A non-specialist specialist

This week I’m at the 12th European Multicolloquium of Parasitology (EMOP XII) in Turku, Finland. Why, you might ask, am I at a conference about parasites? I am not by any stretch a parasite specialist like the rest of the attendees. But I was asked to give a plenary speech in spite of, or even more correctly because of, my background. I think how this came about can be instructive for environmental historians so I’ll tell you the story.

Back in the first year of this blog, I wrote about a chance find I had made: a mention at the top of Beaver Jensen’s letterhead of beaver beetles (Platypsyllus castoris). The find inspired me to do some research about this ectoparasite (that’s a parasite that lives on the skin) of beavers, how it was discovered, and why Jensen would have been selling it. I even visited the Naturhistoriska riksmuseet in Stockholm and got to see some very small beaver beetles collected from the beavers held in Skansen in 1923 before they were reintroduced in northern Sweden.

While I still need to get my beaver beetle story published in some form, I did publish a review-type article in the major journal Conservation Biology that took a broad look at parasite co-reintroduction (you can read the unformatted text for free here) . It was this article that the organisers of EMOPXII had read.

When I was contacted by one of the EMOPXII organisers, Antti Oksanen, inviting me to come to the EMOP event, he made a point to mention that he read my CB article and was impressed with it. But my background outside of the standard parasitology community was a specific draw — Antti told me that they wanted to get people as plenary speakers with different perspectives. I accepted the invitation, because these are exactly the type of people I was trying to reach with my article: the scientific community working with parasites and conservation projects like reintroduction.

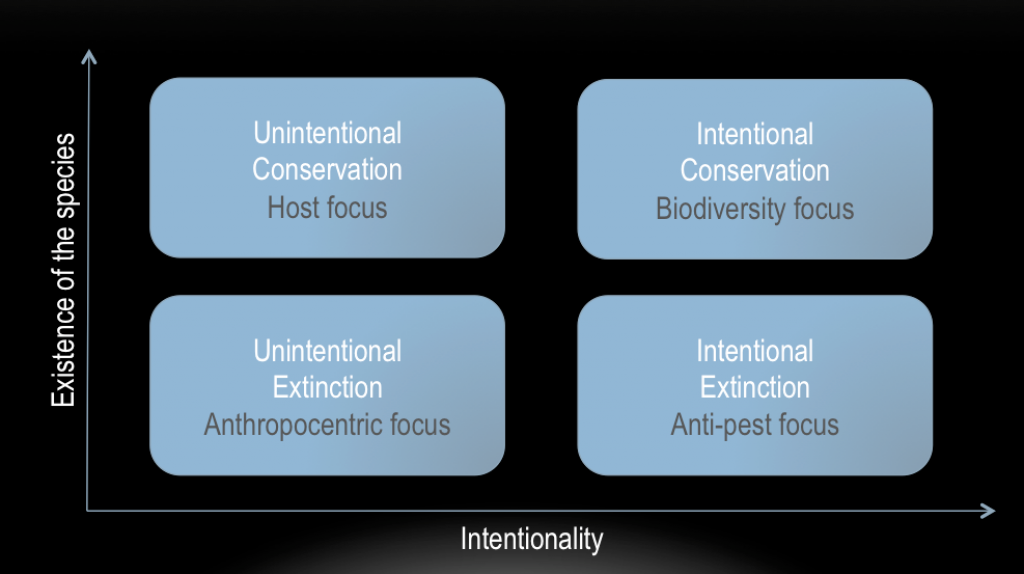

Tomorrow I’m giving my talk “Are Parasites Forever?”, which is a twist the conference theme “Parasites forever”. I’ll be laying out four potential outcomes for the parasite species which I will argue are based on historical social context of the human-parasite relationship and the human attitudes toward the host and parasite.

I’m still using ectoparasite examples, like in my earlier paper, but I’m expanding on the historical social context. This is, of course, what historians are specialists in. Environmental historians are particularly interested in the relations between humans and the non-human world—how those relations are structured and why those structures exist. In other words, historians want to understand why we end up with certain outcomes rather than just saying that we do, as is the typical natural science approach. Environmental historians are better equipped to uncover why certain choices were made and why particular attitudes toward parasites have existed (and still do).

The lesson of my EMOP experience for environmental historians should be that we with our own speciality have something to offer the natural scientists. But we have to work to publish in the outlets that natural scientists read. If we only stick to our disciplinary boundaries and write only for other historians, then that is the only audience that will read our work. Historians have to be willing to talk with scientists in their forums and tell them stories that they can understand and relate to, like the beaver beetle’s return home on the back of reintroduced beavers.