The fauna of post-glacial Sweden

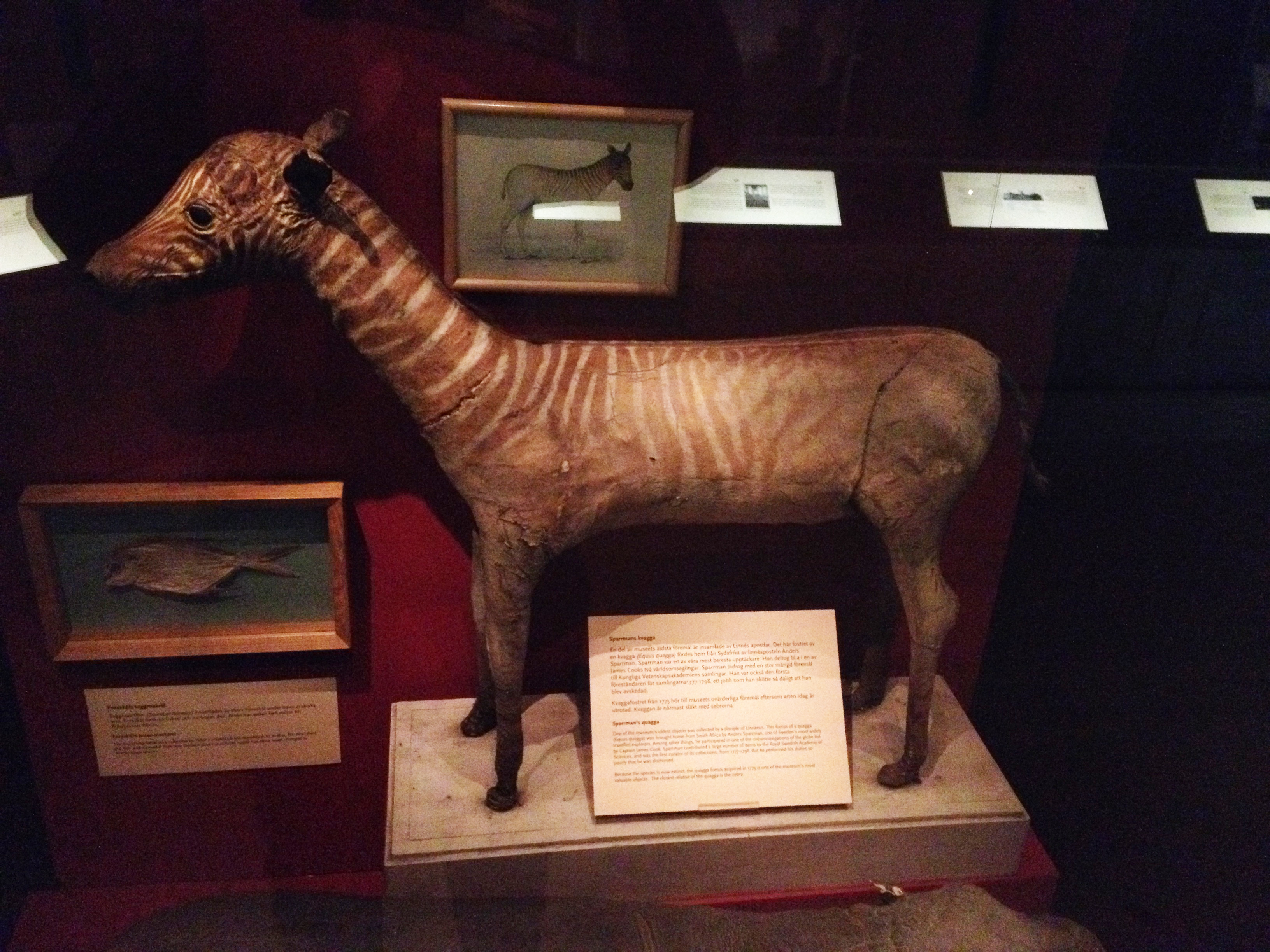

The Lund University Historical Museum has recently opened a new exhibit ‘Sven Nilsson and Skånes post-glacial fauna’. The natural history exhibit displays a mix of taxidermy and skeletal specimens of the animals which moved into southern Sweden when the glaciers retreated after the last ice age about 10,000 years ago. It is based on the work of Sven Nilsson (1787-1883), a leading Swedish zoologist who published an impressive multi-volume on Scandinavian fauna (first volume in 1820), headed the Natural History Museum in 1828-1832, and then became a professor of zoology at Lund University.

Nilsson looked for both past and present evidence of animal colonisation, arguing that some animals, including bears, beavers, wild boar, and roe deer had entered Scandinavia from the south, whereas other animals, including the arctic fox, lemmings, and hares, had come down from the north. Some of the animals he identified as being in Scandinavia in the post-glacial period existed only as fossils. In a follow-up volume of Scandinavian mammals published in 1865, August Emil Holmgren noted that of the animals identified by Nilsson,

many already extinct here, such as wild boar, aurochs, and more, or on their way to extinction, such as red deer and beaver.

The exhibit features both kinds of animals–those known only from fossils and those which had still inhabited Scandinavia when Nilsson wrote. Texts with natural history information about individual species is presented both next to the specimens and on touch screens that visitors can use to select the information about whichever animal they wanted. The displays ingeniously use iPads for all the text and images–which has three advantages I can think of: (1) the iPad displays ‘scroll’ through different texts and images, making paper labels unnecessary, (2) the devices could potentially be updated with new information, which would also save on relabelling, and (3) the devices can be relocated in the future to other exhibits if needed and the text easily updated.

I’ve mentioned missed opportunities to tell extinction stories in natural history museums before. In this case, some of the animals’ texts actually did tell those stories. With the moose (Alces alces), the visitor reads that:

Although moose in Scandinavia were almost totally extinct in the middle of the 1800s, the present Swedish population is Europe’s densest.

With the wolf (Canis lupus), we learn that:

The native Swedish wolf population died out in the middle of the 1900s. Single individual have been able to immigrate from the east and today’s approximately 300 Swedish wolves are derived from these.

This wolf text is very interesting in the way that nationality and belonging is ascribed. In it, the wolves that lived in Sweden up to the mid-1900s were ‘Swedish’ but so are the wolves that have recolonised Sweden. There is a distinction between wolves that were ‘native’ and wolves that ‘immigrate from the east’, but they are both still ‘Swedish’. In other words, I would say that they are considered to belong.

The text accompanying the beaver (Castor fiber) includes a quote from Sven Nilsson dated 1847:

Long ago, perhaps before the true historical period, the beaver ceased to exist here in Skåne. … One can see the beaver skeletons which are not infrequently found in peat bogs, which used to be watercourses and lakes.

The beaver by Nilsson’s time was already very, very rare in all of Sweden, but it was and still is very rare in Skåne. In fact, none of the reintroductions by 1940 took beavers as far south as Skåne. The closest was Järnäs in Småland about 130 km west of Stockholm. Beaver is still rare in Skåne (the beaver specialist Göran Hartman does not show it inhabiting Skåne in his distribution map from 1999), but some must be moving into the area from reintroduced populations further north, evidenced by a news article from September in which people were worried about a beaver being ‘trapped’ on a river island in Norrköping. Unfortunately, other than Nilsson’s quote about Skåne, the larger extinction and reintroduction story of the beaver was not told in the exhibit.

Overall the message of the exhibit was that there were once many more animals that inhabited southern Sweden than do so now. And that kind of message is important for visitors to hear.

One Comment

Erika Rosengren

Thank you so much for this wonderful review!