Native, introduced, reintroduced or missing

A few weeks ago I was giving a guest lecture on databases and how they work for participants in a Digital History PhD course. I called up the IUCN Red List website as an example of a database that is retrieving and displaying information online.

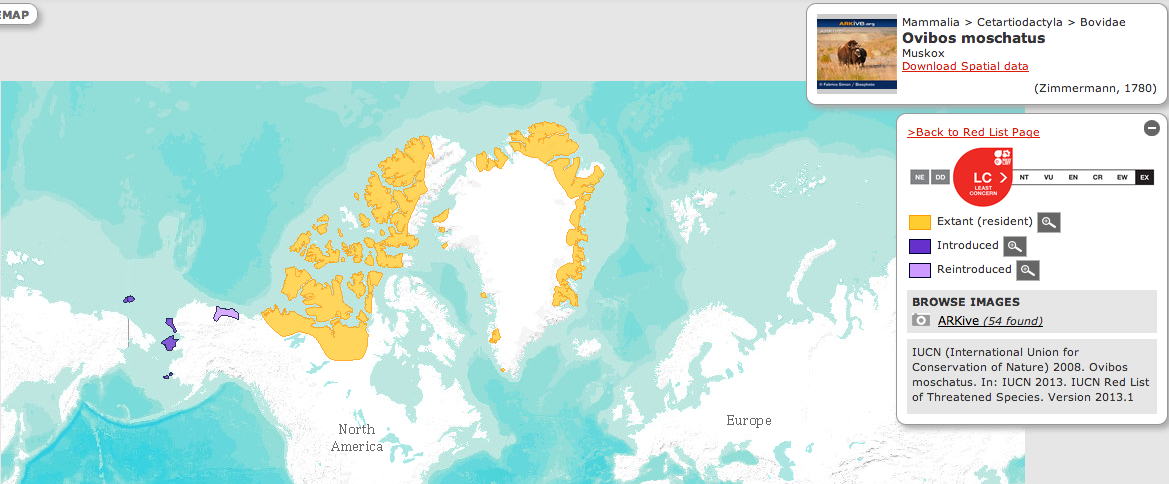

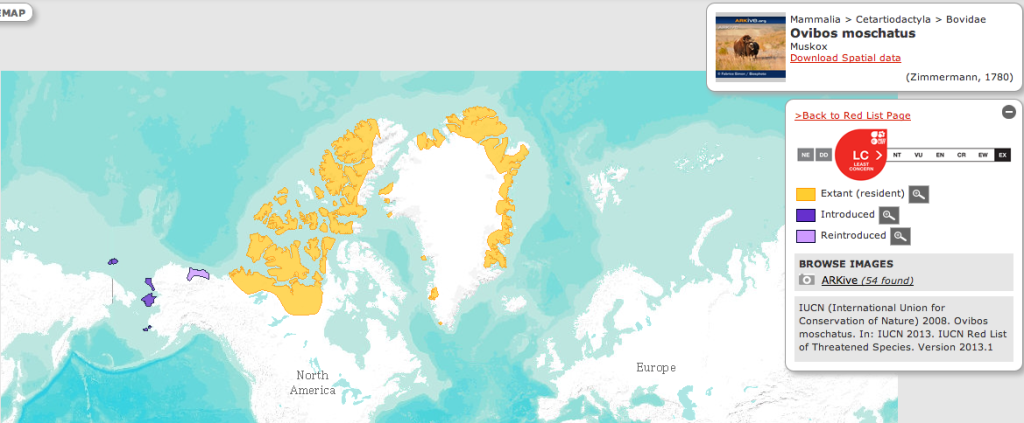

I was showing them around the site using the entry for muskox (Ovibos moschatus) when one of the students looked at the species distribution map on the screen and said, “But wait, there’s no muskox showing in Norway.” “What?!” I replied. Then I looked closer and indeed, there was no indication of muskox living in Scandinavia.

What was going on? I didn’t have time to look into the IUCN Red List entry at the time, but now I’ve come back to it to see if I can make sense of the text and map about muskox.

The first thing I noticed is that the entry attempts to make distinctions about how the muskox population has been established on a country-by-country basis. Under Geographic Range | Countries, it says:

Native: Canada; Greenland

Reintroduced: United States (Alaska)

Introduced: Russian Federation

Now, if you read the text just above that information as well as the “Population” section below it, you will see that these assessments based on nation-state boundaries don’t conform with the scientific assessments about the distribution. For Greenland, for example, the authors say:

Muskoxen occur naturally over the entire Northeast and North Greenland west to Nyeboe Land. As well, there are several introduced populations, which are now well established in West Greenland and Qaannaaq.

This means that classifying Greenland as “native” isn’t quite right because the authors have classified some populations in Greenland are “natural” and others “introduced”. The same problem holds true for Canada where the text notes that muskox are found in Yukon and northern Quebec “outside their natural range”. The framing of conservation at a nation-state level is so strong that the classifications are made at the country level even though a simple classification is contradicted by the information presented adjacent to the list. It’s interesting to note in the map that none of these caveats are taken into account. Canada and Greenland are given only yellow “native” populations. on the map.

Secondly, there is the entire problem of what constitutes “native”, “reintroduced” and “introduced”. At the time this entry was written (in 2008), the IUCN Reintroduction Guidelines defined “reintroduction” as “an attempt to establish a species in an area which was once part of its historical range, but from which it has been extirpated or become extinct.” I’ve written an article about confusion with the “historical range” formulation (which has since been modified in the 2012 IUCN Reintroduction Guidelines), but in any case, that was the definition at the time. So if the species had previously been in a place, it should have been listed as a reintroduction; if species was taken to an area outside of its “historical range”, it should be labelled as an introduction.

The authors appear seriously confused about the status of the muskox. For example, they wrote:

As well, there are several introduced populations, which are now well established in West Greenland and Qaannaaq. The species was re-introduced to Alaska (USA), and four locations in West Greenland (Denmark).

Now maybe I’m crazy, but I think the first sentence says muskox were introduced to West Greenland and the second says they were reintroduced to West Greenland. So which is it?

For Russia, there is also confusion. The text says: “The species occurred in Russia until around 2,000 years ago, and has been introduced to the Taimyr Peninsula and Wrangel Island.” Here, the authors have not counted the species occurrence in the distant past as part of its “historical range” and thus have labelled muskox as “introduced” there. On the map, there is one dark purple “introduced” area on Wrangel Island, but there is no population shown on the Taimyr Peninsula at all. Considering that the Taimyr population is around 6500 individuals and was established in the mid-1970s (Sipko 2009) and there are several other muskox populations in Russia as well, the oversight seems inexcusable.

Finally, and really most relevant to this project, where are the muskox in Scandinavia? The map shows no range at all for muskox in Scandinavia, but if you’ve read anything on this blog, you know that there are muskox roaming free around in Norway and Sweden. The authors have one sentence in the text about Scandinavian muskox: “Muskoxen were also introduced to Norway and Svalbard (Norway), although on Svalbard, they have since died out.” Based on this sentence, we would expect that there would be a dark purple spot in Norway, but there’s not. Of course, I could object to the sentence as written anyway. Muskox were present in the Scandinavian peninsula a few thousand years ago, so their presence is within their “historical range”, thus the map should have a yellow blob in the Dovre mountains area. And on top of that, there is the group of muskox that have established their range in the Rogens-Femundsmarka borderlands so the blob should extend into Sweden and the Swedish population should be mentioned in the range description. As it stands, the Scandinavian muskox are missing.

I’m left feeling very disappointed in this IUCN Red List entry. The two authors are muskox experts – I looked up their long list publications and they are certainly qualified to talk about muskox – but obviously they have not looked very far outside of the home ranges of the muskox populations they personally study in Canada and Greenland. Information is certainly available on the reintroductions in Norway, Sweden, Russia, so it shouldn’t have been hard to find it. I also wonder about the mapmaking process for the List, since obviously the mapped ranges don’t match the entry text. Where did the map come from? How did the map creator miss populations discussed in the text?

A detailed analysis of an IUCN entry like this can open up for all to see the built-in definitions, national frameworks, and biases with which scientific texts get produced. Decisions have been made that have rendered muskox around the world native, introduced, reintroduced, or missing.