Stories of the past for the future

Earlier this week I gave a talk at my university about the role of memory in the reintroduction of beaver to Sweden in the 20th century. I’ve been working on this piece for a while and will be giving another presentation on it in Lund in southern Sweden in a couple weeks.

In working on this, I’ve read a fair amount of scholarship about memories that transcend the individual as social memories, or ‘collective memory’ as Maurice Halbwachs calls it. Scholars after Halbwach have further refined ‘collective memory’, splitting it into ‘cultural memory’, which is institutionalized, recounted by specialists and requires external symbols to invoke the memory (things like religious practice are often in this category), and ‘communicative memory’, which is non-institutional, based in everyday action and has a limited time depth of 3 to 4 generations. This idea of ‘communicative memory’ struck me as very relevant to the beaver reintroduction case.

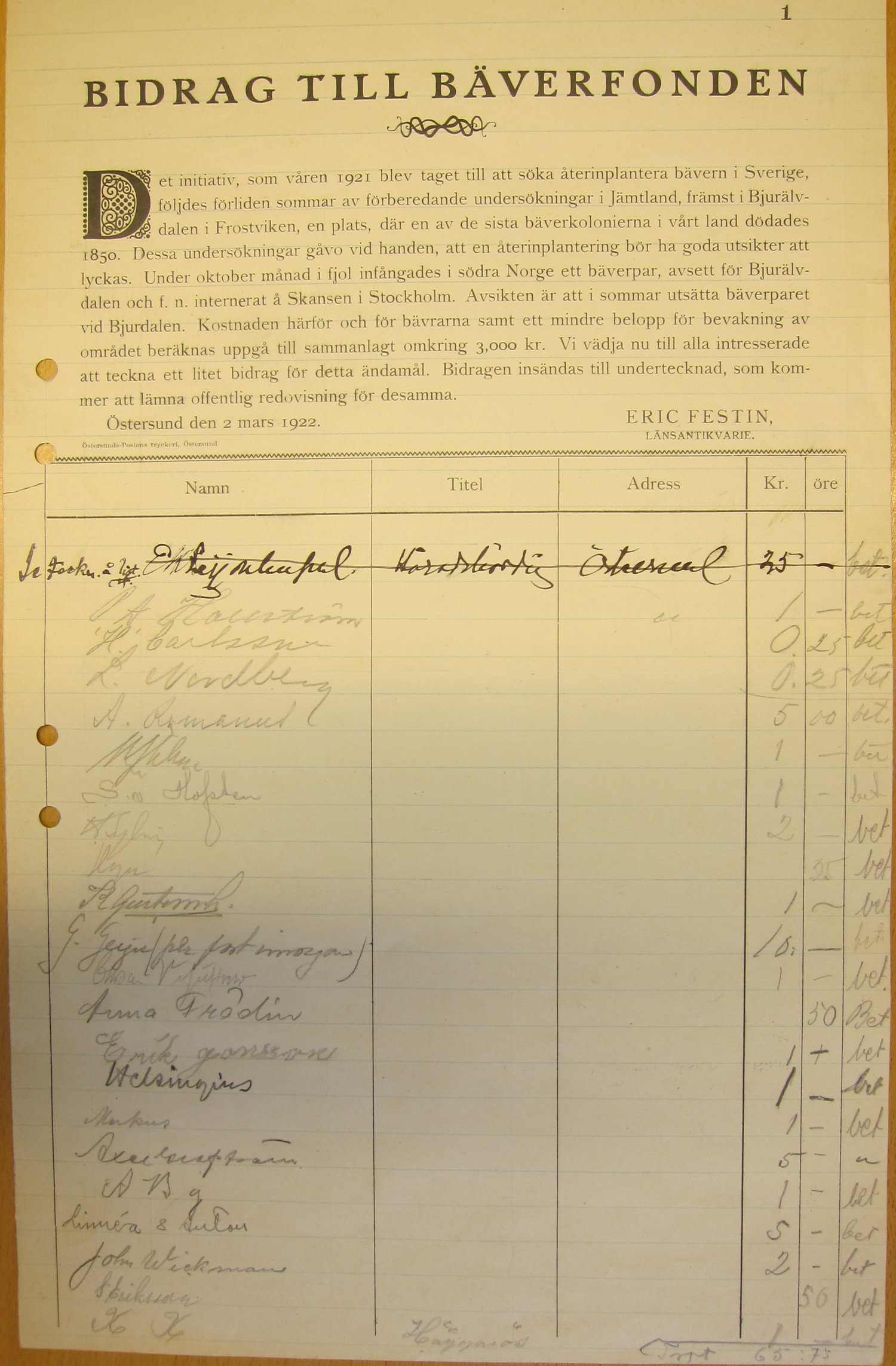

When the first pair of beavers were brought from Norway to Sweden in 1922, stories about beavers were told and new stories were made. When Eric Festin wrote an appeal for funds in 1921 to the members of the Nature Conservation Association, he claimed that not only was Bjurälvdalen (literally ‘beaver river valley’) in Jämtland the right fit for the reintroduction because beavers once lived there, it was also had the right communicative memory:

Jämtland is perhaps also our single province where the legends about the beaver still live on in people’s lips.

His article included the recounting of memories of the last beaver killed in Bjurälvdalen in 1850 by Pell Persson, a man known as ‘the beaver slayer’ (bjurdödare) who ended his own life. The memory of beavers in both life and death was part of the reintroduction project’s framing from the beginning.

During the beavers’ journey from Stockholm where they had stayed in the winter of 1921-22 to Bjurälfdalen , a number of stops along the way generated public interest. In Östersund, Sven Arbman, the zoologist who had done research about the Bjurälfdalen release site and had been to southern Norway to acquire the beavers, gave a natural history talk about the beaver and urged the children to have the first look at the beavers because “this is for the future.” This is the moment captured by the photographer Nils Thomasson who joined the journey in Östersund. In the photo, a young boy stands next to Arbman, who is picking up the beaver, and Festin who bends over to see the precious cargo. Such talks were a way of transmitting the memory of the event to the spectators, particularly the children, who were singled out as important recipients of the experience and narrative. Storytelling is about transmitting memory to the next generation, as well as transmitting it to new places. It is the way that memory travels through space and time.

The memory of the beaver in Sweden was transmitted through communicative memory. The stories of old–the killing of the last beavers as well as the traditional medicinal uses of beaver castoreum–were told and retold. New memories were intentionally cultivated in the reintroduction process using these tales as well as new experiences.

I think there is a lesson to be learned about the way that support for reintroduction projects works. Memories matter. Deploying communicative memory as a framework allows me as an environmental historian to think about how relayed historical narratives change the way people think about and act to address environmental issues in the present.