A historian walks through the beaver’s homeland

In historical work, we are called on to imagine ourselves in another time and another place. We try to see the world as the people (or animals) in our stories would have seen it. That’s not always an easy task. But because I was lucky enough to spend the last two days in southern Norway in the homeland of the Scandinavian beaver, it’s now a little easier for me as I write the beaver reintroduction story.

Yesterday I walked around the property at Næs Ironworks, which is now a museum featuring the double blast furnace, water-powered hammering shop, and templates for cast iron stoves. It was a lovely clear day for a stroll with my guide Gunnar Molden. Gunnar told me all about the Aall family who became the mill’s proprietors after Jacob Aall purchased it in 1799. Jacob was supposed to become a priest, but opted instead to travel around Europe to learn the iron working trade. When his father (who had been the one pushing him into church service) died, Jacob decided to purchase this iron mill in the Norwegian countryside. Jacob would go on to become well-known for his involvement in Norwegian independence from Denmark in 1814.

Unlike most mill owners who continued to live in the big cities, Jacob and his wife Lovisa moved to a stately home on the Næs property. Lovisa worked to create a gentile estate, including making a romantic park in the English garden style with an artificial pond and gazebo. The pond was on some line between wild and tame, natural and artificial. Walking through the grounds let get a sense of what it would have been like to have this as my backyard, which is what it would have been for Nicolai, the oldest son of Jacob and Lovisa.

The setting matters because Nicolai Aall would go on to become the owner of the ironworks in 1844, and some time after that, he banned all hunting of beavers on Næs property. At this point, I have not found a concrete reason why he did it, but several things about his background give us hints. Growing up on this property would have certainly encouraged him to appreciate nature. Although he formally studied mineralogy at the university, he developed a passion for zoology. He collected zoological books and amassed an impressive collection of insects and birds, as well as mammals. He was also an avid hunter and employed a taxidermist on his staff. So at some point he decided that beavers were getting too rare as hunted prey and they needed protection. It is said that this protection is the only thing that kept the beaver in Norway from going extinct like the beaver in Sweden.

Today as I drove from Arendal on the coast up into the mountains to visit the Elvarheim museum in Åmli, I understood why beaver would have survived in Åmli long enough to be protected by Nicolai Aall. With mixed deciduous-coniferous forest rising up on the hills, there were small, still lakes around every bend — the perfect kind of lakes for beavers. I’m sure plenty of beavers now inhabit the waters I drove by, and I’m sure they did 100 years ago as well.

I met Tonje Ramse Trædal at the Elvarheim museum, which was founded from a hunter’s huge collection of taxidermy specimens and hunting/trapping gear. Just this June they opened a brand new beaver exhibit, which includes both fabulous displays about beaver ecosystems and some local information about the role of Åmli in populating the beavers of Europe. All of the beavers reintroduced to Sweden in the 1920s and 1930s came from this little town.

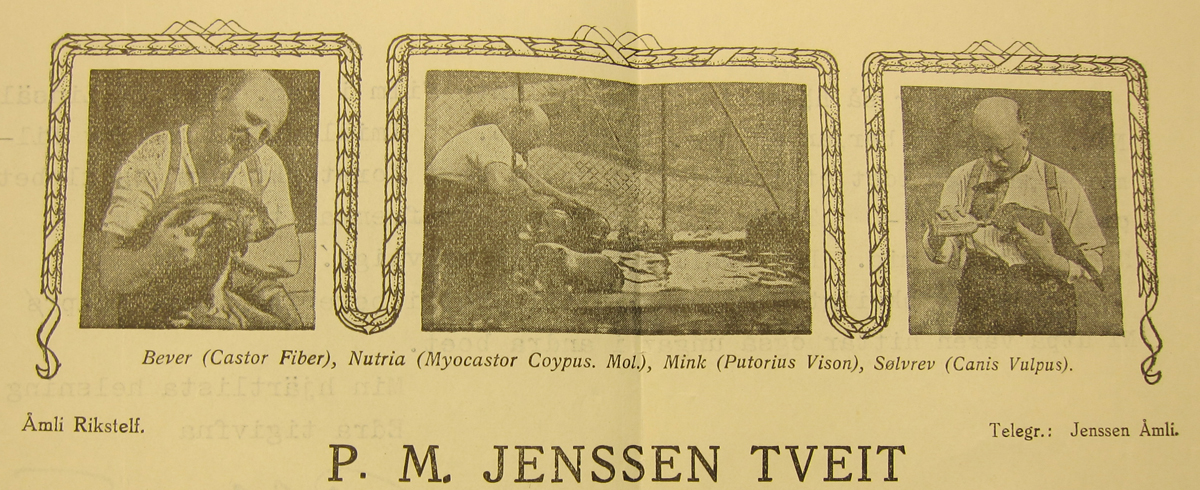

More specifically they went through the hands of Peder Martinius Jensen Tveit, “Bever Jensen”. So it was a treat to take a car ride with Tonje to Tveit, a few kilometers up the hill from Åmli, to see the Jensen farm. What was fascinating was that Jensen’s property, called Austigard, is adjacent to a farm named Bakkane, which was owned by Sigvald Salvesen. Sigvald was the Jensen’s main competitor in the live beaver business and from the tone of some documents I saw today, there was no love lost between them. Looking out past Jensen’s property to Salvesen’s, which would be no more than a few minutes to walk, it made the language in the documents all the more real. I could ‘hear’ the men complaining about each other.

Historians often work behind a desk. It might be in an archive, a library, or an office. It might be looking at digital files, hand written letters, or artwork. But more often than not it is divorced from the place of the history. This trip reminded me that it’s both insightful and refreshing to get out in the fresh air and see where history took place.

One Comment

Pingback: