Reintroduction as restoration

I recently published an article titled “Ecological restoration in the Convention on Biological Diversity targets” in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation. The article looks at how ecological restoration has been built into the Convention on Biological Diversity (referred to as CBD) targets for 2020. One of the targets establishes a numerical goal of “restoration of at least 15 per cent of degraded ecosystems.” In the article, I discuss the problems of setting up such a quantitative goal when what you mean by “restoration” and “degraded ecosystems” haven’t even been defined.

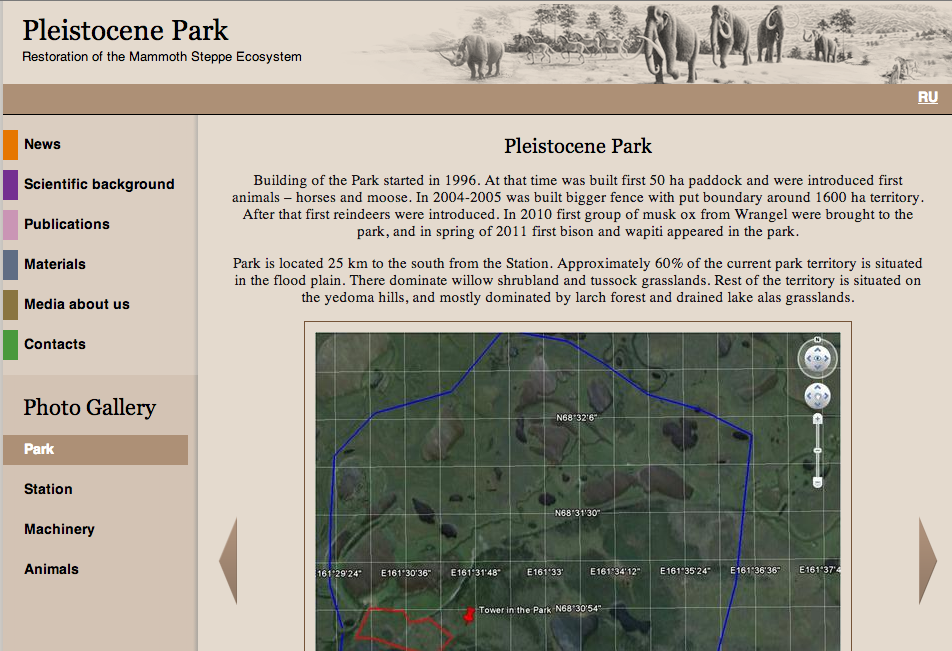

One of the issues I bring up in the article is how reintroduction projects should count, if at all, toward the CBD restoration goal. If a single species reintroduction does count, how would it be measured? By the areal extent of the species’ range? Obviously in terms of biodiversity, which is after all what CBD is supposed to be about, bringing a species back to its former range is positive. But is it a restoration of an ecosystem?

I suppose the answer depends on which species we are talking about and what actions go along with the reintroduction. Some species have a dramatic effect on other species populations which can cause cascading effects through the whole ecosystem. I’m thinking here of the wolf reintroductions in the western US which have been shown to have wide ranging effects. In that case, brining back one species may be the missing piece that can create a more healthy ecosystem.

Sometimes it is also necessary to do restoration of a landscape before a species can be reintroduced. For example, a project to reintroduce large blue butterflies (Maculinea arion) in the UK has required significant investment in meadow re-creation and management in order to promote the colonies of ants (the specific and finicky ant species Myrmica sabuleti) which the butterfly feeds on during the larval stage. In that project, restoring the habitat had to come along with restoring the species.

Lots of other reintroduction projects, however, are aimed at conserving a particular species by reintroducing it into its former habitat with little or no habitat modification. In other words, the projects focus on species, not on ecosystems. It is often unclear in the project summaries I’ve read to really determine the extent to which the reintroduced species “restore” the ecosystem as a whole, even though they clearly modify it by now being in the food chain.

This got me thinking about my historical reintroduction cases. Are they really ecosystem restoration? Beavers are known ecosystem engineers. They physically modify the landscape with canals and tunnels and dams, raising the water level is some areas and lowering it in others. Bringing the beavers back to Sweden in the 1920s and 30s restored an important component of stream and wetland ecosystems.

The Norwegian muskox on the other hand are not drastic ecosystem modifiers. In fact, that’s the reason that modern scientists haven’t called for their extermination even though they are listed on the Norwegian Black List of invasive species — although the scientists consider them non-native, they don’t cause any real harm either. Sure, they eat some mosses and grasses, but the overall effect, at least at the population levels they have now, is minimal. One could argue that the muskox are a component of a tundra ecosystem, so their presence is one step toward tundra restoration (at least if we’re thinking about an ecosystem from 10.000 years ago), but whether or not anything has been significantly restored at this point is pretty questionable.

The relationship then between reintroduction and restoration is one worth continued investigation. They are both “re” words, implying a bringing back, but they may not often bring back the same thing.