Naming and claiming the last

In April 1996, two men working at a convalescent center wrote a letter to the journal Nature proposing that a new word be adopted to designate a person or individual of a species that is the last in the lineage: endling. This had come up because of patients who were dying and thought of themselves as the last of their lineage. The suggestion of endling was met with counter-suggestions in the May 23rd issue of Nature: ender (Chaucer used it to mean he that puts an end to anything), terminarch (because it has a more positive ring than endling which sounds pathetic according to the respondent), and relict (which means last remaining, but typically for a group).

Nothing more appears to have been made of the suggestion or the word in scientific circles. Endling doesn’t show up at all if you search the Web of Science and it doesn’t appear in any English dictionary as far I was able to find. It has, however, made it into Wikipedia, which is why I got curious about where the word came from.

River area of Tasmania, about 1930. National Museum of Australia collection.

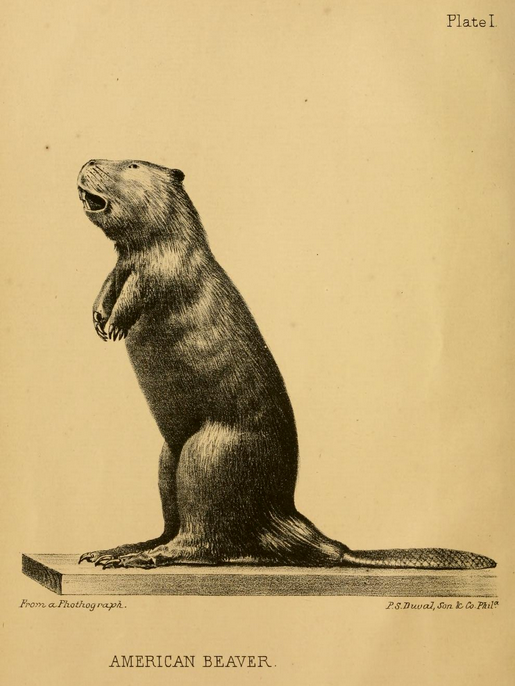

It turns out that the word gets a boost from down under. In 2001, when the National Museum of Australia (NMA) opened its doors, it featured a gallery called Tangled Destinies (now called Old New Land) and endling reappeared. Two thylacine specimens were put on exhibit: one a formalin-preserved body and the other a skin. On the wall above the case was written: Endling (n.) The last surviving individual of a species of animal or plant, according to a review I read of the exhibit (the reviewer mentions that the definition came from Nature). The exhibited skin of the thylacine might have been from the last wild thylacine (it was certainly one of the last in any case). The animal had been trapped by Charles Selby Wilson in 1930 and after the skin had in the Wilson family home for years, it was sold and appeared at the opening of the Cascade Brewery in Hobart because of the company’s trademark of a thylacine. When the Museum’s National Historical Collection was asked to purchase the skin in 1999, it was controversial, but in the end, it was decided that the skin had a social history worth telling (see Robin 2009). The exhibit also featured a video of the last thylacine, Benjamin, who lived its last days at the Hobart Zoo. [You can see other videos on the Thylacine Museum website too.]

What’s fascinating about this is that the museum staff took the endling concept and made it real. They wrote the definition on the wall as if that definition was official: it is written as if it was copied from a dictionary complete with the part of speech designation as a noun, yet I’ve found no Australian dictionary (or any other) that defines endling. And the definition the museum exhibit used is not exactly what the original Nature letter had defined endling as. Yet there it was in black and white defined. The word had been claimed. But what had it named? Was endling the last wild thylacine (represented by the skin) or the last thylacine ever (Benjamin)? That’s not entirely clear.

Endling seem to have caught on a little in Australia and I think it must be attributable to the exhibit which received a fair amount of notoriety. First, the writer Michael Barry chose the title “The Endling” for his science fiction short story in the collection Agog! Fantastic Fiction from 2002. In the story, a robot called the Endling is the last of his kind. Just before he expires, the Endling tells a young slave boy: “Remember, everything dies. Every species must have its Endling.” The end is inevitable, perhaps even welcome after you’ve seen all that the Endling has seen.

Then, Symphony Australia commissioned the composer Andrew Schultz to write a symphony titled Endling for the Tasmanian Symphony Orchestra in 2006. Since Tasmania was the home of the thylacine (tasmanian tiger), you see the connection. The orchestra performed the work in 2007 and you can hear two excerpts: Excerpt 1 and Excerpt 2. In the composer’s words,

This piece flows from a feeling of immense regret and sorrow about all that has been lost from the face of the earth. Beautifully adapted plants, animals and societies that are no more and have been replaced by what? A world of ugliness, material obsession, perpetual and pointless change, and the hideous “marketing” of everything from a symphony to a child’s smile. And we are all utterly caught up in it, in the postGod world, where even repudiation is another category fit for commercial exploitation. There is only a stoic solitude – the resignation of the endling – and the pure core of human experience to sustain us.

Just as Barry described his Endling as resigned to the fact that the end must come, so Schultz likewise found only stoic solitude an appropriate response to environmental loss.

After this, a Wikipedia page was created on 25 November 2007 which defines endling as “an individual animal that is the last of its species or subspecies.” Based on the profile and contribution history of the user who created the entry for endling, he/she was an Australian, so the museum’s influence is there too.

Recently, the word seems to have moved out of Australia. In 2011, Eric Freedman, an associate professor of journalism at Michigan State, wrote an online article about his experiences tracking down endlings, including Martha, the last passenger pigeon. In the article, he brings up the issue of naming, because many endlings like Martha the passenger pigeon and Benjamin the thylacine are given human names:

Perhaps it’s foolish to name individual members of near-gone species. Sentimentality won’t save them. But the naming serves a purpose: It is a way for many of us to identify with the crisis of extinction, just as my pilgrimage to Martha was a way for me to memorialize, and to understand, the demise of the passenger pigeon.

And when Lonesome George, the last Pinta Island giant tortoise and another example of an animal with a human name, died 24 June 2012, an article in the NewStatesmen asked how many more endlings we will see. In this case, the word endling was characterised as “Tolkien-esque” and poignant. An endling represents “the final flickers of something that we are helpless to save.”

Helplessness. Memorializing. Resignation. Regret. Sorrow. These are the things that the word endling names and claims. And that’s why I wonder if it is a useful word. When it gets so bad that there is only one left, there’s little left to do but throw up our arms in surrender. While naming an endling may make us regret, it may not make us act.

4 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback:

Pingback: