On the last of the tigers

This September 7th marks the 80th anniversary of the extinction of the thylacine, also known as the Tasmanian tiger. Or at least, that’s the date that has been agreed upon in official sources as the extinction date.

I took up the issue of dating the thylacine’s extinction in my recently published article “Presence of absence, absence of presence, and extinction narratives” in the volume Nature, Temporality and Environmental Management: Scandinavian and Australian Perspectives on Landscapes and Peoples. The question is whether or not the absence of evidence of live thylacines should be interpreted as the absence of thylacines. This proves a more challenging question to answer than you might think.

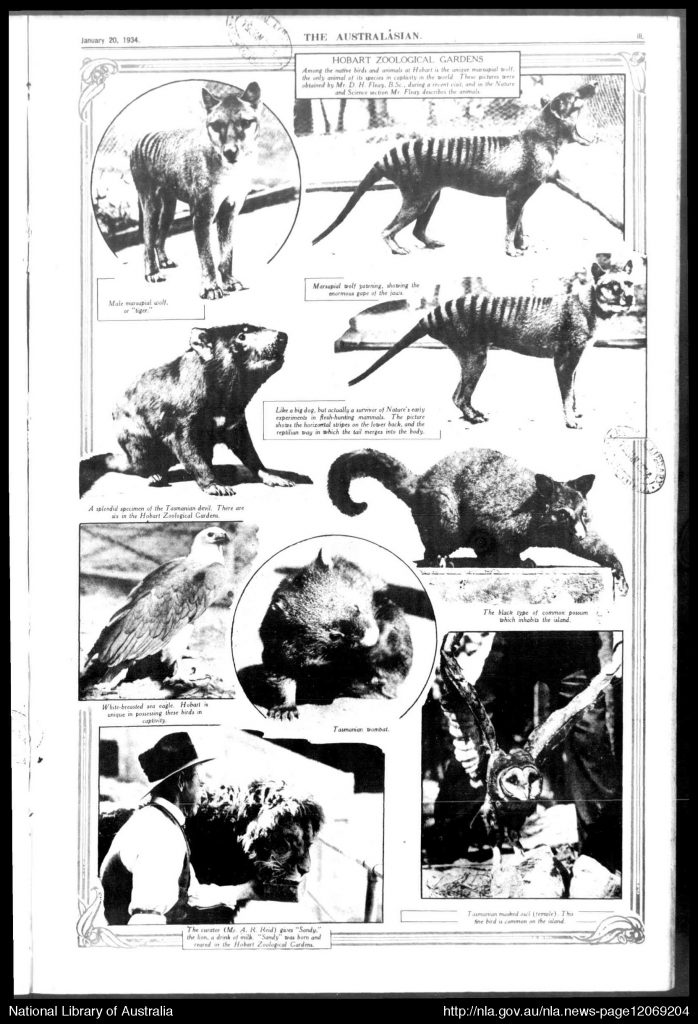

The last confirmed thylacine died on 7 September 1936 in the Beaumaris zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. The Australasian newspaper of Melbourne had published photos of that particular thylacine two years before for an article about the zoo in Hobart. It was the last time a live thylacine was captured on film.

But, deciding those photos represent ‘the last’ thylacine is in retrospect.

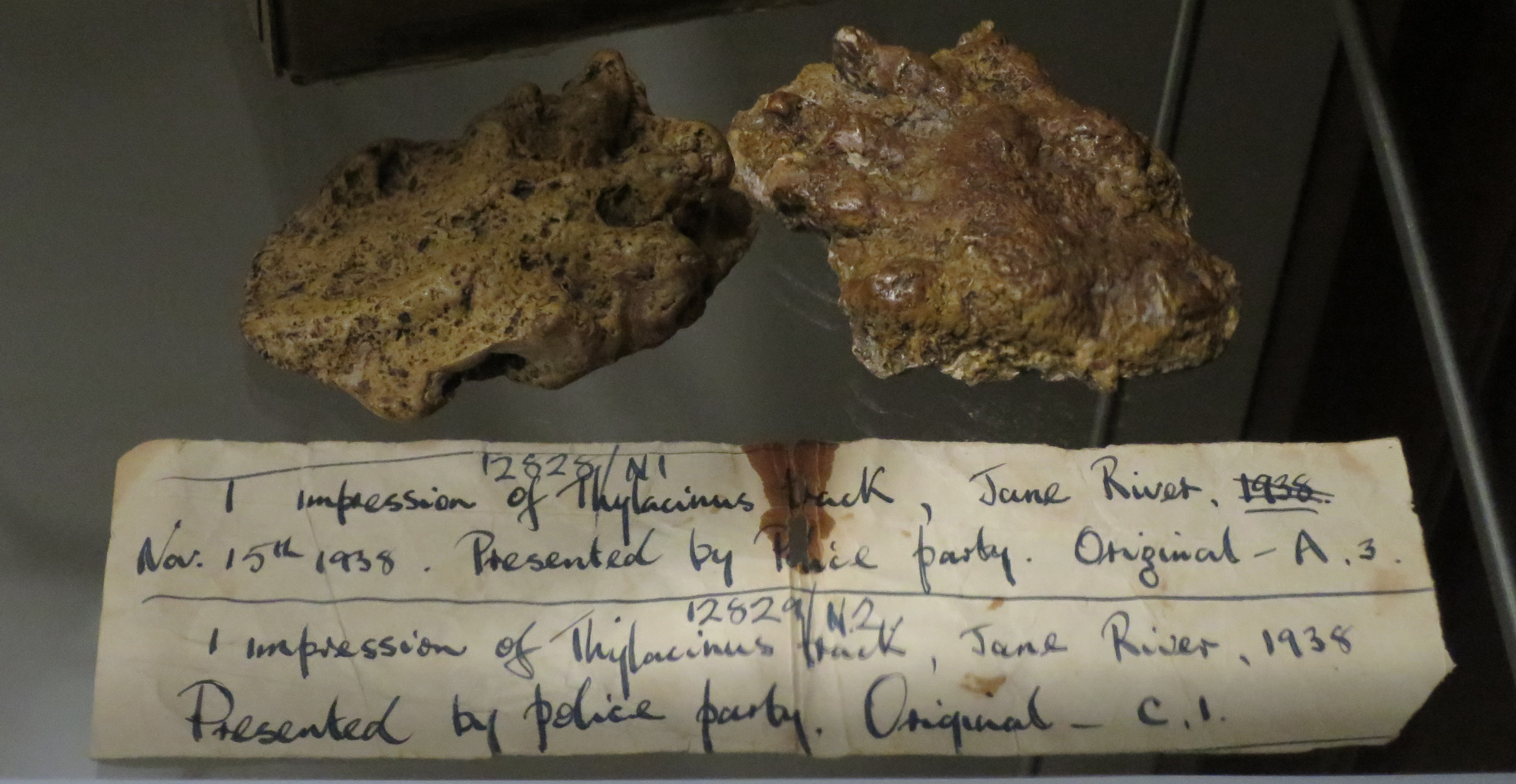

In 1936, most people accepted that the thylacine numbers had been radically declining, but few thought the animal was extinct. The Tasmanian Animals and Birds’ Protection Board (TABPB, later to become the National Parks Service) organised an expedition to count the thylacines in the mountainous region in 1938 and published a report of that search in 1939. The report included photographs of the team members making plaster of paris casts of thylacine footprints, as well as recording other evidence of thylacine presence. No thylacines themselves, however, were spotted. This did not deter the expedition leader Michael Sharland from believing that the species still survived:

It must be emphasised, however, that its failure to reveal itself more frequently is not necessarily indicative of approaching extinction. Great areas of this game country are devoid of human inhabitants, while others are only sparsely inhabited.

The sentiment that the thylacines were still out there somewhere–we were just looking in the wrong places–continued long after this. In the article, I wrote about some of the many searches to find thylacines, including one in 1980 organised by World Wildlife Fund and another in 1984 prompted by the media magnate Ted Turner offering $100,000 for a proven thylacine sighting. None of these expeditions turned up what was considered scientifically credible evidence of the thylacine’s continued existence. Yet, sightings continued to be regularly reported in local newspapers. The failure to have scientific confirmation has not deterred the belief of many that the thylacine is out there.

The thylacine was officially declared extinct by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) in 1982 and by the Tasmanian government in 1986. In these declarations, the absence of presence was declared as a presence of absence. In 1996, Australia established National Threatened Species Day on September 7th to commemorate the 60th anniversary of the death of the Hobart thylacine. This made the narrative of extinction official: 7 September 1936 was the end of the thylacine.

The importance of the death of the thylacine in the Hobart zoo was recognised only in retrospect. It was only when no more could be found after years and years of looking that the date of the tiger’s extinction was set.

So I am left wondering how someone in 80 years from now will look back on the extinctions going on all around us in 2016. How many things that we do not have on our lists now will be on the lists then with dates of extinction before 2016? Will people still remember the thylacine at its 160th extinction anniversary — or will it be reduced in importance as just one of many recent extinctions?

One Comment

dolly

This blog post was republished with a few additions at the Washington Post: https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/animalia/wp/2016/09/07/the-tasmanian-tiger-went-extinct-80-years-ago-today-but-that-took-decades-to-figure-out