Locals in the landscape

This week, Eric Michael Johnson published a piece at Scientific American, ‘Fire Over Ahwahnee: John Muir and the Decline of Yosemite’, about the drive by conservationists to both extinguish fire and the indigenous peoples who lived in the areas which would become some of the most famous ‘natural’ wonders in the US. This is a sad tale that many people within the field of restoration ecology are only now coming to grips with–the very thing that was valued was not ‘wilderness’ but rather anthropogenic. This resonated with my recent thoughts about the tendency to de-humanise thoroughly human landscapes. But it also got me thinking about whose interests get to count in nature conservation.

When Adolf Hoel decided that muskoxen should be reintroduced into the Dovre area of Norway, no one consulted the local population. At the beginning, there were concerns about safety hiking in the mountains. In the wake of a muskox attack which left a 74-year-old local man dead in 1964, the local farming community was even more concerned about the safety of children walking to school and potential deadly encounters on their farms. When the farming community of Engen sent a telegram signed by 122 local residents to the Ministry of Agriculture demanding that the Ministry remove the muskoxen, they got only a lawyer-speak response about the legal protection afforded muskoxen. Their concerns were not addressed.

When a small muskox herd moved over the border from Norway to Sweden, many people were happy. The tourist industry was particularly excited to have a new draw to the area. But some people were unhappy. The Sami reindeer herders were particularly displeased. The muskoxen had moved in the same area where their reindeer fed and this meant human-muskox encounters, something they wanted to avoid. In a letter from 1978, the Tännäs Sameby representative asked the environmental agency to not allow the herd to grow bigger more than 20 muskoxen. The Sameby also wanted a ban of muskox monitoring activities from 20 April to 15 June during the reindeer calving period. Although the county administration agreed with the Sameby’s position and forwarded these recommendations to the environmental agency (Naturvårdsverket), the memorandum of 10 May 1979 which defines procedures for handling muskox in Sweden does not address any of those concerns. In fact, it doesn’t mention reindeer herding or the rights of the indigenous peoples in the area at all.

What these two incidents have in common is that the local voices didn’t count. Someone far away in the capital got to decide what the ‘right’ relationship between people and animals should be. This is precisely the same kind of interaction I saw in the dam removal controversies I researched–the local people are discounted from the conversation because they are considered ‘uneducated country folk’ rather than parties with valid interests. I think reintroduction projects often face the problem of privileging the ‘common good’ (i.e. the good as defined by policymakers and scientists far away from the site) over the ‘local good’ (i.e. the local inhabitants and their needs and wants).

The beaver reintroduction in Scotland is a perfect example of this. In the report summarising the public consultation, which is a required part of the reintroduction process if you are going to follow the international IUCN guidelines, the conclusion was reached that a majority of people want the reintroduction, therefore it should move forward. But if you read the details, you see that the majority of the people who lived in the immediate vicinity of the reintroduction site were against it. It all comes down to how you define ‘local’ residents and whose voices are heard. I’m not saying that the trial shouldn’t have gone forward, but I am saying that we need to think about whether ‘public consultation’ in nature conservation and reintroduction projects is real or just lip service. Are the surveys and information gathered just to support the previously-decided outcome? Or are the consultations really part of the decision-making process?

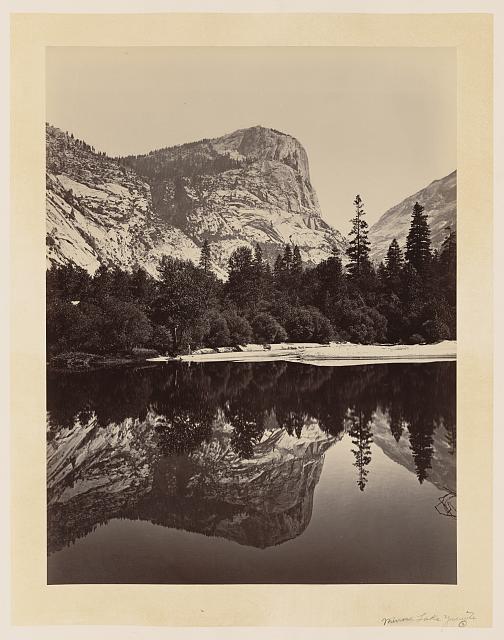

When John Muir looked at Yosemite, he saw a natural wonder. What he didn’t fully grasp is that the people living in that landscape mattered tremendously. Wouldn’t it be a shame if after 100 years we still continue to do the same?