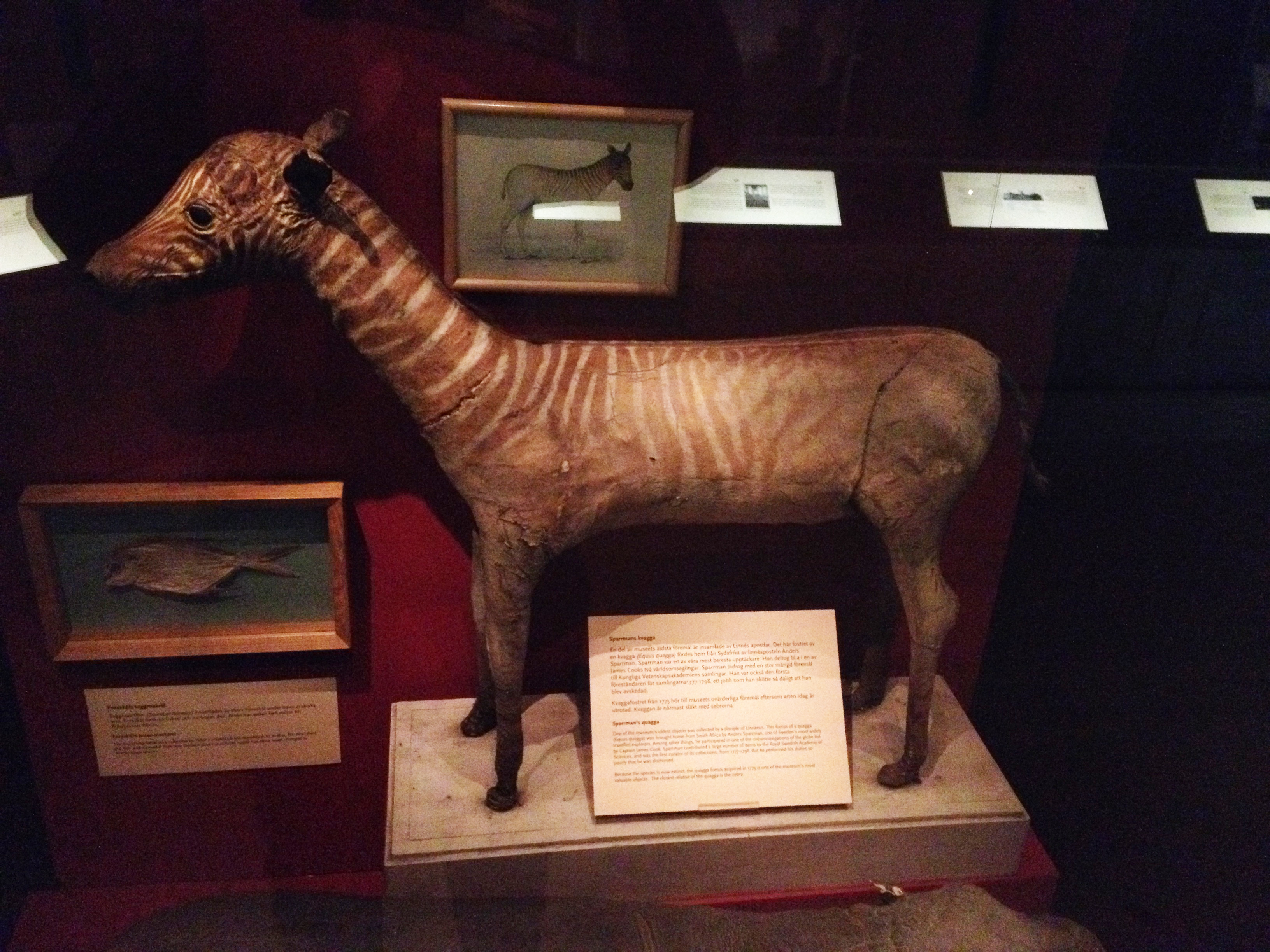

I see your point. Almost all the landscapes in Western and Central Europe are moulded by humanity. There’s only one primeval forest left, that goes back 10000 yrs (in Eastern Poland). Many species that thrive now on chalk downland or upland heather moorland, for example in Britain, and which conservationists are keen to preserve or restore, live or lived in man-made environments. But because these creatures have evolved alongside human activity and become dependent on it, these places should be regarded as natural ( or as natural as can be, unless we go back to one virtually continuous forest). They are important because of the diversity they offer. The biggest nightmare is the mono-culture of modern farming. Even if a species is considered a newcomer or an alien invader, yet offers a depth to an already impoverished Eco-system, should it not be welcomed? For example ring-necked parakeets in Southern England. Also, if species that once lived on these shores, now extinct, are re-introduced, but from foreign stock, such as Russian Great Bustards for Salisbury Plain or Norwegian Sea Eagles for the Isle of Mull, this is preferable to accepting the loss of the species here on purist grounds. And as climate change progresses, more and more alien species will find themselves on the move and able to colonise new territory, so the old distinctions about what is natural and what is not will become spurious.

Pingback: