A political object

Last week Tina Adcock, environmental historian at Simon Fraser University (Canada), had a series of tweets about muskoxen she was discovering in some Canadian documents:

This, of course, got me thinking about why muskoxen garnered political attention in Scandinavia in the early 20th century.

One of the reasons Adolf Hoel gave for bringing muskox to Norway was to smooth over political troubles with Denmark. Norway and Denmark were arguing about control of Greenland. In 1814, the Treaty of Kiel required Denmark to cede Norway to Sweden, but Denmark retained all other territories including Greenland. When Norway became an independent nation in 1905 (free from Swedish rule), Norwegian officials started discussing whether or not Greenland should be part of Norway. When Denmark claimed sole sovereignty over all of Greenland and its waters in 1921, Norway objected. Norway believed they had a claim to resources in East Greenland where Norwegian seal hunters had been operating since the 19th century.

On East Greenland, Norwegians hunters often killed muskoxen for food and gave it to their sled dogs. In addition, there had been a high demand for muskox calves to send to zoos around the world — and catching calves meant killing the adults. The muskox population showed signs of decline. In December 1926, Landsforeningen for Naturfredning i Norge (Association for Nature Protection in Norway) wrote an open letter to the Norwegian Foreign Affairs Department criticising these practices. They pointed to Canada’s recent establishment of large arctic reservations in which it was forbidden to kill muskox. The group recommended that a clause be added to the pending agreement between Denmark and Norway on Greenland specifically about preserving rare or useful species. Then in 1929, the report of the 18th Scandinavian Naturalist Congress, which was held in Copenhagen, declared that:

Now the time has come, which we fear, that muskoxen will be extinct in East Greenland north of Scoresby Sound, and consequently the governments of Denmark and Norway should immediately take measures to protect the muskox. And why should Denmark and Norway not be in agreement about this issue and follow the stellar example which is set by Canada, where the muskox’s existence was also threatened, since both its area of distribution and number of individuals was greatly reduced? Already for several years muskoxen have been strictly protected in Canada, and only in great emergency are the native population (Indians and Eskimos) and scientific expeditions allowed to hunt the animals.

The nod to Canadian protection of muskox refers to the ban on muskox hunting, which according to the secondary sources I’ve read came into force in 1910, and the establishment of a wildlife sanctuary at Thelon to protect muskox in 1927.

This is the political context within which Adolf Hoel, founder of the Norwegian Polar Institute, brought muskoxen to Svalbard for release into the wild in 1929. The political implications were clearly on his mind. In the article ‘Ovreføring av moskusokser til Svalbard’ from 1930, Hoel wrote that the muskox translocation

has national meaning for us. We Norwegians are a hunting people, more than anyone else on the whole Earth. We often hear critique that we exterminate the ocean’s mammal, whale and seal, and fur-bearing animals like arctic fox and polar bear. This critique hurts us in many ways. This attempt with transplantation of muskoxen can partially answer this critique; we will show with it that we don’t only slaughter, but that we too support cross-border idealistic cultural work.

The muskox then was more than just a source meat or wool. It was part of a political struggle over natural resources in Greenland. The struggle would only get more intense.

In 1930, the Norwegian and Danish authorities were negotiating about muskox protection measures in East Greenland (this is documented in a series of “verbal notes” between foreign affairs departments in the National Archives). Denmark proposed a complete ban on shipping muskox, which would in practice mean no trade in meat, furs or calves. The Norwegian counterproposal allowed taking of calves with permission, killing of adults for food for overwintering hunting expeditions but not to feed sled dogs (except entrails), and import of meat to Norway would be forbidden. The Danish government rejected this proposal saying it wouldn’t solve the problem.

In 1931, a group of Norwegian hunters ‘occupied’ land in East Greenland where they had traditionally hunted, claiming it for Norway. The Norwegian navy were ordered by Defence Minister Quisling to support the action. The two nations were close to war. Norway and Denmark agreed to let the international court in the Haag decide on the claim. In 1933, the court ruled that Denmark was the holder of Greenland according to the Treaty of Kiel from 1814. Norway agreed to honour the decision.

Even after the decision, Danes and Norwegians (who were allowed to continue to have hunting operations on Greenland) continued to spar about muskox protection. A newspaper editorial by Professor Jon Skeie titled ‘Danish agitation against Norwegian hunters’ in June 1933 fought against the ongoing Danish portrayal of Norwegians as killers of muskox. It was the Danish, he argued, who hadn’t agreed to the Norwegian proposal in 1930, which would have been effective. And it was the Danes who continued to eat muskox meat during expeditions. The Danish State Inspector for East Greenland Ejnar Mikkelsen held a lecture in March 1935 criticising the failure to protect muskox in East Greenland. Adolf Hoel took issue with Mikkelsen’s lack of numbers to show whether it was really Norwegian hunters who were the problem or Danish ones too: ‘The Danish are as good, or as bad, as the Norweigans when it comes to shooting muskox.’ Hoel was personally offended by Mikkelsen’s critique of the importation of 17 muskox calves to Svalbard in 1929. Hoel answered that preserving muskox was part of his motivation for the action, so it should be praised. In the end of his 5 page letter to the Norwegian government with his thoughts about Mikkelsen’s talk, Hoel reaffirmed that Norway should be committed to preserving muskoxen, but a total protection in the area proposed by Mikkelsen was unacceptable because ‘the most important Norwegian hunting area would be directly harmed’. This was a tricky game of politics.

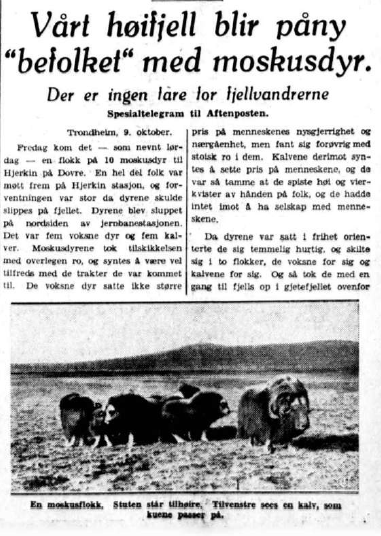

No easy solution was at hand. It took until 1949 before the Danish government established comprehensive regulations for hunting and trapping in East Greenland. The rules gave the Norwegian government the right to transfer a total of 20 calves to Norway from 1949 to 1954 with a ceiling of 60 adult animals shot in the process. The Polar Institute used this quota for calves released in the Dovre mountains and Bardu. After that point, calves were no longer caught in Greenland for Norway. The herds had to survive without further additions from Greenland.

Politics. Politics looms large in nature conservation. Administrations in Denmark and Norway were indeed ‘absolutely obsessed with muskoxen’ as Tina noted. As Norway and Denmark fought about hunting practices and land claims, muskoxen became a political object enrolled in a larger political struggle.

One Comment

Pingback: