Fundraising

As we enter the Christmas gift-giving season, we are becoming bombarded with requests for money. Advertisements soliciting donations to a plethora of charities from WWF to the Children’s Cancer Fund fill the newspaper pages and the mailboxes.

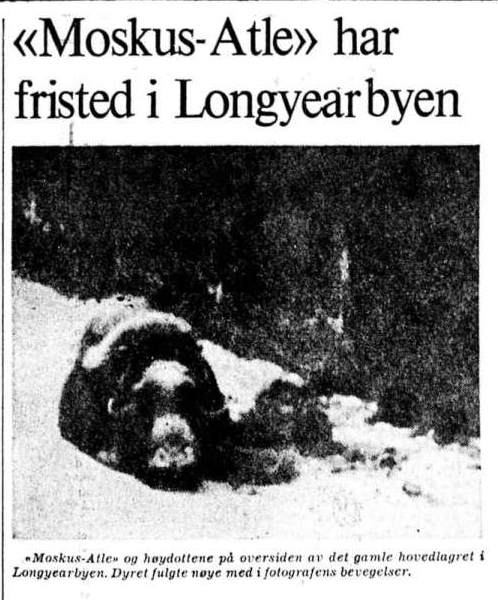

Trying to raise funds for a worthwhile cause is, of course, nothing new. I mentioned before the fundraising undertaken for the Swedish beaver reintroduction projects, which was mainly based on individual private donations, often of very small amounts. Looking through documents about the muskox transfer to Svalbard, I discovered that another strategy was taken by Adolf Hoel and Norges Svalbard- og ishavsundersøkelser (later renamed the Norwegian Polar Institute) to raise funds for their muskox project: corporate solicitation.

When Adolf Hoel decided to import muskoxen to Svalbard, he had to act fast to buy some animals which were already in the country (taken by commercial hunters) before they were sold elsewhere. So he spent money that the Institute really didn’t have on hand. Afterward he needed to fill the economic gap.

He got a 5.000 kr commitment from the Norwegian government for the project, but since the total bill would run to 15.900, he needed to do some more fundraising. He wrote a series of letters in 1929 to some big corporate players in Norway , including Bergenske Dampslibsselskab (Bergen), Nordenfjelske Dampskibsselskab (Trondheim), and Freia Chokolade Fabrik. In these letters, Hoel tried to be saavy and appeal to the particular corporate interests. The letters to the shipping companies highlighted the potential economic value of muskoxen for both meat and wool as raw materials as well as tourism and the support for the project by Fridtjof Nansen and Otto Sverdrup (Hoel is doing some name dropping here). The letter to the chocolate factory stressed the suitability of muskoxen on Svalbard and the nature conservation value of the project, and included five photographs of muskoxen on East Greenland. Both shipping companies replied that they could not support the project financially and Freia replied that their funds for humanitarian causes had already been spent for 1929 thus they could not send anything in support of the project.

Hoel had better luck asking for donations from the hunting and fishing associations, which tended to be heavily involved in wildlife conservation in the interwar period. These included Norsk Jeger- og Fisker-forening (100 kr), Vest-Finmark Jeger- og Fisker-forening (25 kr), Trondhjems Jeger- og Fisker-forening (50 kr), and Østerdalens Jagt og Fiskeriforening (25 kr). It appears that a fund drive among the Norsk Jeger- og Fisker-forening membership produced another 650 kr. But although there were many supporters, this added up to only 850 kr.

Hoel resorted to some individual solicitation. He asked the Crown Prince, who decided to fund the project with 100 kr, on the condition that the size of the gift remain anonymous. He also got an anonymous donation for 3000 kr, as well as personal donations from a Consul General and a dentist totalling 300 kr.

All in all, Hoel did a decent job but came up over 5.000 kr short on his fundraising attempts. When he summarized the situation in February 1930, he noted

I have strained myself to the utmost to get the most possible, but it has been extremely difficult, and the difficulty has been not least that the money was already paid before the collection began.

Obviously the muskoxen had already been released on Svalbard, so the Institute ended up stuck with the bill. I’m not how they covered it but they must have had a hit to the general operating budget. As it seems is still the case, there are more good ideas floating around than people who want to financially support them.

So this Christmas try to remember the muskoxen and beavers and all the other critters out there that need your donations to make conservation projects a reality.

Special thanks to Peder Roberts for scanning these documents for me in the Norwegian State Archives in Tromsø.