First year reflections

The end of 2013 also marks the end of the first year of “The Return of Native Nordic Fauna” project. It’s been a year that has really gotten the project off to a running start. I’ve documented the course of the project on this blog since it’s beginning on January 1, but as some readers may not have been following along all that time, I wanted to take the opportunity to reflect on the year.

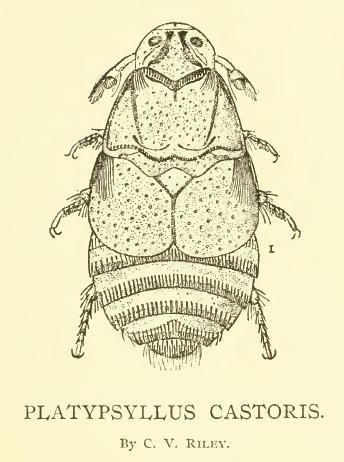

During the year, I’ve skipped around Norway and Sweden working in archives, trying to decide what to copy and what to leave behind from the Skansen archives held by the Nordiska Museum in Stockholm, the Jamtli archives in Östersund, the National Archives and National Library in Oslo, the Norwegian Polar Institute in Tromsø, and my home university library in Umeå. I’ve also spent countless hours finding digitized newspaper articles and journal articles from the late 1800s and early 1900s, a process which also illuminated gaps in the record. During those days leafing through dusty, often hard-to-read handwritten papers, I discovered that people tried to donate some odd animals to Skansen, that muskoxen disappeared during the German occupation of Norway and soldiers got the blame, and that Peder M. Jensen Tveit (aka the beaver whisperer) sold rare beaver beetles in addition to the beavers themselves.

Luckily this project has also permitted me to move beyond the historical archive into other sites. I’ve gotten to spend some days outside doing field work where I found out that beavers have been incorrectly identified as lizards on rock carvings, I observed a wild muskox herd through a steady rain in the Dovre mountains as well as captive muskoxen at the breeding center in Tännas, and photographed wild beavers swimming past my boat. The research year has been a barrage of real sensory experiences that has included eating muskox meat, drinking castoreum liquor, and feeling soft and warm muskox wool.

Some of my favourite research stops have been at museums and zoos, where I have examined the ways in which the stories of reintroduced beavers and muskoxen in museum settings are presented to the public. I’ve thought about how exhibits often erase individual animal’s stories to tell species ones, but there are certainly exceptions, like Bruno the Bear in Munich. I’ve visited zoos in Östersund and Lycksele, seen stuffed beavers in an Estonian forestry museum, and examined the contents of an apothecary shop from Robertfors that sold castoreum as medicine.

Although my research has focused on the reintroduction of beavers and muskoxen, I’ve also thought about other reintroductions such as the debate about wild boar in Britain, wisent in Germany, speeding up the spreading of cranes, and woodpecker releases. I’ve mused on fiction literature that deals with reintroduction, including Star Trek, H.G. Wells, and Dr. Seuss. I’ve even gotten to bring in my medieval history interests with posts on St. Francis and the wolf and Olaus Magnus’ map.

I’ve had the chance to share some of my early findings at conferences and workshops in 2013. In February, I talked about hunters as godfathers of beavers at a wildlife history workshop. In March, I argued that Skansen and its director Alarik Behm were an obligatory passage point in the beaver reintroduction at the Swedish History of Technology and Science Days. In August, I talked about the deployment of the muskox’s historical presence in Scandinavia as a reintroduction justification at the European Society for Environmental History biannual conference. In November, I presented the boxes that carry translocated animals as transformative at the workshop Animal Enclosures in Oslo and Northern Nations, Northern Natures in Stockholm. In December, I conceptualised muskoxen as migrants at the Rachel Carson Center lunchtime colloquium in Munich.

One of the most exciting things about this project has been the sidetracks — or should call them productive diversions? — that I’ve been led down. I discovered the word endling and its fascinating history, as well as entered the debate on de-extinction with an article in Bioscience linking de-extinction and reintroduction. I presented a history of the idea of rewilding at a workshop in Cambridge, was interviewed in a podcast as a follow-up, and am currently preparing a revised version of the manuscript for publication.

All the while, I’ve been thinking about how historians tell stories, how story-telling makes cultural memories, how artefacts like maps and stuffed animals might affect our perceptions of belonging, how definitions of nativeness matter, and why we need history-telling to help us remember and make better policies. I’ve also reflected on the challenges of interdisciplinarity and the truths of academic publishing. These broad reflections can have lasting affects on the way I write history and hopefully the way others write and read history in the future — my case studies of beavers and muskox are really the means to an end.

I’m looking forward to Year 2 as I continue to deepen and broaden my research. I hope you’ll take a moment to explore the Year 1 posts on this blog then follow along in 2014 as I share more discoveries.