A Sami view of muskox

Last week I had the pleasure to participate in The Future of Wild Europe early career researcher conference held in Leeds, England. I gave a keynote address “Conflict in a wilder world: Of muskoxen and men in Scandinavia” on the second day of the event (you can watch my talk here in its entirety).

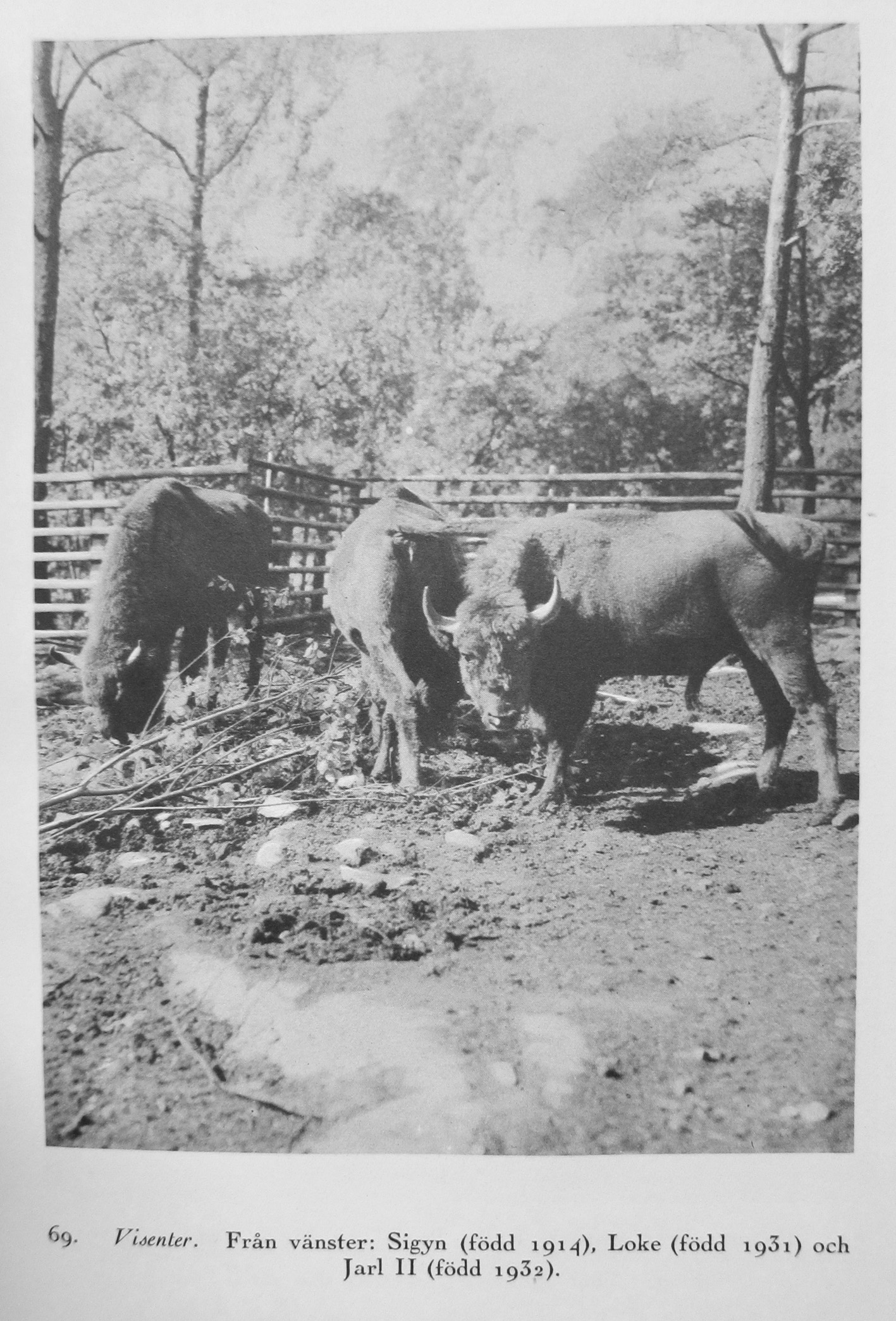

If you’ve kept up with my work on this project, talking about the muskoxen which were reintroduced to the Scandinavian peninsula is nothing new for me. I looked at the muskox relocation from the muskox’s point of view in a 2014 talk I gave at the Rachel Carson Center for Environment & Society (which you can watch online) and the subsequent paper I published with the material (read it in The Historical Animal). Exploring how the story would be told if muskoxen were treated as human migrants, I discussed their forced relocation, unwanted immigrant status, and eventual cultural assimilation.

For The Future of Wild Europe talk, I shifted focus to the human inhabitants of the areas where muskoxen were released. How did they respond to these new neighbours? And how were their view points treated by authorities?

I had discovered in the archives of the Swedish EPA that a symposium was held in September 1976 in the town of Fünasdalen up in the mountains to answer questions about the muskoxen that were seemingly going to stay in Sweden. After a group of five muskoxen showed up on the Swedish side of the Norway-Sweden border in 1971, the local response was mixed. Some people were excited that the muskox might become a tourist attraction. Others were afraid of running into one while hiking in the mountains. By 1976, the five animals had become a herd of 14, so the time was ripe for a discussion about the animals’ future.

The documents related to the symposium and the follow-up muskox policy paper gave me insights about a local viewpoint that I had not been able to include before: the Sami. The Sami, the indigenous people of northern Norway, Sweden, Finland, and Russia, are the only official recognised indigenous minority group in Europe. Reindeer herding is one of their traditional occupations (but not the only thing they are active in) and this would end up in conflict with the muskox population in Sweden.

The Sami reindeer herder Bengt Andersson from Tännäs, who was representing the Sami interests at the September 1976 meeting, wanted guarantees that no more muskox would be allowed in the area and questioned whether or not the ones there now should be allowed to stay. According to Andersson, the Sami objections to muskoxen in the area were numerous:

- There were numerous searches conducted by plane, snow scooter, and foot to locate the muskoxen by both tourists and nature conservation people which disturbed the reindeer

- The muskoxen caused damage to cabins and fenced areas

- The Sami herders who stayed in mountain cabins during the summer to be close to their reindeer could not access their cabins when an animal was in the immediate area

- Muskoxen were feeding in middle of the reindeer flock, making it impossible to gather the reindeer up

- The Sami were worried about the safety of their herding dogs since muskoxen are known (and had on occasion already) attacked dogs.

If the muskoxen were going to be allowed to stay, the Sami wanted compensation for muskox damage according to Andersson.

The response from others in the room was that muskoxen (1) were a “nature protection” object, (2) could bring tourism money to the area, and (3) weren’t any more dangerous that other kinds of wild animals like elks. There were some in the room who agreed that compensation for damage might be appropriate.

In response to the meeting, the Swedish EPA drafted a policy statement (promemoria) on muskox which was sent out as draft for comment to appropriate local, regional, and national authorities as well as scientific experts in 1978.

The response to the draft from the population living close to the muskox was decidedly negative. The Jämtland County government was not happy about the EPA saying that there should be two flocks, which would equate to 80 animals. They wanted a limit of 20-30 animals total. The Agricultural Board of Jämtland also complained about the lack of compensation for damage and security (they had built a new fence for example for a farmer to keep out muskox). Their response letter also mentioned that a dog was attacked and killed by a muskox in one of the Swedish villages. Tännäs Sameby put it simply: “Today muskoxen are always a problem for the Sami village’s reindeer herding and management inside of reindeer grazing areas…there should not be over 20 individuals.”

In spite of these objections, the final version of the policy from May 1979 still listed two complete herds as desirable limit, although the language was softened to a preference. It recommended the muskox be added to Swedish law as a protected species. There were no special compensation packages or any mention of possible damage to farmers and herders. The only thing that was stated was that human death and injury by muskox should be added to law for compensation.

This is a story that shows that even when local input on environmental policy is requested, it is easily shoved aside. The Sami views of what should be done with the muskox did not match the ‘desired’ outcome of the conservation or natural science communities. Thus it was not incorporated into the muskox policy. Just as no one cared whether or not the muskoxen wanted to move to Norway in the first place, no one cared whether or not the Sami wanted them in Sweden.