Environmental relationships in the Laudato Si´encyclical

Pope Francis published his much anticipated encyclical on the environment, Laudato Si´, last week. Whether or not you are Catholic (I am not), you should read the document because it is an important contemporary statement about the past/present/possible future relationship between humans and the Earth. Although much of the press hype has portrayed the document as a position on climate change, if you take time to read the whole 180 page document (in English), you realise that it is much more an environmental justice manifesto concerned about the intertwined fates of humans and non-humans. As an environmental historian working on extinction, conservation biology, and ideas of belonging, I read the encyclical with an eye toward the kind of environmental relationships it depicts. I have four major observations.

First, I was struck by Francis’s definition of environment:

When we speak of the “environment”, what we really mean is a relationship existing between nature and the society which lives in it. Nature cannot be regarded as something separate from ourselves or as a mere setting in which we live. We are part of nature, included in it and thus in constant interaction with it. (§139)

This is very similar to the way that I and Sverker Sörlin delineated the difference between environment and nature in our introduction to Northscapes, which in turn built upon his work with Paul Warde in Nature’s End. Environment is the entanglement of nature and people, thus when we do environmental history, we have to examine interactions. This entanglement is the foundation of the Pope’s insistence that environmental protection must be coupled to social betterment:

Recognizing the reasons why a given area is polluted requires a study of the workings of society, its economy, its behaviour patterns, and the ways it grasps reality. … We are faced not with two separate crises, one environmental and the other social, but rather with one complex crisis which is both social and environmental. Strategies for a solution demand an integrated approach to combating poverty, restoring dignity to the excluded, and at the same time protecting nature. (§139)

As an environmental historian, I think this emphasis on the coupling of socio-natural systems is critical. In my recent lecture for the Swedish title of docent, I said that environment exists at the centre of a triangle with nature, technology, and social systems on the sides. It is the interaction of all three that makes the thing we know as environment. Because of the connections between humans and nature, the Pope calls for “integral ecology” that combines environment, economic, and social elements (see Chapter 4), a call that I think many environmental humanities scholars would agree with.

Second, Francis has something to say about history and belongingness. He advocates the “need to incorporate the history, culture and architecture of each place” because ecology for him is “the cultural treasures of humanity in the broadest sense”. Culture is both what “we have inherited from the past” and “a living, dynamic and participatory present reality” that affects environmental relationships (§143).

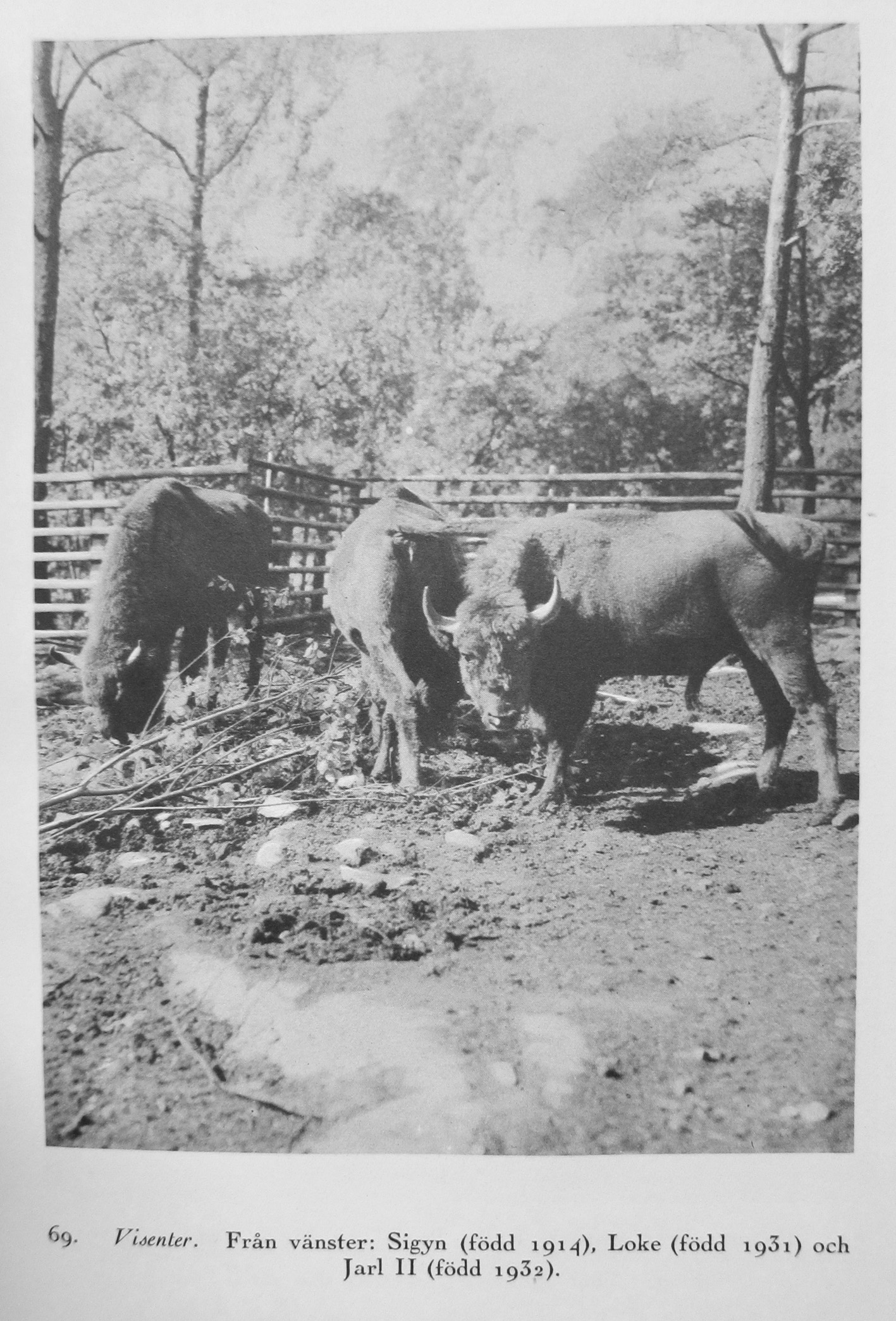

As I have written before, thinking historically is critically important for understanding today, especially since sometimes we need reminding about things we have forgotten. History and culture have environmental implications. To understand why some people say the muskox belongs in Norway or Sweden and others say it doesn’t requires historical cultural analysis. To understand why the raccoon dog is hunted down in Sweden has as much to do with culture as it does nature. The same holds true for whether or not the starling is an American bird.

The subtitle of the encyclical is “on the care of our common home”, which is also a statement of belonging. Humans and non-humans belong on the Earth, sharing this home which Francis warns has become sick and “cries out to us” (§2). The Pope is using the sense of belongingness to position his encyclical within a framework of environmental care.

Third, the Pope writes a fair amount on species extinction. He notes that many extinctions take place unknown to us, yet humans are to blame:

Each year sees the disappearance of thousands of plant and animal species which we will never know, which our children will never see, because they have been lost for ever. The great majority become extinct for reasons related to human activity. Because of us, thousands of species will no longer give glory to God by their very existence, nor convey their message to us. We have no such right. (§33)

There is certainly an extinction ethics in Laudato Si’. In the passage above, there is an assignment of blame and a judgement of right/wrong at work in extinction.

According to the encyclical, all creatures, whether they are megafauna or microfauna have value (§34), and that value is defined intrinsically rather than only anthropocentrically by our “use” of the creature (§69). This does not mean that the Pope ignores the ecosystem service or value of biodiversity. Quite the contrary, he notes that the loss of species may result in losses of resources (food, medicine, etc) in the future, but he believes that thinking of species only as potential “resources” is not enough (§32-33).

On a practical note that speaks to the concerns of conservation biology, Francis advocates “developing programmes and strategies of protection with particular care for safeguarding species heading towards extinction” (§42). Biodiversity needs to be included in assessing the environmental impact of development, and steps taken to prevent species’ “depletion and the consequent imbalance of the ecosystem” (§35). These are calls to action about species and their potential loss.

Yet, Laudato Si’ cautions against thinking that environmental issues like species loss can be countered with technocratic, economically-dependent solutions. (As a side comment, more than anything, I think this encyclical was intended as a slap in the face of the capitalist system that favours the wealthy’s consumption over the poor and leads to environmental degradation.) Francis notes that “we seem to think that we can substitute an irreplaceable and irretrievable beauty with something which we have created ourselves” (§34). This statement could well apply to the deextinction efforts I have discussed in this project. Remaking a thing is never the same as the thing.

Finally, I want to note that Francis makes a statement that environmental humanities scholars need to latch onto and make our own:

We urgently need a humanism capable of bringing together the different fields of knowledge, including economics, in the service of a more integral and integrating vision. Today, the analysis of environmental problems cannot be separated from the analysis of human, family, work-related and urban contexts, nor from how individuals relate to themselves, which leads in turn to how they relate to others and to the environment. There is an interrelation between ecosystems and between the various spheres of social interaction, demonstrating yet again that “the whole is greater than the part”. (§141)

Those of us in environmental humanities fields have said and known this for a long time, but this kind of statement can help us as researchers to address the oft-dreaded ‘relevance’ question in our research proposals, interaction with the public, and making our findings count in politics.

While people may not agree with everything in Laudato Si´, as environmental historian I found it refreshing to have a major religious/political figure speaking out against the historical lack of political will to conserve resources and the modernist turn toward technological solutions to environmental problems, advocating a humanities-based approach to environmental issues, and pointing out the need to have all of us (regardless of religious beliefs) embrace our common home.

One Comment

Tina Adcock

Thank you for this terrific post, Dolly. As environmental historians/humanists, we should all read Laudato Si’, but I fear, in practice, few of us will make or take the time to do so. So I’m glad that you’ve read it, and have given us the benefit of your thoughts.