Pamir the Przewalski and his places

When I was at the Ménagerie in Paris, which is part of the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle, I found a lovely children’s book in the gift shop: L’histoire vraie de Pamir, le cheval de Przewalski. The book (which you can buy here), written by Fred Bernard and illustrated by Julie Faulques, is a real reintroduction story.

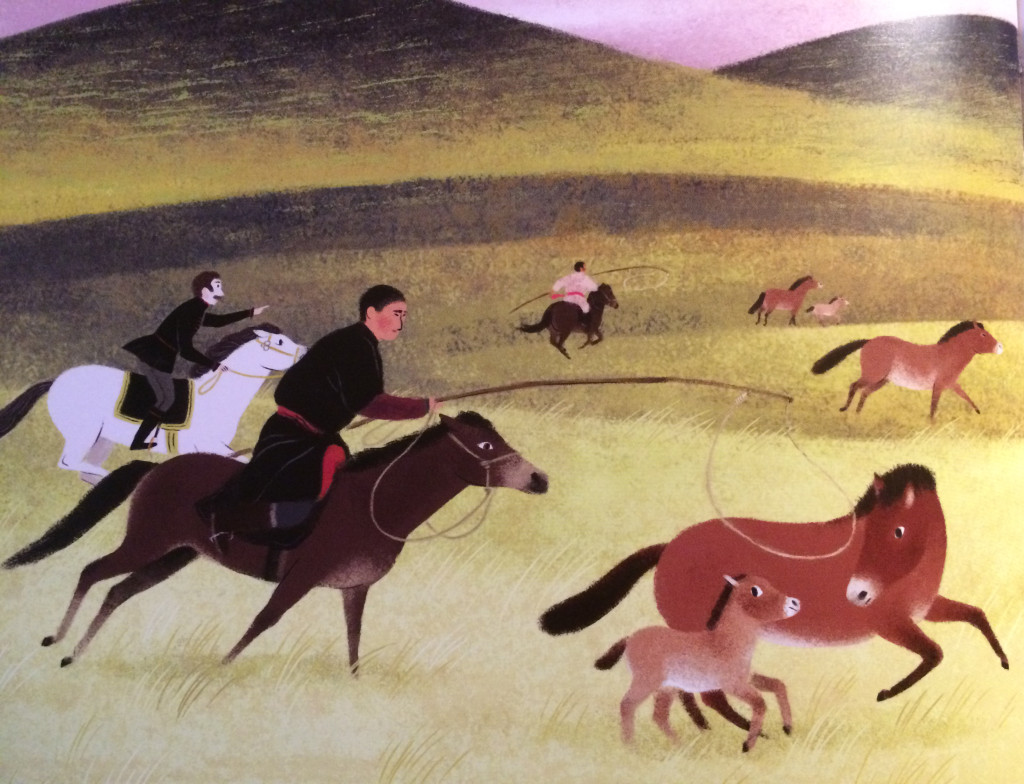

The book begins by backing up in time to present the Przewalski horse as living on the steppes of Mongolia. The Przewalskis were wild, untamable horses, killed as prey by Mongols on the backs of domestic horses. Then the horses are discovered by a colonel named Przewalski in the 19th century. After the discovery scene, the text presents the capture of Przewalski horses which were shipped to zoos “in order to save the species.”

Some of the 50 horses captured at the turn of the 20th century were shipped to the Ménagerie in Paris. And now we get to Pamir, who was born in the zoo and is the great-great-great-great-great-grandson of animals caught in the wild.

After the Przewalski horses were captured, the species became extinct in the wild. But the zoo populations were carefully bred and grew in numbers, from 13 founding population animals to over 1000. In 1993, when a scientific reintroduction project was begun, the two-year-old stallion Pamir was selected for the program. He was released into a large enclosure on the Méjean Plateau in France along with horses from other zoo collections. The horses had to adapt to wild living, including finding their own food sources and reproducing freely within the herd. In 2003-4, 22 horses were then taken to Mongolia and reintroduced in their prior range — some of these were Pamir’s descendants.

It’s a beautifully illustrated book with a positive story. But as a historian thinking about belonging and reintroduction, a couple of things struck me.

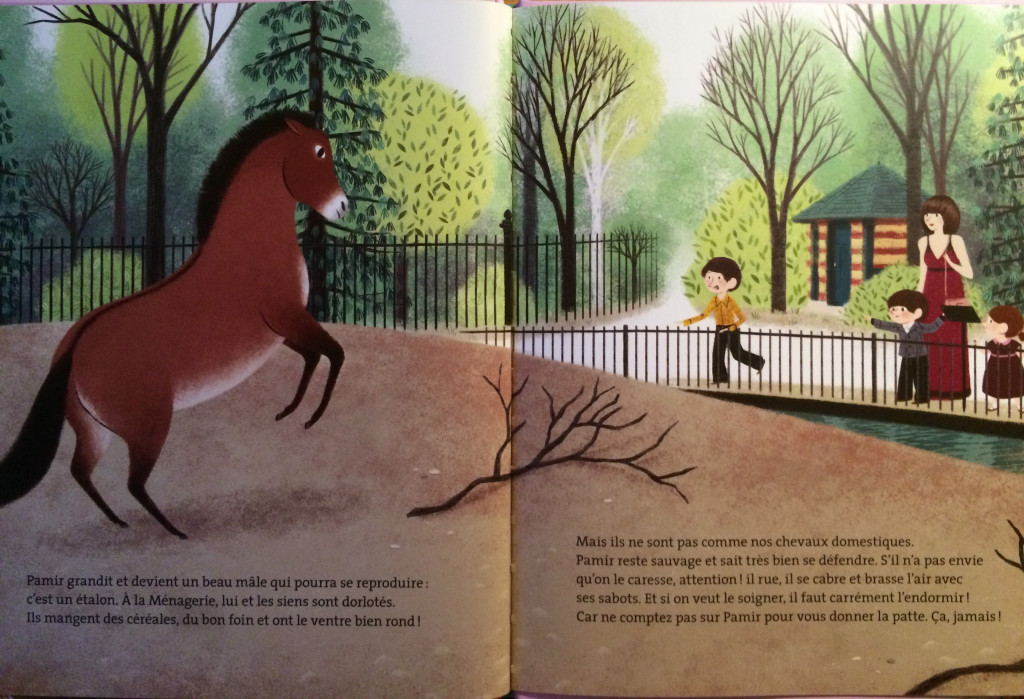

First, there is a claim about the role of France as place in the story. While the book places the Przewalski horse in Asia, one page is dedicated to the horses in the caves of Lascaux in France. “The small horses have a remarkable resemblance to Pamir,” which is an ingenious way of linking this Asian species to France where the Pamir story takes place. The place of the Ménagerie zoo also matters in the story because it was here that Pamir was born — three double page scenes show him in his zoo enclosure. Placing Pamir specifically in Paris makes him all the more real and important to the French children.

Second, there is a continual insistence on the “wildness” of the Przewalski horse. They are “chevaux sauvages” of the plains. When Mongols tried to domesticate them “c’est impossible!” Although the image shows Pamir in the zoo, the text stresses “Pamir remains wild and very well knows how to defend himself. If he does not feel like a caress, beware!”. He moves to the enclosure to be prepared for “la vie sauvage”. It is through the reintroduction of the Przewalski horse after 100 years in zoos that we proved “it is possible to return an animal to the wild who had not previously known it.”

These are not unusual claims: everyone talks and writes about the Przewalski horse as “the last wild horse”, meaning specifically the last undomesticated horse. But I have to wonder how true that claim can be. The horses eventually reintroduced into Mongolia were descendants through many generations of animals that had only ever lived in zoos and were purposefully bred in extremely controlled ways. The stud books of the horse were carefully recorded and managed. Moreover, the horses were bred to look a particular way.

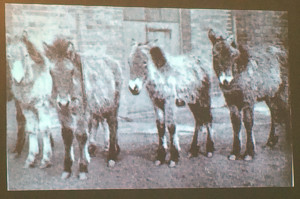

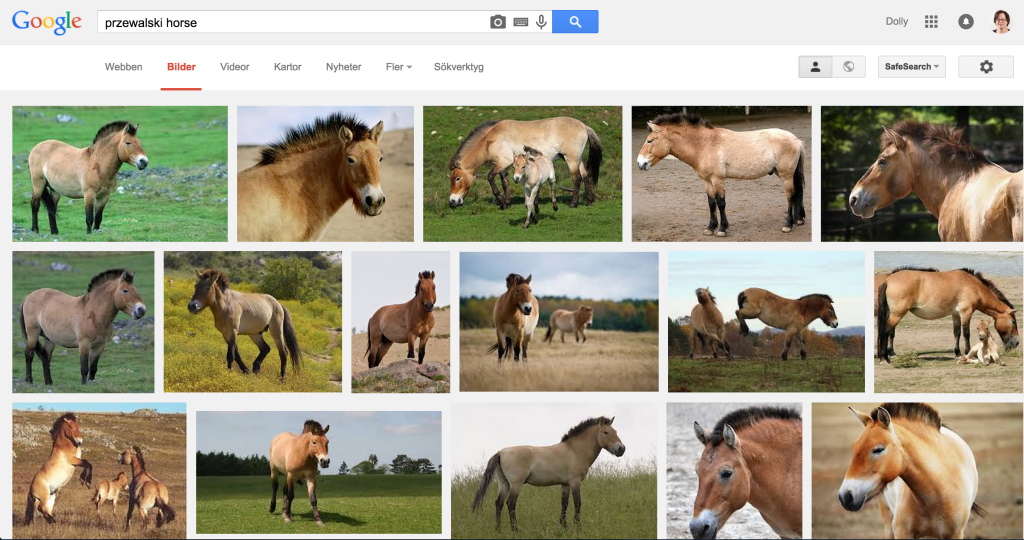

Nigel Rothfels at the American Society for Environmental History meeting in March 2015. He showed a picture of four of the scraggly horses originally from Mongolia, which we can compare to the images of Przewalski horses today which shows extremely consistent animals. (See also another photo taken before 1901 of a captured animal)

Visual consistency is a trademark sign of intentional breeding. Kate Christen of the Smithsonian Conservation Biology Institute also discussed this in a paper at the World Congress of Environmental History in 2014, noting that Przewalski breeding was conducted to produce offspring “conforming to their European handlers’ imagined preconceptions about wild, primitive horses such as those in the cave paintings.” If domestic animal implies one bred for a specific purpose, these horses are no less domestic than fjord horses or shires or shetland ponies. The claim of wildness is a rhetorical one to place this horse as belonging on the Mongolian steppes.

So Pamir is a story about how an animal can belong in two places at once. Reintroduction causes a shift of physically belonging from one place to another, but the ontological belonging to both places remains.

One Comment

Laura Pajot

So, the dun horse of the steppe’s were not all the same color and markings when they first were captured and the remaining horses died out in the wild! I always learn such amazing things from your blog! I wonder what the colors and markings were on the original horses. Hard to tell from black and white photos, but the dark ones could be almost bay. I can’t remember off the top of my head what dun genetics are in horses, but I think it’s bay or black with another allele that overrides the darker color, I think…. darn I hate having fibro with what it does to my brain!