Animals and authority in the Arctic

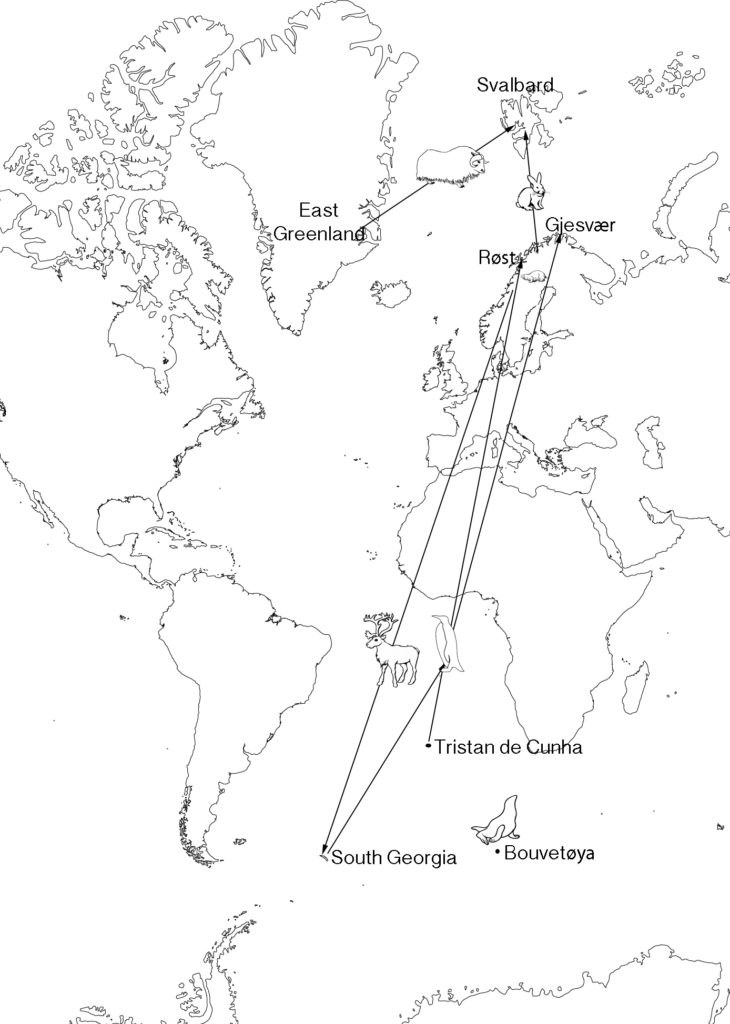

I have a new article out co-authored with Peder Roberts (KTH Royal Institute of Technology) on the many attempts and plans by Norwegians to move animals to and from the Arctic during the Interwar period. We teamed up together on this because while I had looked into the muskoxen relocated from East Greenland to Svalbard and the plans to introduce lemmings and rabbits as fox food on Svalbard, Peder had done work on penguin, seal, and reindeer relocations involving the Antarctic. The sheer number of these attempts was mind boggling.

These animal translocations were no easy task. The distances were amazing, especially given the speed of transportation at the time. Special concessions had to be made to transport the animals. Muskoxen needed to be boxed; the penguins had a little pool to swim in on their ship (see the cute pictures: the group, with onlookers, and being fed).

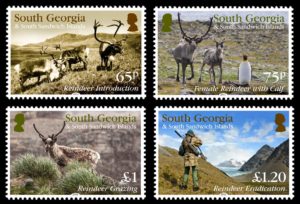

The animals themselves also had to adjust to their new surroundings once they got there. Although the habitat may have been similar on some level, changing between northern and southern hemisphere with its flip-flopped seasons couldn’t have been easy on the reindeer or penguins. Although the penguins were not able to establish a colony, the reindeer were very successful and it was not until this year that they were exterminated from the island of South Georgia.

Our big question was why: why had people decided to move these animals around? Although all of the movements were ostensibly about improving natural resources, particularly meat availability, we believed there was something more philosophical in the relocations. We argued that moving polar fauna was a key aspect in Norway’s efforts to legitimize its status as a polar nation. The transfer of polar animals was a central aspect of ishavsimperialisme (polar imperialism) of the 1920s and 1930s. Moving these animals around marked both where they came from and where they went to as Norwegian. In the high stakes game of international diplomacy, outward signs of territorial claims functioned rhetorically as authority statements. This was important for claiming sovereignty over whaling stations in the Antarctic which had been primarily British, hunting territories in East Greenland which were being contested with Denmark, and Svalbard which was a free-for-all landgrab. The animals served as geopolitical markers: the claim was that the animals and the places they lived belonged to Norway.

Our article “Animals as instruments of Norwegian imperial authority in the interwar Arctic” is published in a new Open Access journal for environmental history, Journal for the History of Environment and Society, which means that you can read the whole article for free.