Kobras and national stories

I was reminded yesterday during a visit the Sagadi Forest Museum, part of the Estonian State Forest Management Centre, that beaver reintroduction has a wide and long Europe history. The museum — which had a wonderfully designed gallery featuring videos, modern & historical photography, and artefacts set within tree trunks that made it feel like you were walking through a forest — integrated beavers (kobras in Estonian) in several places.

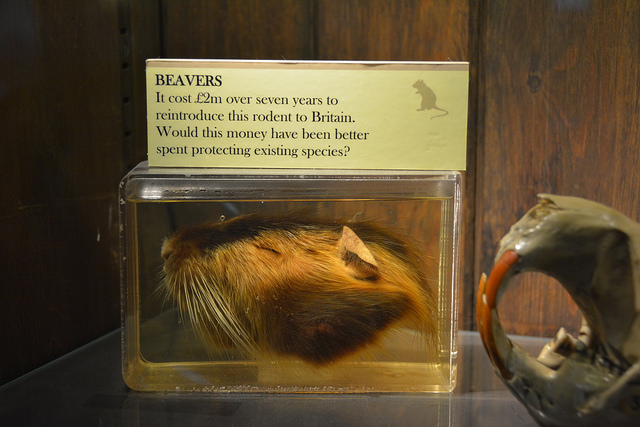

A pair of stuffed beavers gaze at each other and their handiwork in one section of the exhibit about the Estonian forest ecosystem. Beavers were featured in the displays about aspens, willows, and hazel as consumers of twigs and barks from those trees. Here, the beaver seems to be a ‘natural’ and ever-present part of the Estonian forest.

But upstairs, in the section on hunting, the visitor learns a bit more about the real story of beavers in Estonia. Archeological evidence indicates that beaver was extremely common prey: in finds from the northern Estonia area dated to 4000 BC, 26% of all the bones belonged to beaver. Evidence from the 13th century indicates that moose and beaver were the primary hunting objects. In the hunting timeline, we learn that the last beaver in Estonia was killed in 1841 (that’s 30 years before they disappeared from Sweden). In 1957, they were reintroduced. And they’ve had a recovery similar to Sweden. In 2007, the beaver population in this small country was estimated at 18,600, and 6,083 beavers were killed that year. Castoreum is the main beaver product – I even bought a soap scented with castoreum at the museum shop!

At my keynote on Tuesday, one of the questions from an audience member had to do with the word ‘extinction’ and whether or not is was appropriate for me to use the phase ‘beavers were extinct from Sweden’ in 1871. After all, he said, European beavers as a species obviously weren’t extinct, since some of the beavers in Norway were used for reintroduction later; maybe beaver weren’t within Swedish borders, but they weren’t extinct. My answer was: whether or not the beaver was still non-extinct in another geopolitical entity didn’t matter to the historical actors in my story — the people writing about the beaver in Sweden were only concerned about its presence or absence in Sweden. Extinction for them had to do with geopolitical boundaries more than biological ones.

This exhibit in Estonia reinforced my answer. Estonians tell the story of beavers in Estonia – when they died out and when they came back – without taking into account the complex issues of being part of various nations in the 20th century (Russia, Soviet Union, Germany, and as a Republic) and the geographical connections to the other Baltic countries (Lithuania and Latvia). The ‘national’ is the framework within which extinction and reintroduction took place, and still takes place through public education and museums.