In search for the Golden Fleece

I ran across a lovely poem by the modernist poet Marianne Moore (1887-1972) this week titled “The Arctic Ox (or Goat)”, published originally in her collection O to be a Dragon (1959). Here is an excerpt:

To wear the arctic fox

you have to kill it. Wear

qiviut–the underwool of the arctic ox–

pulled off it like a sweater;

your coat is warm; your conscience, better.I would like a suit of

qiviut, so light I did not

know I had it on; and in the

course of time, another

since I had not had to murderthe “goat” that grew the fleece

that made the first. The musk ox

has no musk and it is not an ox–

illiterate epithet.

Bury your nose in one when wet.…

Lying in an exposed spot,

basking in the blizzard,

these ponderosos could dominate

the rare-hairs market in Kashan and yet

you could not have a choicer pet.They join you as you work;

love jumping in and out of holes,

play in water with the children,

learn fast, know their names,

will open gates and invent games.…

If you fear that you are

reading an advertisement,

you are. If we can’t be cordial

to these creatures’ fleece,

I think that we deserve to freeze.

She wrote “The Arctic Ox (or Goat)” based on an article written by John J. Teal, Jr. titled “Golden Fleece of the Arctic” published in the March 1958 issue of Atlantic Monthly. Teal was the major proponent of muskox domestication in the US from the 1950s to 1980s. He had an interesting longstanding relationship with the muskoxen in Norway.

In the early 1950s, he looked to Adolf Hoel’s work importing muskoxen to the Norwegian Dovre Mountains as an example to follow in muskox domestication. He wrote an article “The Norwegian Musk-Ox Experiment” published in The American-Scandinavian Review in spring 1954 extolling the “important information … regarding their feeding habits, sicknesses, and peculiarities” coming from John Angård who took care of the calves destined for release. Teal was encouraged by “the Norwegian experiment” and was eager to use it as the basis for his new muskox domestication project. Although the Norwegians never framed the Dovre releases as ‘domestication’, the knowledge they produced was repurposed by Teal.

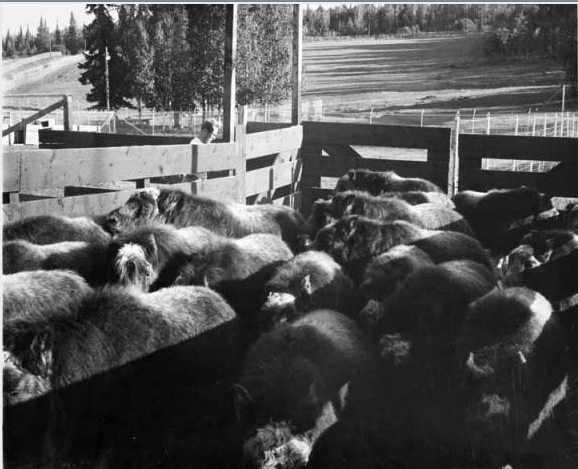

In 1954, Teal captured some muskox calves in the Thelon Refuge of Canada and relocated them to a farm in Vermont working as the Institute of Northern Agricultural Research. His vision was that the animal would be “useful not only for Arctic husbandry but also for the many sub-marginal farming areas in our northern states” (quote from “The Norwegian Musk-Ox Experiment”). In 1964, Teal decided to move his project to Alaska and founded a farm at the University of Alaska Fairbanks using animals captured on Nunivak Island (I discussed these animals previously here). He set up the Oomingmak Musk Ox Producer’s Cooperative to knit the wool in 1969.

Because of his extensive experience working with muskoxen in domestic settings, when Norwegians began floating the idea of setting up a muskox farm in northern Norway, they called on Teal’s expertise. In 1966, he visited Tromsø and the little town of Bardu to discuss the idea of importing some of his animals to northern Norway.

(An aside about how global this all is: The calves caught in East Greenland had been shipped to Norway in 1929 then sold to the US in 1930 and shipped via boat then train to Fairbanks. In 1936, the animals were relocated to Nunivak Island. In 1964, calves caught on Nunivak were taken to Teal’s farm. Now, the idea was to take calves from Teal’s farm back to Tromsø, Norway. My head is spinning…)

Anyway, the import from Alaska ended up not being practical, so the Norwegians went to East Greenland (the source population) instead. Teal continued to play a critical part in the plans for domesticating muskox in Norway. The veterinarian who prepared an official report for the Norwegian Parliament about the suitability of muskox as domestic animals visited Teal’s Alaska operation in 1968. In 1969, Teal once again visited Tromsø as an expert consultant and he became the official advisor to the farm set up by Norsk Moskus A/S. One newspaper account even called Teal “the father of the idea [of muskox domestication] here in Norway.” (Aftenposten, 28 Nov 1970). I would agree that he was a booster and expert, but father of the idea is stretching a bit. Instead, what we see is a circular, self-reinforcing relationship: Teal looks to Hoel and the Norwegian import as example, Teal sets up farm in Vermont then Alaska, then Norwegian interests in northern Norway look to Teal as example.

When Marianne Moore wrote her poem, she bought into Teal’s boosterism. Muskox wool (qiviut) was the miracle fibre that would dominate the winter fabric market. Muskoxen were tame, easily playing side by side with children. These characteristic ended up being proven untrue. Teal’s farm was indeed successful–on a small artisanal scale–and it remains so to this day, selling products through the cooperative. But qiviut never became a household item. The northern Norwegian domestication attempt folded in the 1980s. While you can buy qiviut mittens at the muskox breeding center in Tännäs, Sweden, this is not its main business. Being cordial toward muskox fleece, as Moore implied, turns out to not be enough.