Hunters as godfathers

I’ll be going to Stockholm in mid-February for a day-long seminar on “Wildlife and Wildlife Management History”. I signed up give a short oral presentation on the role of hunters and hunting associations in my beaver reintroduction story, so I’ve been spending time lately examining that aspect.

I decided to start with some web searches for what environmental historians have written about hunters and hunting associations. I thought I’d find plenty of material. On the contrary, I found a surprising dearth of scholarship. Not that there’s not lots of scholarship on hunting per se and on hunting history — but I wanted something specifically framed as environmental history. I found a couple of articles: Martin Knoll’s work on 18th century European elite hunting and Tom Dunlap’s Sport Hunting and Conservation, 1880-1920. And I read Tina Loo’s book States of Nature, which, while not just about hunters, includes them in the story and has a nice chapter on beaver conservation in Canada. So for those out there searching for a dissertation topic, the environmental history of hunting (and probably fishing for that matter) seems like a wide open field.

Dunlap argued that American hunting at about the same time as my Swedish case was neither about conservation (sustainable management of the populations) nor preservation (completely protecting the animals) but “rather a way to recapture the past and its virtues” (57). Hunting was a ritual activity that demonstrated mastery of nature and manliness. Dunlap admitted that hunters and hunting groups were effective at restricting hunting seasons and techniques in the US during the late 19th and early 20th centuries, but “the desire to hunt supported the impulse to save and to protect” (57). Certainly this was the motivation Loo identifies for the beaver conservation projects in Canada by the Hudson Bay Company, which wanted to increase future prey numbers and thus future profits.

So my question was: Do we see the same thing in Sweden?

The second beaver reintroduction project was taken on by the Västerbottens läns jaktvårdsförening (county wildlife management association; I’ll call them VLJ for short). VLJ was founded in 1919 . The first VLJ director wrote an introductory essay in the group’s first yearbook defining ‘jaktvård.’ He considered it something akin to household management that required care and limits—hunting laws were necessary to protect animals from widespread “jaktlust”. Some people either did not respect the hunting laws or tried to kill as many animals as possible once the hunting season started. The VLJ’s task was thus to arouse interest in hunting “based on love for the animal world and nature”; a love which leads a hunter to “rejoice” when he sees “his wildlife thrive and multiply.” I don’t think this was the same kind of sportsman’s code that came into circulation in North America, which stressed the hunting as a sport and diversion for modern men. In the VLJ texts there does not appear to have been the same distinction between sport and subsistence, nor was there an emphasis on hunting as a modernizing project – a way of getting back to nature – because they didn’t think man had ever left.

It was in the spirit of Swedish ‘jaktvård’ that the association became involved in beaver reintroduction, releasing 7 Norwegian beavers in 1924 in Tärnaån in northern Sweden. Rather than touting human mastery over nature, VLJ advocated stewardship of beavers.

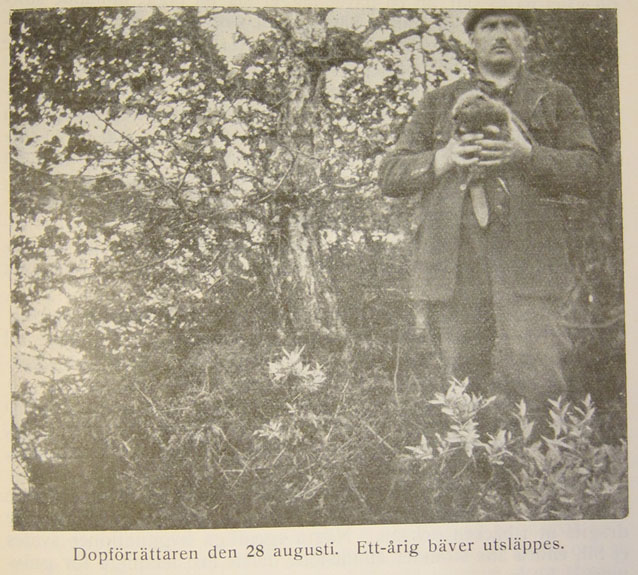

A long article by Lennart Wahlberg about the reintroduction begins by listing the “baptism officiant” (dopförrättaren) and “godparents” (faddrar) for each set of beavers. Wahlberg might have been invoking a double meaning since the beavers were also taking their first dip (dopp) in the new waters. The use of these titles signals that the people present at the reintroduction were more than observers—they became the people responsible for the beaver’s future success. Just as a baptismal sponsor agrees to raise a child to know God and the church, these individuals were agreeing to ensure the beavers’ integration into the landscape. Sponsors are not in a position of domination, but rather facilitation and guidance. When Lennart Wahlberg took a trip in 1930 to check up on the beaver colony, an article written by another member of the group referred to the beavers as the “wards” of Wahlberg, who was listed as the “dopförrättaren” in the release of four beavers on 20 July 1924.

The VLJ was serious about keeping up their sponsorship. The association maintained a “Beaver fund” on their account books to pay for “beaver watch” of the Tärnaån beavers, and a “Beaver report” was included in every yearbook through 1935. The reports noted where beaver tracks had been spotted, trees downed, lodges constructed, and young observed. The reports noted great anxiety when the beavers could not be located or appeared to have abandoned a given area, and great relief when they were seen again.

Interestingly, the possibility of hunting beavers in Sweden post-reintroduction is never mentioned in VLJ articles. Articles often talk about older beaver hunting techniques and beaver products (meat, skins, and medicine), but authors never propose to reinstitute these. If the idea crossed their minds that beaver hunting could in the future be reinstated in Sweden, it was never said aloud.

What was said was that the hunters associations had a duty to right the wrongs of the past. They did not have in mind “preservation” where nature was left to its own or “conservation” with the idea to shoot later beaver progeny. But neither was their motivation the “desire to hunt” as identified by Dunlap. Instead, these hunters felt they had to nurture nature as a godfather, to watch over the beavers and help them succeed in their new homes because previous hunters had failed to take care of them.