When curiosity kills

On Wednesday, 22 July 1964, 74-year-old Ola Stølen noticed a muskox near his farm in Stølen, a little hamlet in a valley of the Dovre mountains of Norway. He told three other adults about the visitor. They wanted to observe the seldom-seen animal close-up, so they crept up to within 40 meters and stood still, observing the animal for 10 minutes. After a while, the muskox began to snort and then charged the group. Ola was knocked down as the three younger adults quickly ran back to the house. When Ola got up, he grabbed a stone to try to scare away the animal, but the muskox charged again and this time gave Ola a life-ending blow to the chest.

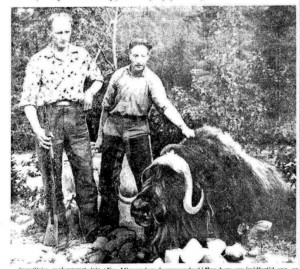

Witnesses called the sheriff, who then contacted the regional muskox manager, John Angard in Dombås, and asked if they could kill the bull. Angard said he would come to take care of it, but before he could get there, the local sheriff and one of those who’d seen Ola killed shot the animal dead.

The local inhabitants were outraged at the death. On 19 August, a telegram signed by 122 people was sent with an ultimatum to the Ministry of Agriculture (Landbruksdepartmentet), which had imported the muskox herd:

The undersigned, all residents of Engan, Oppdal, want to make the Ministry of Agriculture aware that the tragic event Wednesday, 22 July when O. Stølen was killed by a muskox on his property, has created deep unease among folks here. We are therefore bold enough to ask the Ministry to make sure all muskox are removed from the valley between Amotseiven and Driva by Monday 24 August 1964. After this date, all muskox which are found in the said area will be shot. We hope and believe you will understand our reaction.

According to interviews in the papers, the deadline was picked because it was the first day of school. Children were scared to walk the 3-4 kilometers through the forest to school, especially since it would be dark both before and after school by late fall. Women interviewed didn’t want to leave the farm alone for fear of muskox.

Did the Ministry understand the locals’ reaction? It appears that they did take it seriously and investigated what could be done both legally and practically about the muskox. On 28 August, they issued an official response to the Oppdal sheriff saying that muskox were protected legally — the animals could not just be killed — but that a license could be issued to take down a specific muskox which was attacking people. The residents were not satisfied with the answer, but it was the legal answer.

A more important question now may be: Do we understand their reaction?

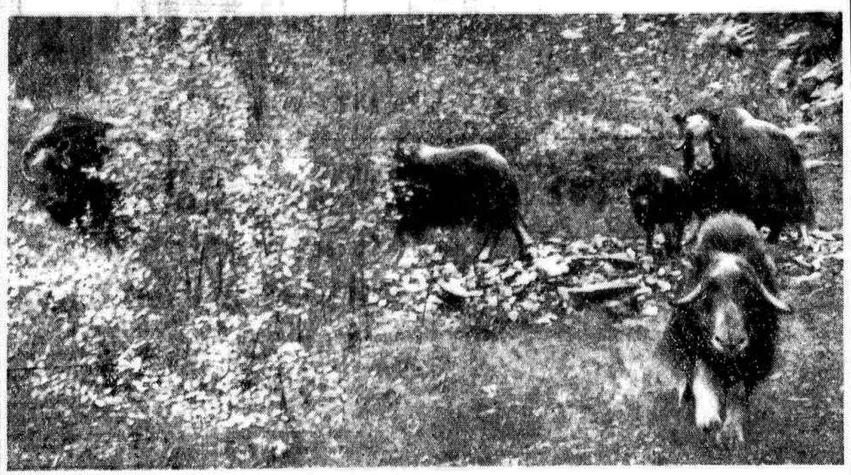

Muskox attacks are not commonplace, but they had been featured several times in the newspapers in the decade before the attack on Stølen. In 1954, a family going into the mountains to pick flowers saw a herd of muskox (with calves) and decided to approach them to take pictures. They got within 30 meters before one charged them. No one was injured, but the action photo of a muskox running toward the camera showed it must have been a pretty scary experience.

In September 1963, a man tried to photograph a lone muskox that had wandered into the village of Soknedal and got thrown up in the air by the muskox’s horns. That animal had been around the village several days and had been roped on one foot and stones had been thrown at it, so I’m sure it was very tired of being bothered.

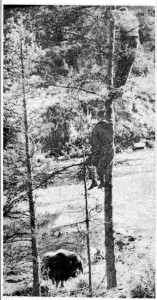

Later that same month, another local man tried to take a photograph of a muskox that had made its way into Tolga, higher up in the mountains. He supposedly got within 15 meters before the animal charged. Although the photographer was knocked down, he was able to recover his camera and take a picture of the muskox standing below two of his comrades up a tree.

What I noticed about all of these incidents was that people had approached the muskox to either photograph it or observe it. They got ridiculously close to them. Today, all of the tourist information says stay 200 meters away which means I need to bring the long lens with me on my field work this summer! Muskox are generally calm animals, but they attack when they feel threatened, which is what getting close to them does. These animals were not attacking people randomly. They were attacking people that they thought were attacking them.

The response by the local community of Engan to Ola Stølan’s death was focused on the muskox. It was the muskox that needed to be removed. The spokesperson for the protest group, Olav Vammervold, was quoted in the paper as saying,

We up here live in a pact with nature, and we obviously don’t have anything against muskox, in the same way that we don’t mind any other animals. But as long as they can’t keep themselves within a particular area, they must be removed.

This pact with nature was clearly not a two-way deal. It was people who set the terms of the contract, and animals needed to obey the human rules.

No one from the local community said anything about the human behaviour that had led to the incident, but one letter to the editor of Aftenposten on 1 September pointed out that the problem was people: “Animals make us better humans. But people, who are animal’s archenemies, can make an animal furiously mad.” People needed to change their behaviour to accomodate animals, which according to the letter author, deserved to be respected.

This kind of conflict is not atypical for reintroductions. People have certain ways of doing things and don’t want to modify those routines, so when a “wild” animals roams onto their property or attacks livestock, they never think it is the human dimension that needs changing — it is always the fault of the animal. At the same time, a reintroduction brings a “new” animal to an area and people can get curious about it, bringing the animal into closer proximity to humans than it would be otherwise. When the animal turns out to behave as, well, wild animals do, again the animal is to blame rather than the human.

The issue at hand is culpability. Who is to blame when people come into conflict with reintroduced animals? I think a muskox had not killed Ola. Ola’s curiosity had killed him.