Losing control of the Aepyornis

I read a fabulous short story by H.G. Wells titled “Aepyornis Island” which was printed in Pall Mall Budget in December 1894. You can read the story via Classic Reader. It is a story about a de-extinction story told by an old sailor.

In the tale, a sailor who collected island specimens to send back home to English gentlemen collectors had an adventure with de-extinction in Madagascar. He had been collecting eggs and bones of the extinct Aepyornis maximus, a giant flightless bird native to Madagascar, when he became marooned on a nearby small island.

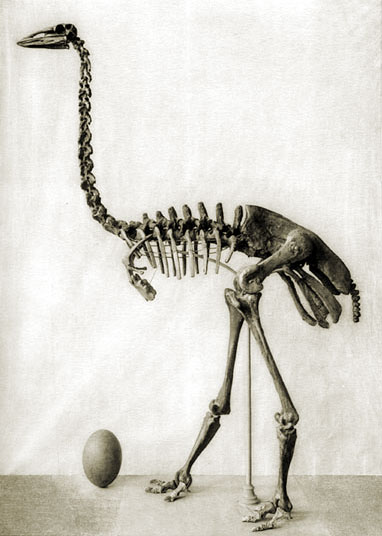

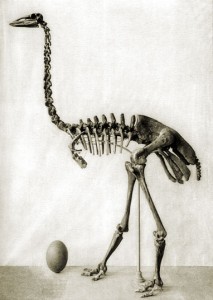

This part of Wells’ story is clearly based on fact. According to Edward Hitchcock, Outline of the Geology of the Globe (1853), the previous existence of Aepyronis maximus had recently been made known through super-sized eggs (equal to 6 ostrich eggs) and bones (the bird would have been 12 feet tall) brought back from the island. Hitchcock was referring to a publication by Isidore Geoffrey Saint-Hilaire from 1851 in which the bird’s discovery was first documented by a zoologist. The public must have also been immediately aware of the discovery. In a literary work dated to 1851, Henry Morley, a professor of English literature at University College London, claims that he would like to be an Aepyornis to lay giant eggs of mischief, noting that “the fossil eggs of that bird now in Paris are sublime.” By the time Wells was writing, the extinction of the Aepyornis maximus and its fossilised eggs were mentioned in popular science pieces such as The Observer: An Illustrated Monthly Magazine of Interchange of Observations for All Students and Lovers of Nature (1893) and Natural Science: A Monthly Review of Scientific Progress (1894). The bird’s mystique had invaded the public’s imagination.

In Wells’ story, when the sailor ends up drifting at sea, he had three Aepyronis eggs with him. He cracked open the first one on the second day at sea and ate it (tasted like duck). On the eighth day, he opened the second one, but it had a developing embryo. He thought it was disgusting, but hey being stuck on a boat in the middle of the ocean makes a man hungry so he ate it all anyway. He still had the third untouched when he came ashore on an island. Needless to say, the egg ended up hatching even though it was hundreds of years old.

The sailor was of course delighted to have some company, so he and the giant bird became friends. In recounting the story within Well’s story, the sailor noted how beautiful the bird was: “After his first moult he began to get handsome, with a crest and a blue wattle, and a lot of green feathers at the behind of him.” The two were always together … until the bird became mature at about 2 years old. Then it started attacking him and the sailor ended up restricted to the tallest palm tree and a lagoon to stay out of harm’s way. Here’s where the story turns:

Think of the shame of it, too! Here was this extinct animal mooning about my island like a sulky duke, and me not allowed to rest the sole of my foot on the place. I used to cry with weariness and vexation. I told him straight that I didn’t mean to be chased about a desert island by any damned anachronisms. I told him to go and peck a navigator of his own age. But he only snapped his beak at me. Great ugly bird, all legs and neck!

Wells stresses in the passage that this bird is “extinct” and this live specimen is an “anachronism.” The bird’s extinction history continues to be in focus with the sailor saying things like “I’ll admit I felt small to see this blessed fossil lording it there” and “It took me some time to learn how unforgiving and cantankerous an extinct bird can be.” The Aepyronis had been de-extincted and the situation was not pretty (interesting to note how when the bird is now an enemy, it becomes ugly rather than beautiful).

As you might guess, the sailor ends up killing the Aepyronis and regrets it, feeling loss and loneliness. He saves the skeleton (like the one in Monnier’s 1913 article) and sells it to a collector after he is rescued. It ends up to be a new larger subspecies than the maximus.

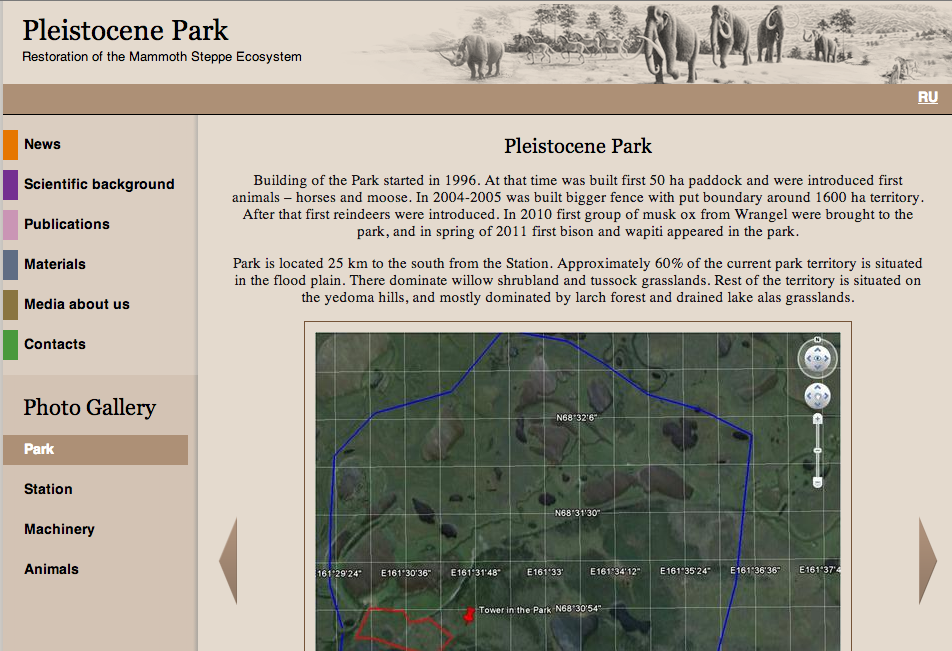

Reading this short story made me think about how humans respond when we lose control of animals. Both de-extinction and reintroduction efforts can be hit by this quandary. The Aepyronis was great to have back as long as it played by human rules, as long as it behaved. But when it didn’t, it had to be killed. This is exactly the same thing that has happened with the muskox of Dovrefjell, which are permitted to roam freely inside of a line drawn on a map, but if they wander outside of that, they are killed. It is also the same with beaver, which are now so plentiful in Sweden that they often create flooding on land humans think should not be flooded. The cover of the May issue of a Swedish hunting magazine features such a story, hailing the marksman who shot the troublesome rodent.

We’re happy with bringing animals back because we’re in control of doing so. But after they are back, we may lose control as they go about doing what they do best, which is to be animals. And sometimes, like the sailor, we may decide to kill what we not so long ago brought back from the dead.