Two expeditions, six calves, and one forgotten story

Being a historian is part reader, part writer, and part detective. It’s about uncovering stories that have been lost to time, whether forgotten, ignored, or intentionally covered up. This week, I discovered a small part of the muskox story in Sweden that few seem to remember today. While the history of the failed attempts at raising muskox in Norway is often mentioned – the failures both on Svalbard and in Troms – I’d never heard about Sweden doing such things. But it turns out that Sweden actually had muskox in the country before Norway in the modern era. After reading a short statement that sparked my interest, I spent some time tracking down the story of the first live muskox brought back to Sweden. Here’s what I found out.

In 1899, the Swedish geologist Alfred Gabriel Nathorst led an expedition to Greenland. According to his book recording his adventures, Nathorst observed wild muskox herds during the expedition and came to the conclusion that the Swedes should try to import and domesticate the animals. The main purpose of such an endeavour would be to corner the market on muskox wool, which as I noted before is considered one of the highest quality wools available. He believed that the muskox would acclimatise perfectly to Sweden and be even more productive than reindeer, since it was more tolerant of mosquitos, less prone to wolf predation, and did not require long-distance migrations over the year to new feeding grounds.

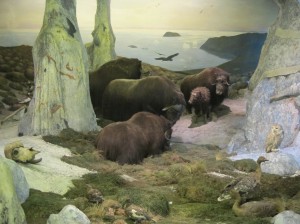

The following year, in 1900, the zoologist Gustaf Kolthoff led a Swedish expedition to northeast Greenland sponsored by G.E. Broms. The tasks included bringing back specimens for the museums including the Biological Museum in Stockholm and capturing living muskox, as suggested by Nathorst who had championed the cause of bringing back muskox for domestication.

Capturing live muskox calves was no easy task. Kolthoff described the difficulties in his memoirs for the expedition, Til Spetsbergen och Nordöstra Grönlandår 1900. The expedition members decided that since the calves were well-protected by the herd adults, the only way to capture the calves was to kill the adults in the herd first. Kolthoff offered a justification for the decision:

Surely two muskox calves in Sweden are much more valuable than six in Greenland.

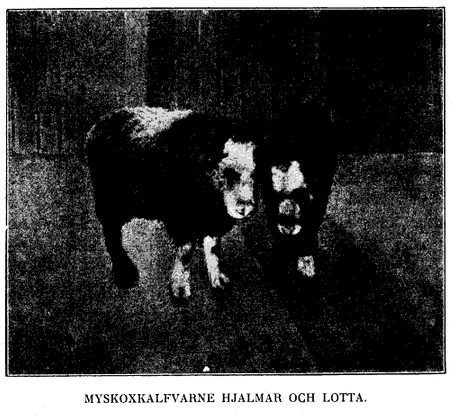

After several failed attempts, the expedition was finally successful at capturing a male calf, which was named Hjalmar in honor of expedition member Hjalmar Östergren. After another week, they successfully captured a female calf, named Lotta after Kolthoff’s wife Charlotte. Unfortunately, bad weather cut the expedition short so only those two animals were captured. They were taken to Broms’s estate near Boden in northern Sweden.

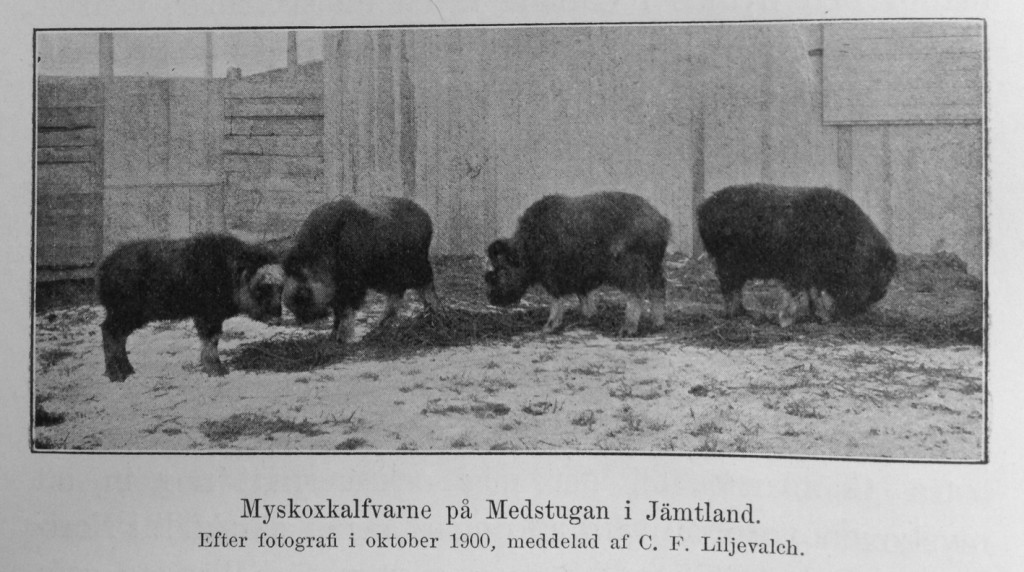

Nathorst was disappointed that only two animals had been brought back, so when he heard that four calves had been captured by a Norwegian and were for sale in Tromsø, he asked the industrialist and active supporter of the Biological Museum Karl Fredrik Liljevalch Jr. to buy them. Liljevalch did so and brought the four calves – two male and two females – to his estate Medstugan in Jämtland. One of the males died soon afterward from a pelvic injury sustained either during capture or transport.

Although Nathorst had predicted that muskox calves would be easily domesticated if around humans early on, they instead were quite unruly. According to Henrik Persson who worked for Liljevalch when the muskox were brought to Medstugan, the animals were uncooperative and one of the males was consistently charging Henrik’s father Per.

The muskox did not fare well. One of Broms’s calves soon died and the other was brought to join the Liljevach herd. They lived in a half hectare pen and were fed on Timothy-grass (used as cattle fodder), rutabaga, and carrots. By 1904, they had all died.

These animals, like the beaver I discussed previously, had an afterlife. In 1902, Liljewalch donated two complete muskox skeletons to the Swedish Museum of Natural History collection. In 1904, he donated the body of Hjalmar. The Vetenskapsakademien yearbook recorded the donation of “the muskox Hjalmar, who was brought home by the Broms-Kolthoffska expedition of 1900 and lived in Norrland until May 1904.” The scientific section recorded that they had prepared Hjalmar and the skin added to storage.

Nathorst had commented in 1900:

They [the muskox] kept not here as a curiosity, but are be domesticated, for the benefit of our descendants. One may seriously hope that the experiment will succeed.

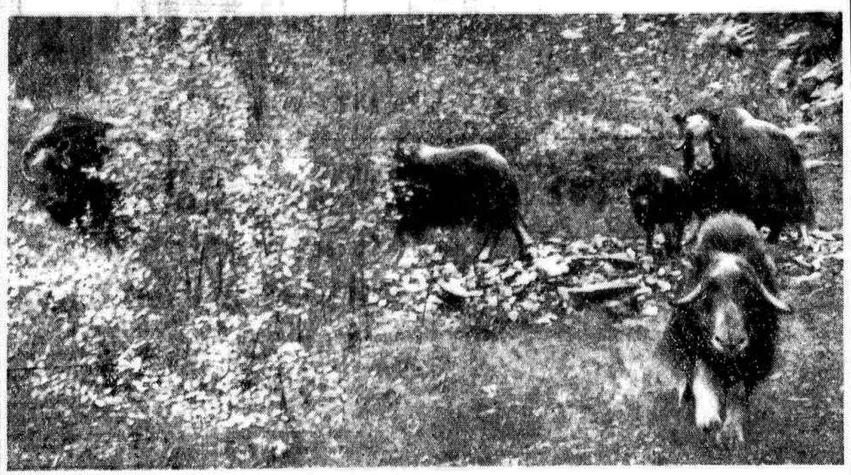

Only four years later, the Swedish domestication experiment came to an end, an utter failure. Maybe that’s why its been forgotten for the most part. The history of the Ryøya attempt to do the same thing 50 years later in Norway shows that the failure was not an isolated one. Muskox are not destined for domestication. But they may be destined to run free in Scandinavia, as they have been doing for 60+ years in the mountains of middle Norway and Sweden.

One Comment

Pingback: