The Fruitful Arctic

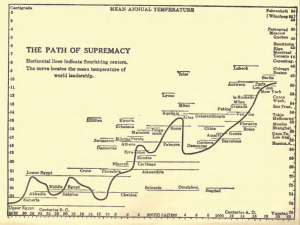

In 1922, the Arctic explorer and ethnographer Vilhjalmur Stefansson published his book The Northward Course of Empire in which he argued that the North had been greatly misunderstood and could become a seat of great civilisation. After all, he argued, civilization had been moving further and further north into the colder regions over human history.

The North, rather than being a barren wasteland devoid of vegetation, was a green space. The trick, Stefansson argued, was to turn the vegetation to productive use:

The realization kept gradually growing on me that one of the chief problems of the world, and particularly one of the chief problems of Canada and Siberia, is to begin to make use of all the vast quantities of grass that go to waste in the North every year. The obvious thing is to find some domestic animal that will eat the grass. Then when the animal is big and fat it should be butchered and shipped where the food is needed. (48)

Stefansson believed cattle and sheep were not the answer to this problem because of the problem of feeding and sheltering them during the winter. Traditional crop plants could also not withstand the frosts. Instead he decided that the solution to this waste was the widespread domestication of reindeer and muskox in the North.

Stefansson began actively promoting the animals after World War I. With his encouragement, the Canadian Department of the Interior set up a royal commission in 1919 to study the possibilities and they issued their final report in 1922. The report comes out more in favour of reindeer than muskox because of prior work domesticating reindeer, but it also encouraged further investigation of industrial possibilities for muskox domestication.

Stefansson may have first become acquainted with muskoxen (which he called ovibos based on the Latin name because he disliked the ‘musk’ and ‘ox’ connotations of the regular name) during his time in the Mackenzie Delta of Canada in 1906-1907. The presence of a hand-colored lantern slide of a muskox herd dated 1906 in his collection at Dartmouth College makes this likely. Stefansson had eaten plenty of muskox on his various Arctic expeditions and offered the opinion that “not one person in ten could even when on his guard tell an ovibos steak from a beefsteak” (The Friendly Arctic, 585). He also noted that muskox wool (qiviut) was high quality, although it was difficult to collect and spin because it was mixed with longer hairs. In his descriptions of muskox in The Freindly Arctic (1921) and The Northward Course of Empire (1922), he claimed that the animals do not roam in search of pasture, seldom attack, and seldom flee. All in all, the muskox was the perfect animal to make the North productive:

When we sum up the qualities of ovibos, we see that here is an animal unbelievably suited to the requirements of domestication–unbelievably because we are so habituated to thinking of cow and the sheep as the ideal domestic animals that the possibility of a better one strikes us as an absurdity. We have milk richer than that of cows and similar in flavor, and more abundant than that of certain milk animas that are now used, such as sheep and reindeer; wool probably equal in quality and perhaps greater in quantity than that of domestic sheep; two or three times as much meat to the animal as with sheep, and the flavor and other qualities those of beef. When you add to this that the animal does not roam in search of pasture, that the bulls are less dangerous than the bulls of domestic cattle because they are not inclined to charge, and that they defend themselves so successfully again packs of wolves that the wolves understand the situation and do not even try to attack, it appears that they combine practically every virtue of the cow and the sheep and excel them at several points. (The Friendly Arctic, 587)

With a pitch like that, it’s a wonder everyone didn’t run out and buy a muskox! Although Stefansson may sound like he is overselling his product, others would adopt very similar language in touting the muskox as Svalbard’s future meat supply in the late 1920 and the next knitting industry of northern Norway in the 1960s. Even in 1946, Stefansson was still promoting muskox as a domestic animal, this time saying that it was “the most promising animal for New England” in an article in Harper’s Magazine. Stefansson’s vision was directly transmitted to John Teal Jr., who started an experimental farm in Vermont in 1954 to raise muskoxen and later moved his operation to Alaska.

The vision of turning the ‘unused’ land of the North into a fruitful Arctic was powerful. It encouraged both domestication and reintroduction projects of muskoxen in Norway, Alaska, and Canada over the course of the 20th century. The land of snow and ice would be a land of meat and wool.

2 Comments

Pingback:

Pingback: