Explorers and muskoxen

I visited the American Museum of Natural History in New York yesterday. They have an excellent series of dioramas in the Hall of North American Mammals, which were originally opened in 1943 and elegantly restored in 2011-12.

One of the dioramas features muskoxen from Ellesmere Island, the third largest island in Canada. The pair were killed by Robert Peary’s Arctic expedition in 1898. This was the first of Robert Perry’s series of expeditions attempting to reach the North Pole (1898-1902, 1905-6, 1908-9) — he claimed to have finally gotten there on the last of those expeditions.

The diorama is framed in terms of Arctic exploration. The sign places the scene at ‘The Bellows’, a Canadian high Arctic valley on Ellesmere Island named by a British expedition team in 1875. The name was chosen because of the valley’s ‘unrelenting winds’. Within this context of exploration, the muskox is claimed to have been critical to the survival of early Arctic explorers like Peary:

Although sometimes musky in taste, musk-ox meat was vital to the survival of many Arctic explorers. Fresh meat supplies some vitamin C, necessary to ward off scurvy. During the British Arctic Expedition of 1875, fresh game was often scarce–and so scurvy debilitated half the crew.

This is true enough, but what the sign doesn’t tell you is that muskoxen like these were much more important as food for dogs than people.

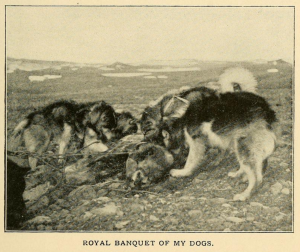

Peary was one of the great dog sledders. His book Northward over the ‘Great Ice’ about his earlier expeditions in Greenland, 1886 and 1891-96, contains detailed descriptions of muskoxen hunts. Although the men consumed some of the muskox meat, it was primarily for the dogs, which he called his “faithful shadows”. Peter Lent (Muskoxen and their Hunters) estimated that Peary’s 1898-1900 expedition on Ellesmere took at least 180 muskoxen. Considering that a dog sled team needs something around 9-10kg of meat a day, most of the muskox meat was consumed by the dogs. Hunts for muskoxen were thus as motivated by the needs of the dogs as they were the needs of the humans:

With the utmost eagerness we scanned every new prospect for the coveted animals; for we knew that musk-oxen meant fresh meat for ourselves, and an abundant supply of food for our dogs. (332-33)

While hunting animals in order to provide human food might be more palatable than realising that hundreds of muskoxen became dog food, the sign at AMNH misses an important aspect of the story: the muskoxen of Ellesmere, Arctic explorers like Peary, and the sled dogs which powered the exploration were tied up into one history. The multispecies entanglements of the Arctic explorations should not be forgotten.