A short history of Welsh beavers

The Poly-Olbion Project has begun making available sections of the Poly-Olbion, a long topographical poem describing England and Wales by Michael Drayton published in 1612. One extract is of particular interest for beaver reintroduction. A section of Song 6 talks about the beavers of the River Teifi in Wales.

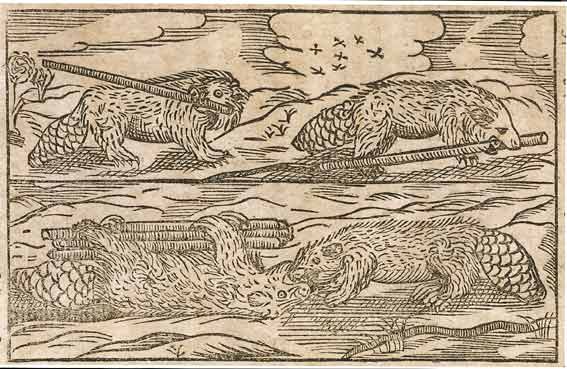

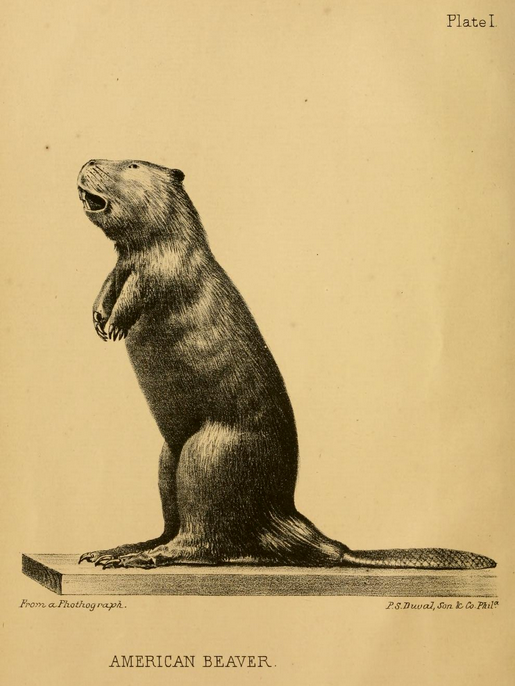

In the poem, Drayton says that the river was famous for beavers “long ago” because “no other brook of Britain nourished” the animal. He goes on to describe the perfect form and shape of the beaver (“this now-perished beast”) with a particular focus on its building habits. Legend, of course, plays a major part in this description, as the beaver is described as loading up one beaver who is laying on his back with sticks and then dragging the beaver and goods home. This trait was commonly discussed in early modern tracts on beavers. Drayton seems to acknowledge that beavers were no longer in the Teifi with his statement that the beaver is a “now-perished beast” which “is to this isle unknown”.

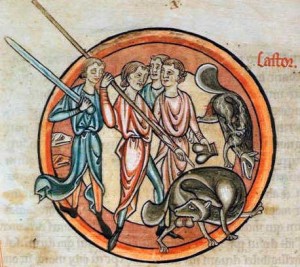

Drayton was taking his information about beavers on the Teifi from Gerald of Wales (Giraldus Cambrensis) who had described them in his Itinerary through Wales from 1191. In Book 2, Chapter 3, Gerald says that beavers in his day were found only in the Teifi and in one river of Scotland. He gives us the longest medieval description of beavers at work, including many details that sound correct and were not common in medieval texts of the time which would indicate that he or someone he talked to had indeed observed beavers in the wild.

Of course, Gerald also repeats many medieval myths about beavers, including that they castrate themselves if pursued by hunters. This myth had a long history. In his Natural History, Book XXXII, Chapter 13 (written 77-79 AD), Pliny says that his predecessor Sextius had previously debunked the myth that “the animal, when at the point of being taken, bites off its testes” since the castoreum sacs which are being sought after are inside of the beaver. Obviously his words of wisdom were not picked up. Claudius Aelian’s De Natura Animalium from two hundred years later repeats the testicle-biting beaver legend as fact. All of the medieval writers would do the same.

We have every reason to believe that there were beavers in Wales at the time of Gerald’s visit, but they must have been extremely rare. The Welsh law codes of Hywel Dda from around the year 945, but existing only in later copies, mention that a skin of a beaver was worth half a pound (= 120 pence), which is much higher than any other animal (stag and ox hides are 12 pence, marten is 24 pence). The law also says that beaver, marten, and stoat skins are reserved for the king because his garments are trimmed with them. Both of these items would appear to indicate great scarcity of beaver, which in turn led to high value on the skin.

Some commentators about the history of beavers in Wales have also mentioned the medieval Welsh Triad (Trioedd Ynys Prydain). They cite the statement in the first book that Wales was “was full of bears, wolves, beavers, and hunch-backed oxen” before people arrived. However, it appears that Iolo Morganwg added beavers to the list in his English translation of 1801 based on Gerald of Wales’ account, so beavers are not in the medieval text.

So that’s a short history of Welsh beavers. And although you might think that is old news, it continues to play a major part in the beaver reintroduction efforts which are ongoing in Wales. The website for the Welsh Beaver Project, for example, includes “facts” about the beaver’s prior habitation of Wales based on these sources. Media coverage commonly refers to the history of beaver: when it was last found and how it died. Articles on BBC News and Wales Online, for example, make the point that beavers died out in Wales because of human hunting rather than “natural causes”. This becomes part of the reason that it should be reintroduced.

I often get the impression that people think historians’ input in ecological conservation like the reintroduction projects I’ve researched is not necessary. They frame the inquiry as a question for “scientists” and by that, they mean biologists and ecologists. But yet if you look at websites and news stories and even scientific articles about reintroduction, you realize that the projects and proposals are soaked in history. The history of the animal, the history of humans, the history of the landscape. These all matter to the history of the Welsh beaver–past, present, and future.

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: