2014 in review

My previous post marked the 150th post of this blog and the year is coming to a close, so I thought it would be a great time to review what I wrote about in 2014. Although this blog is based on my research about beaver and muskox reintroduction in Norway and Sweden, I range far and wide in applying my research insights.

Ongoing news about the beavers in the British Isles was worth comment several times, including coverage of the beavers discovered in Devon and their potential cull because of fears of disease. For some, the beavers are a lost species who is wanted back in Britain. For others, including the media, it’s been unclear whether the beaver has native or non-native status, but that hasn’t stopped proposals for more beaver reintroductions like in Wales. As noted in an exhibit in the Grant Museum, the question still remains whether or not money would be better spent on conserving animals already present in Britain rather than bringing in extinct ones.

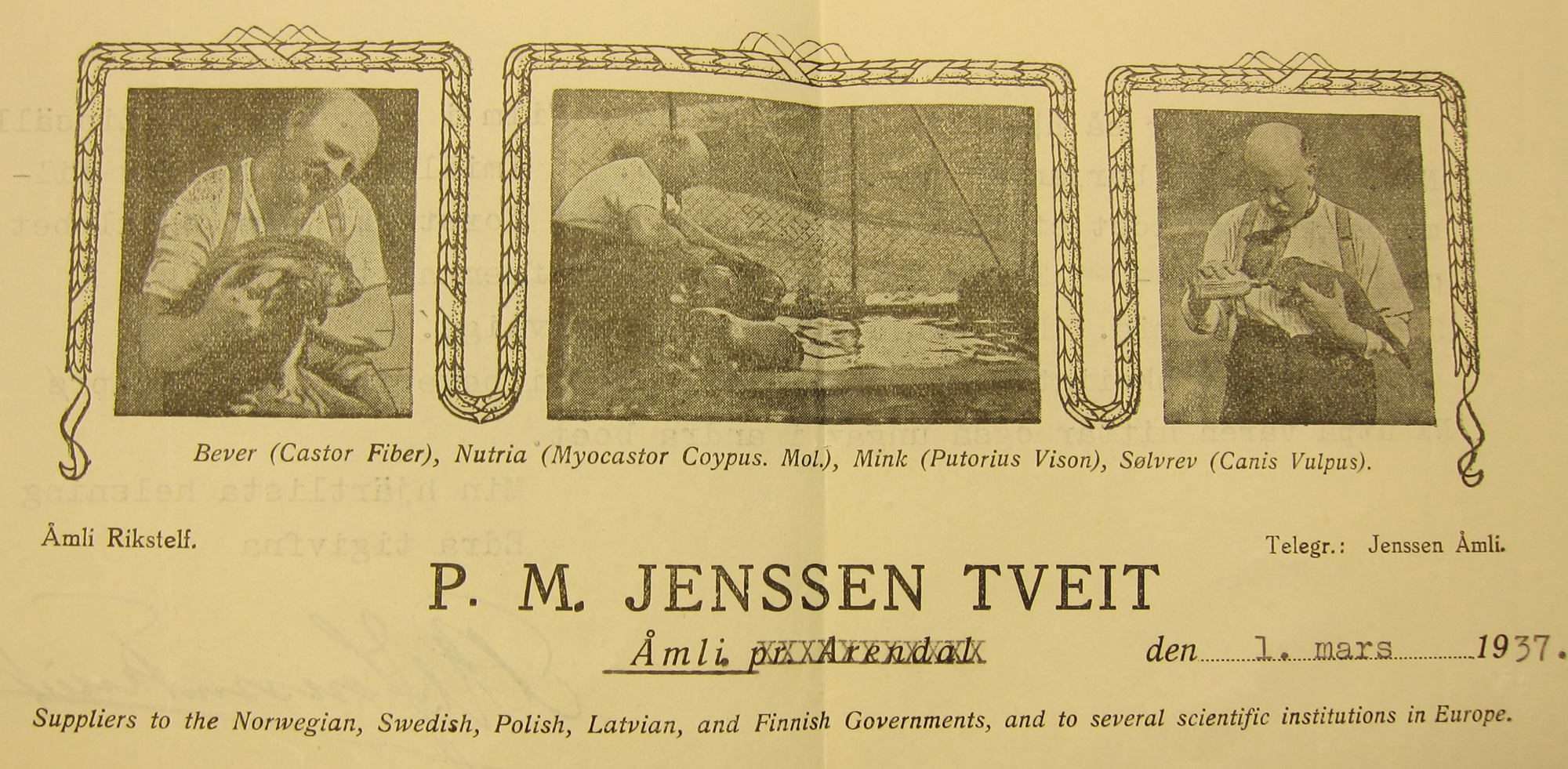

Of course, I didn’t restrict my discussions to British beavers. My travels during the year brought me in contact with the histories of beavers in other places, including Latvia, Berlin, and my nearby zoo in Lycksele. I also commented on the Canadian beavers which had been brought to Finland. And I can’t forget to mention the flying beavers reintroduced via parachute in the US.

My favourite beaver post of the year had to be about eating beaver for Lent. It’s a great example of how medieval history and modern history can intersect. Of course, being trained first in history as a medievalist, I like to bring older history into the blog, which I did with posts on otters appearing on Olaus Magnus’s 16th century map of the North and the animals in the early medieval Life of St. Cuthbert.

My most read post on this blog is about beavers too, but it’s actually from 2013. “On the time I drank castoreum” ended up being linked to by an NPR article in March 2014 on castoreum flavouring and the result was a huge spike in readership. That post has nearly 1200 views! I had a follow-up this year on castoreum as a driver for beaver hunting rather than just fur, but it’s popularity is nothing like the drinking post.

Muskox, the other main subject of this blog, has to be the worst named animal on the planet since it is neither an ox nor produces musk. Its name is certainly not the only thing contentious about it. It can be an inconvenient animal, especially when it crosses lines over national boundaries (like a herd did in the 1970s) or into urban areas, resulting in sanctioned culls. Financial compensation is often required when muskoxen have caused damage within ‘allowed’ areas. Reintroduction efforts are anything but cheap – in the case of the muskoxen, there was significant fundraising (the beaver reintroduction had required fundraising too).

The original motivations to bring the muskoxen to Norway and Svalbard were complicated and political, although practical considerations like its potential use as a meat source as an acclimatised animal were also fundamental. Patriotism and nationalism are key elements in reintroduction because there is often a sense that the animal should belong within a particular nationstate where it is currently absent. There remains the question, though, as to whether previously extinct animals will be counted as ‘citizens’, which often depends in turn on how lines in time are drawn by scientists. An animal’s history and the way in which that animal is remembered in the communal memory can also affect its acceptance–this applies even to introduced species that can become so accepted that they are state symbols. All of these cultural issues factor into how ‘attractive’ a reintroduction is, even if people think they are being ‘scientific’ about their decisions.

One of the most interesting muskox stories this year was the pair of muskoxen traded to China in exchange for a pair of pandas in 1972. Milton and Milton did not fare well in the Chinese zoo and soon died. It was a sad story, although it didn’t get as much attention as the death of Marius the giraffe in the Copenhagen zoo in February. That was likewise dwarfed by the media coverage of the 100th anniversary death of Martha, the last passenger pigeon, who was put on display at the Smithsonian. Of course, it’s not easy to know you’ve seen the last of a species, just as it is difficult to trace the beginning of an idea.

I included a fair share of other species on this blog in 2014 too, including the cultural history of vultures and cod, a suggestion to reintroduce wild reindeer as fodder for wolves, the relationship between American bison and Native American, and the amazing success of axolotls in captivity in spite of their near-extinction in the wild. Insects even made an appearance in posts about beaver beetle specimens and their missing data and parasite co-reintroduction. I was also interviewed for a feature article on responses to raccoon dogs entering Sweden that appeared in the magazine Filter in June.

I had noticed raccoon dogs in an exhibit case of ‘new species in Sweden’ at the Swedish Natural History Museum (Naturhistoriska Riksmuseum), which I think has missed out on telling possible species histories.The Natural History Museum in Brussels, however, was very good about giving animals personality and a voice, and the Field Museum in Chicago included some compelling animal histories. I always keep an eye out for reintroduced animals in exhibits, like the beavers at Oulu University’s exhibit on Finnish animals and in Lund University’s post-glacial fauna of Sweden exhibit. A visit to a parish school museum in Estonia even prompted me to write about beavers on school posters. A northern bald ibis, which is being reintroduced as a migratory bird between Germany and Italy, is being exhibited as part of the Welcome to the Anthropocene exhibit at the Deutches Museum in Munich.

The Welcome to the Anthropocene exhibit highlighted for me the problem of attempts to de-humanise thoroughly human landscapes, especially when humans are treated as ‘unnatural’ in restoration and rewilding discourse. A similar thing happens with deextinction talk that seems to overlook the social and cultural barriers to actually reintroducing previously long-dead species. We have the power to envision wilder worlds, but only if we make humans visible in environmental issues as integrated parts of the Earth.

Over the course of 59 blog posts, that’s what I was thinking through in 2014. None were final thoughts–they are always works in progress. By writing them here I get to work thorough my ideas while sharing them out loud, if you will. I hope it has been as interesting to read (I had over 10,000 page views this year) as it has been to write. I’m looking forward to continuing my journey in 2015 as I explore what reintroduction has meant in the past and what it could mean in the future.