Racoon dogs in the Anthropocene

The June/July 2014 issue of Filter, a Swedish magazine, features an extended 23-page article “Att jaga sin egen svans” about the arrival of raccoon dogs (called mårdhund in Swedish) in the country and the attempts to stop it from spreading. I had the pleasure of being interviewed for the article by the journalist Madelene Engstrand Andersson–my first interview completely in Swedish.

The article discusses the Swedish program to eradicate raccoon dogs before they become permanently established in Sweden. Raccoon dogs (Nyctereutes procyonoides), a member of the Canidae family which also contains our pet dogs, are from East Asia. For a cultural reference, I can note that the rebellion group in the Japanese movie Pom Poko are raccoon dogs (tanuki). They were imported to Russia in 1929 for fur farming and some got loose. When they moved into Finland, they rapidly expanded. In 1970, 800 raccoon dogs were killed; in 2011, almost 180,000 were killed!

As you can imagine, Swedish conservation and hunting groups have been worried about the eventual spread of the animal into Sweden. The first reproductive pair were observed in along the Swedish-Finnish border in 2006. The objections to the raccoon dog have been both that it is a threat to biodiversity and it is a disease carrier (rabies and dog tapeworm). The official position of the Swedish EPA is that raccoon dogs must be stopped from spreading in Sweden. This has meant in practice hunting and trapping of the animals, including many found by catching one animal, radio tagging it, and then tracking it back to the larger group. A network of wildlife cameras has been used to track animals crossing into Sweden. Interestingly, although disease always comes up as a concern, the veterinary testing of captured and killed animals during the EU-funded “Management of the invasive Raccoon Dog (Nyctereutes procyonoides) in the north-European countries” project (2010-2013) has never found one infected with rabies or tapeworm.

When the journalist called to talk about this, I spoke about ‘belonging’ and how humans determine whether or not an animal should be considered native. I spoke about the muskox in this regard–that there has been a debate in Sweden about whether or not the reintroduced population really ‘belongs’ to the Swedish fauna. I also wanted to stress that national boundaries don’t matter to an animal or a group of animals. Those are purely human societal boundaries. Here’s a short translation of that section of the article:

We can also think about what is actually native (inhemskt) and what is foreign (utländskt). Animals and plants don’t care about national boundaries.

“The only thing animals do is look for a place where they can live well,” says Dolly Jørgensen. “They want to have good food, a good place for their offspring to grow up at. So should people have the right to decide if they have the right to come here or not? This is to a high degree an Anthropocene question. We move animals around and think we have control, but we don’t.”

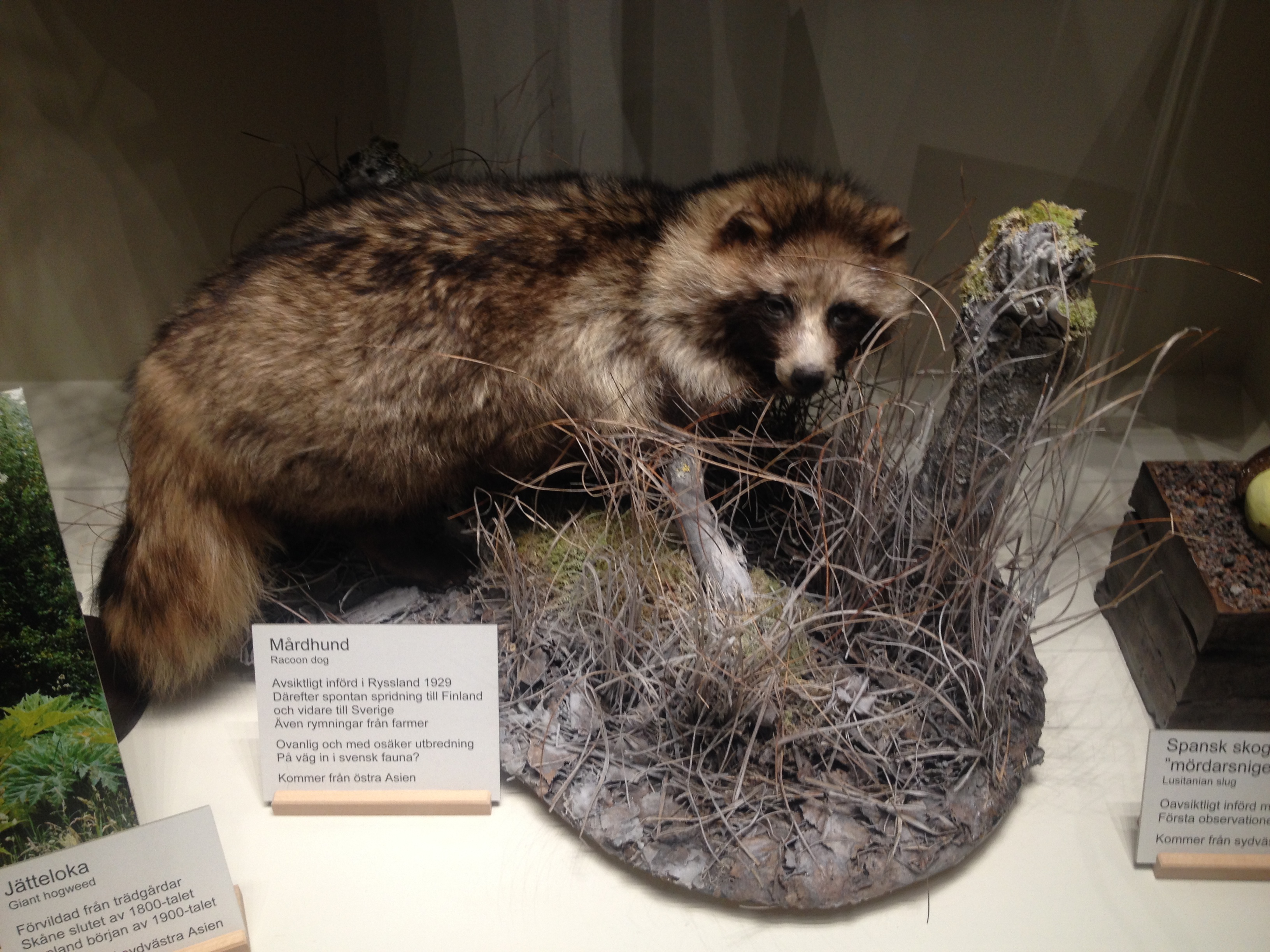

Should we say that if the raccoon dog arrives here on its own, it belongs? I recently saw a display at the Naturhistorisk riksmusset in Stockholm of Sweden’s ‘New species’ (Nya arter) including the Canada goose, the brown rat, and the map butterfly. The point of this case within the Swedish fauna room was to bring up species whose ‘belonging’ status is being questioned. The raccoon dog and its history was featured in the case with the question ‘On its way into the Swedish fauna?’ This indeed is the question.

It seems to me that the Swedish nature protection and hunting groups decided that the raccoon dog is threat to biodiversity (whatever that means) even before studies of the actual ecological effects of raccoon dogs in Sweden are known. The justification of the raccoon dog culling in the EU Life project report is that even though raccoon dogs are not doing damage now, they will if we don’t control them.

I don’t doubt that there will be effects if raccoon dogs spread in Sweden, but I wonder if we have the right to judge those effects. Don’t raccoon dogs as a species have the right to succeed and spread just like humans? In the Anthropocene, who are we to harshly judge the survivors?

3 Comments

Stim

I’m not sure why you wonder what “threat to biodiversity” means. The simple, widely accepted lay definition is perfectly adequate: the decline, often to extirpation, even extinction, of native species. Among the top drivers of the decline is non-native species which prey upon, compete with, disturb the habitat of, and/or hybridize with native species.

I’m also puzzled by your seeming belief that controlling raccoon dogs is an excessive human intervention into the world of animals supposedly beyond our control. Raccoon dogs only exist in Europe because of human decisions. We introduced them from Asia. That human decision is now harming native species. That is our fault, not the raccoon dog’s. We have to take responsibility for that decision and determine if we are going to allow the harm to continue or not. It makes no sense to assert that controlling raccoon dogs is an intervention but ignore that introducing them was itself an intervention.

Finally it is fatuous to argue that since species move around on their own, colonizing new areas, that there is no important distinction to be made between native and exotic species or between natural and anthropogenic colonization. The difference, as abundantly described and research in conservation biology literature, is time. Natural colonization is slow. This gives the pre-existing species long periods of time to adjust to and evolve around the new arrivals. The ecosystems change slowly via the process. The net result is a low extinction rate and low ecosystem disturbance due to natural species colonization. The human movement of species such as the raccoon dog has vastly accelerated the rate of change. It is now occurring so fast and so systematically, the pre-existing species have no time to adjust and evolve. Indeed, there is no consistent new condition to evolve around, because the introduction of new species is not episodic, it is constant. Only broad generalists like geese, coyotes, sparrows, etc. can adapt to a relentlessly changing environment. The rest decline, many to extinction.

Consider this exact–indeed, highly connected–parallel: species have always gone extinct, it is natural. Humans are driving species, so that is natural too. There is no difference. This is true, but only in the meaningless sense that everything, including rape, murder, war and torture are “natural.” Virtually everyone agrees that it is critical to recognize that the anthropogenic extinctions differ from natural extinctions because of time. They are happening at a vastly more rapid rate and are not episodic, they are relentless

There are many legitimate questions to be asked about the difference between exotic and invasive species, about which exotics are harmful and why, about which can and can’t be controlled and at what cost. To pretend, however, that there is no important distinction between natural and anthropogenic species spread, is not credible.

dolly

Thanks for the comment, Stim. I think that the definitions are much less clear than you put it here. Your definition of “threat to biodiversity” is built upon ‘native’ and ‘non-native’ species — but I would argue that this project (as you can read elsewhere on this blog) is showing how contested, unclear, historically-constructed, and anthropocentric those ideas are.

I am, of course, not saying we should be unconcerned about species extinction and human involvement in ecosystem change. But I want to challenge us to think about how we judge ‘belongingness’ in the Anthropocene.

Stim

We’re in the midst of the sixth greatest extinction crisis in 4.5 billion year history of the Earth. Species are suffering and going extinct at an unprecedented because of our actions. One of those actions is moving species around the globe against their will at a rate never seen before in nature. While every one of these species is not harmful, enough are to cause massive ecosystem disruption and extinction. That’s our doing, not the introduced animals. They would not have crossed the Atlantic on their own and didn’t ask us to carry them. In many cases they were moved in order to commercially exploit them (pigs) or to serve other human purposes (tamarisk trees).

It is not biocentric to pretend they are naturally present. It is not egocentric to stand by and watch other species decline and go extinct under pressure from the species we chose to drop on top of them. And it is certainly not anthropocentric to pay attention to the damage we wrought and reverse it where possible (often it is not with invasive species).

The anthropocentric position, it seems to me is to say, we brought them here, we caused and are causing the extinction of native species, but we’re going to keep doing it because other species matter less or not at all compared to those we humans have selected to inherit the earth.

Going back to Buffon who was perhaps the first to understand the massive impact of human redistribution of species, the anthropocentrists have hailed the change as part of the rightful, natural ascendency of humans. They still do today. Countering the reordering if the planet, respecting the species that evolved in each region at whatever scale they themselves evolved is a critical part of biocentrism.