The hidden reintroduction

I recently discovered the letterhead of P.M. Jensen Tveit of Aamli, Norway, in the archives of the Natural History Museum, London. It appears that Jensen Tveit contacted the museum in the 1920s to sell beaver specimens to them. He had also contacted Skansen’s zoological division about the same time. But what Jensen Tveit was selling according to the letterhead is fascinating:

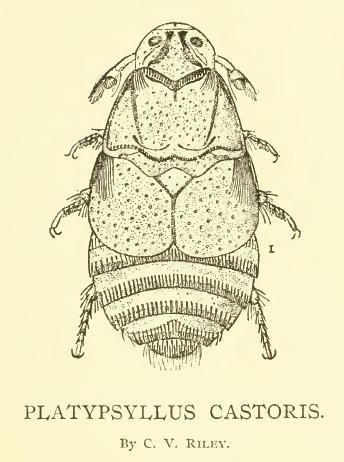

Living beaver (Castor fiber) for release and for zoological gardens, stuffed beavers, craniums, beaver beetles (Platypsyllus castoris), as well as skeletons and spirits for use as teaching materials

What caught my eye was beaver beetles. I expected all kinds of beavers living and dead, but beaver beetles? What were those? And why would he be selling them?

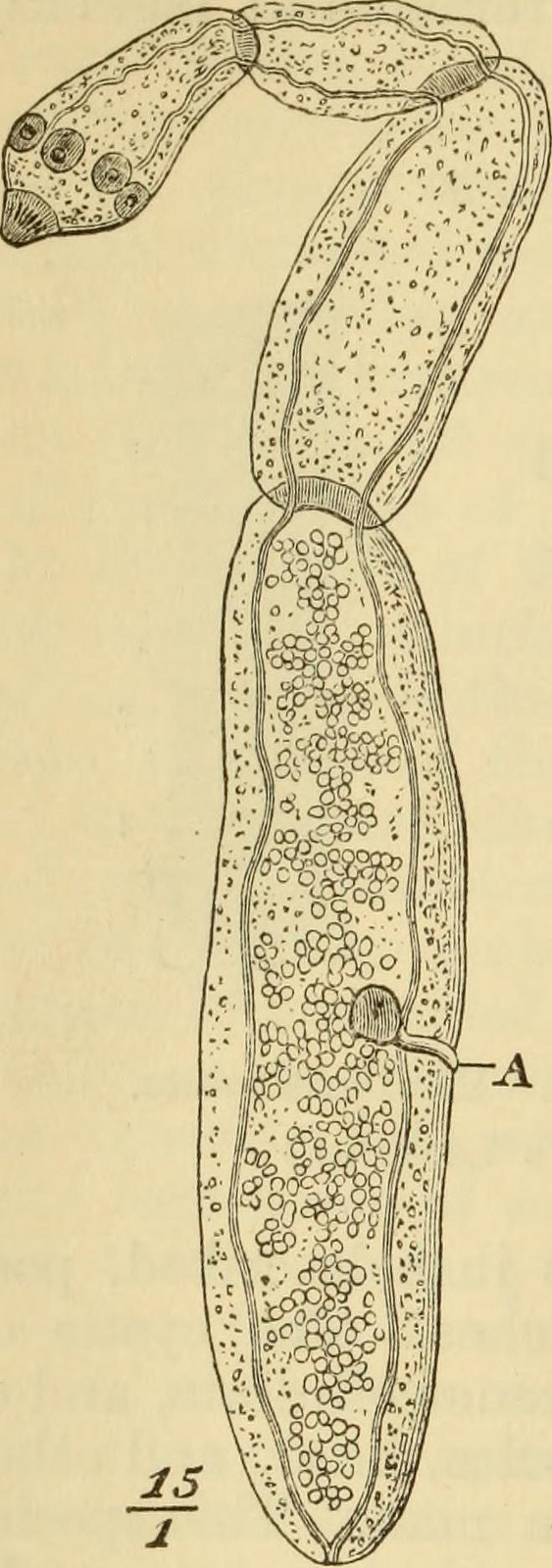

It turns out that Platypsyllus castoris is a super-specialised beetle that lives on beavers. It is a blind beetle 3-5 cm in length that lives both its larval and adult stages on the fur of beavers. It does not have the ability to pierce the skin so it eats only secretions from the skin. It leaves the beaver’s body to pupate, but it remains within the beaver den.

It was first described by an entomologist in 1869 after it was found on a Castor canadensis in the Amsterdam zoo. In 1884 it was described in the wild European beaver remnant in France and in 1886 in wild beavers in North America. Because of this history, there has been some question as to whether the beetle was indigenous on both sides of the Atlantic, but it appears to be (see Peck 2006).

In Peck’s article, he asks why the beetle was described so late in the entomology game, but he doesn’t provide an answer. I think the answer is the rarity of beavers in Europe and the limited access to live ones in Canada. That the beetle was first found in a zoo specimen seems to me entirely reasonable considering the historical moment in time in the late 1800s with almost no beavers left in the wild.

So why was Jensen Tveit peddling these beetles? It turns out that the beetle’s odd behaviour of using the beaver as host in both the larval and adult stages, as well as a debate about whether it should be in the beetle family or the flea family (there was even a letter published in Nature in 1872 about which family it belonged to), was really interesting to entomologists. Who better to provide museums and scientists with specimens of a coveted and rare beaver beetle than a man who had ready access to beavers!

There have been a slew of recent scientific articles noting the “first recording” of the beetle in a specific European country — Latvia in 1995, Belgium in 2000, Slovakia in 2001, to name a few I found. In reality, this is not the first time the beetle has been in those places. As beavers have been reintroduced across Europe, Platypsyllus castoris has gone with them. Animals are ecosystems too; the beaver is the beaver beetle’s one and only home. So it’s only natural that the beaver beetle is now showing up in places that have regained beavers. It has been a reintroduction hidden in beaver fur.

One Comment

Pingback: