War on wildlife

When I was in London at the end of October, I saw a barrage of red poppies. They were everywhere — on signs and stores and lapels. As an American, I will admit being confused about what they were for when my daughter asked me, so we talked to a guy on the bus wearing one. I found out that they were for Remembrance Day or Armistice Day — November 11 — which marks the end of World War I and honors those who fell in the ‘war to end all wars’. The poppies will likely be a common sight over the next few years since 2014 marks the 100th anniversary of the start of the conflict.

Historians will also be doing work to re-examine WWI as well as other conflicts and their legacies in memory of the centennial. Part of the recent re-evaluation of war includes its environmental history, with recent scholarship such as Natural Enemy, Natural Ally (2004), War and Environment: Military Destruction in the Modern Age (2009), and Arming Mother Nature (2013). There has also been interest in recovering the stories of animals in war such as in the collection Animals and War (2012). There is even an Animals in War Memorial in London unveiled in 2004.

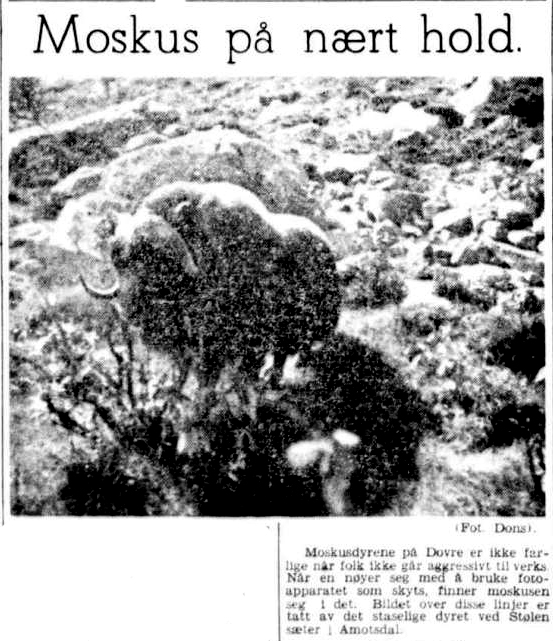

Like many other animals, the muskox in Norway is wrapped up in a wartime narrative. Norway was invaded by the Germans in 1940, who wanted both ice-free northern ports and the mineral wealth available in the country. During the German occupation, the muskox herd in the Dovre mountains disappeared. What happened to them?

The whole story is not entirely clear, but a particular shooting of a Dovre muskox by German soldiers on 22 September 1944 produced a Rashomon-like assemblage of stories about a muskox murder. From the viewpoints of informants I found documented in the Norwegian National Archive, here’s what happened:

Der Reichskommissar für die Besetzten Norwegischen Gebiete official report, dated 27 Sept 1944

Officer Haseman had seen a muskox mingling with a herd of grazing cattle. The soldiers were on patrol looking for escaped Russians [from the prisoner of war camps]. Finally the muskox saw them and ran toward lieutenant Hennig, which is why soldier Burchardt shot it. The lieutenant himself fired the second shot, then the game animal crashed into the ground. Burchardt fired the kill shot.

Skogdirektøren (Forest administration) report

After the muskox had been seen, two Germans with rifles went to hunt it. A man from the highway administration went after them, made contact with the hunters, and told them that the animals had complete protection and that killing was forbidden. In spite of this, the Germans continued the pursuit and shot it.

O. Olstead (the veterinarian in charge of muskox), likely based on account from John Angaard from Dombås, dated 9 Oct 1944

A muskox was seen near Hjerkinn station by several people. After a while, it headed out of the area. Later witnesses saw 2 women and 3 uniformed officers, two of which had rifles, headed toward Snøhetta. Because he was afraid that the hunters were intending to shoot the muskox, a man ran after them to tell them that the animals were protected. When he got to the area, the hunting party had split into 2 groups, but luckily he was able to tell both groups about the situation. After the messenger had gone a distance toward home, he nevertheless heard 1 or 2 shots in the direction of the muskox. He then saw the hunters with women gather together where the animal was felled.

Reidun Michelsen, 16 years old, eyewitness report taken 30 Jan 1945

On that day Reidun Grønbekk, three German soldiers (a lieutenant, a junior officer, and a regular soldier), and I went on a walking tour. When we came over a hill we met Titus Åboen who told us that there was a muskox in the area and he pointed in the direction to where it was. We crept over so that we were at a distance of 20-25 meters, and we laid there and watched for a while. We went back to the hill and sat down to eat when the ox came running toward so. When the ox was 15-20 meters away, the junior officer shot it in self defence.

Reidun Grønbekk,16 years old, eyewitness report taken 7 Feb 1945

At midday, we [Reidun and his friend Reidun Michelsen] saw a muskox walk by the Hjerkinn train station. We went over to see it closer. Three Germans–a lieutenant, a junior officer, and a regular soldier–came by on a motorcycle. My friend Reidun knew the junior officer. When we got 40-50 meters from the muskox I stopped because I was afraid to go closer. The others crept forward until they were 10-12 meters from it. The muskox eventually got mad and ran toward us. The junior officer shot at the muskox and it fell. It got right up again and the junior officer shot one or two times more sot that it was dead.

____________

So there you have it. Many versions of the same event.

After this incident, there were investigations into the status of the Dovre muskox herd. The Riksjegermester (national hunting administrator) Solbraa asked for local reports about the numbers and whereabouts of the animals. The reply from the Opland wildlife and hunting coordinator indicated that 16 animals had been seen in spring 1944, and since 4-5 calves would be expected, there should be about 20 of them. This was the same message received from the coordinator in Dombås.

But the report from the Klæbu district hunting coordinator painted a more dire picture: no one he talked to had seen any muskox that year and on top of that a number of them had been illegally shot. According to him, only one animal had been seen in Opdal in 1942 and 43 and only three had been seen in Åmotsdal. He was unsure if the muskoxen had all died or simply relocated.

Adolf Hoel (the man who was head of the Polar Institute that had brought the muskox calves to Dovre) sent a letter on behalf of the nature protection association Lansforbundet for Naturfredning i Norge to Solbraa asking him about the status of the herd. Hoel had heard that the herd had been greatly reduced by illegal felling. Solbraa’s reply on 15 February 1945 was that the status was unknown, as apparently the muskoxen had split into small herds or lone individuals. He did, however, confirm that two muskoxen had been shot by Germans.

After the occupation was over, the Germans got the blame for the muskox’s disappearance. A headline in Aftenposten on 21 November 1945 claimed ‘Germans exterminated muskoxen’, although text of the article states: ‘in winter 1943-44 German and “Norwegian” hunters lived in two cabins in the district where the muskoxen stayed. The animals were tame and easy to shoot, and it is possible that it was that winter that the most animals were killed.’ (note that the report put the Norwegians in quote marks). Another article from 7 March 1946 likewise sported the headline ‘No muskoxen left in Norway. The Germans took them’. The evidence in support of the claim was two fold: (1) the 1944 shooting by ‘”Germanic’ hunting companions’ (again Germanic is in quote marks) and (2) a German officer in Trondheim had a mounted muskox head delivered to him, which although the officer claimed it was from Svalbard, must have been from Dovre.

The story was thus built up that the Germans shot and killed all the muskox of the Dovre mountains. Maybe they did. Maybe they didn’t. After all, there were terrible food shortages in Norway during the occupation, so one muskox would have fed many mouths. We may never know. Such is the cost of war.